1979 KIM-1, AIM 5 and 6502 articles. German, scanned by Matthias, SBC at VzEkC e. V. forum

About small SBC systems

1979 KIM-1, AIM 5 and 6502 articles. German, scanned by Matthias, SBC at VzEkC e. V. forum

Labu Asabu made 5 units of the AIM65-CPLD-3V3 for sale.

The price is 55,000 yen for a full set + accessories.

Shipping costs will be charged. Overseas customers will be charged customs duties for imports.

Email to info@labo-asabu.com

Filippo (shinymetal6) published an alpha version of aim65_quartus, an FPGA clone on his github resource.

Forum discussion on the MisTer forum here.

Here the readme of aim65_quartus by Filippo:

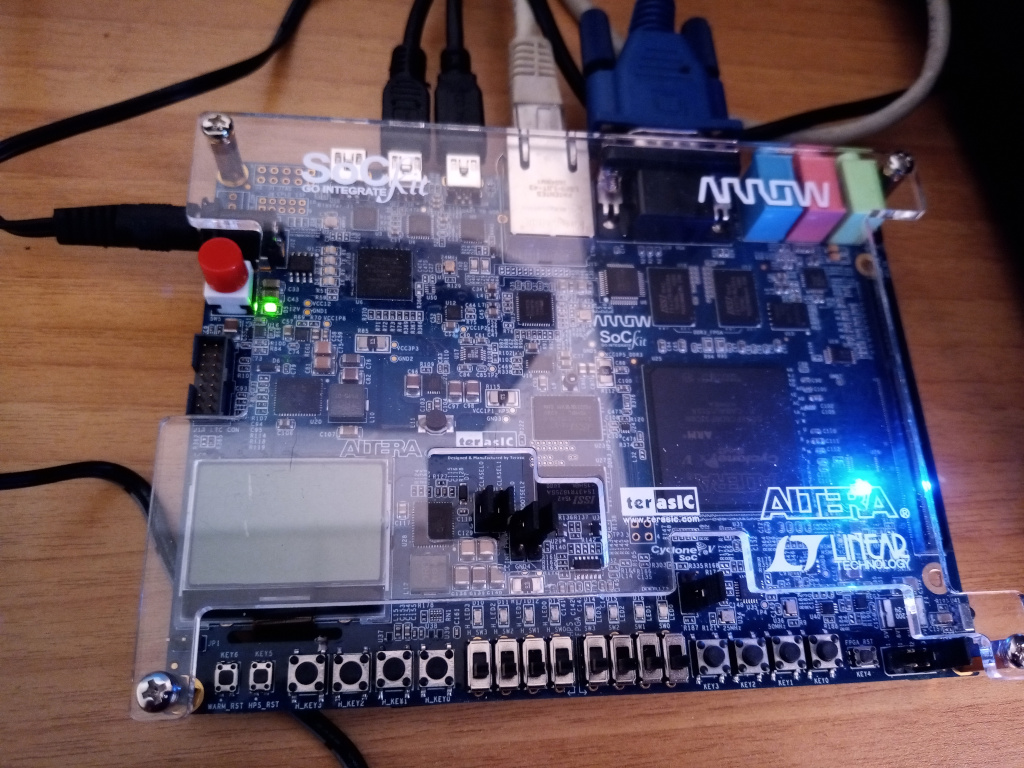

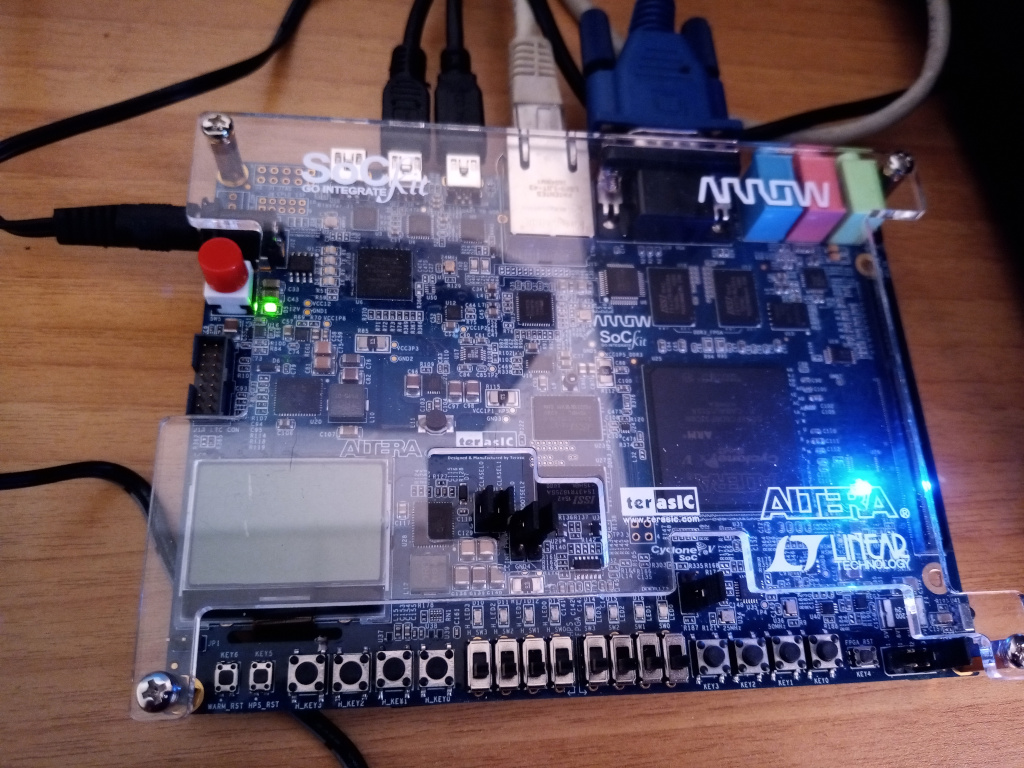

This is an alpha release of a verilog Rockwell AIM65 in an Intel FPGA using the SocKIT board.

The Arrow SocKIT board is a nearly compatible TerASIC DE0 board where MiSTer runs.

This is a MiSTer port on the Arrow SocKIT, and as I have a SocKIT board I used their templates from MiSTer SocKIT FPGA page.

Behind the templates, the structures seem to me very similar, so probably a port on the MiSTer board should be relatively easy, but I don’t have such board.

Basically the aim65_quartus runs like an AIM65 at 1 MHz, has 32KBytes of ram ( who had so much ram ? not me for sure ! ) and excluding printer and tape all the peripherals are in place and runs.

The ROMs come from Hans Hotten funtastic pages, like all the other information I found there.

The 6502 core is the Arlet one, or the Hoglet67 65C02 version based on the Arlet core. This can be selected recompiling the code

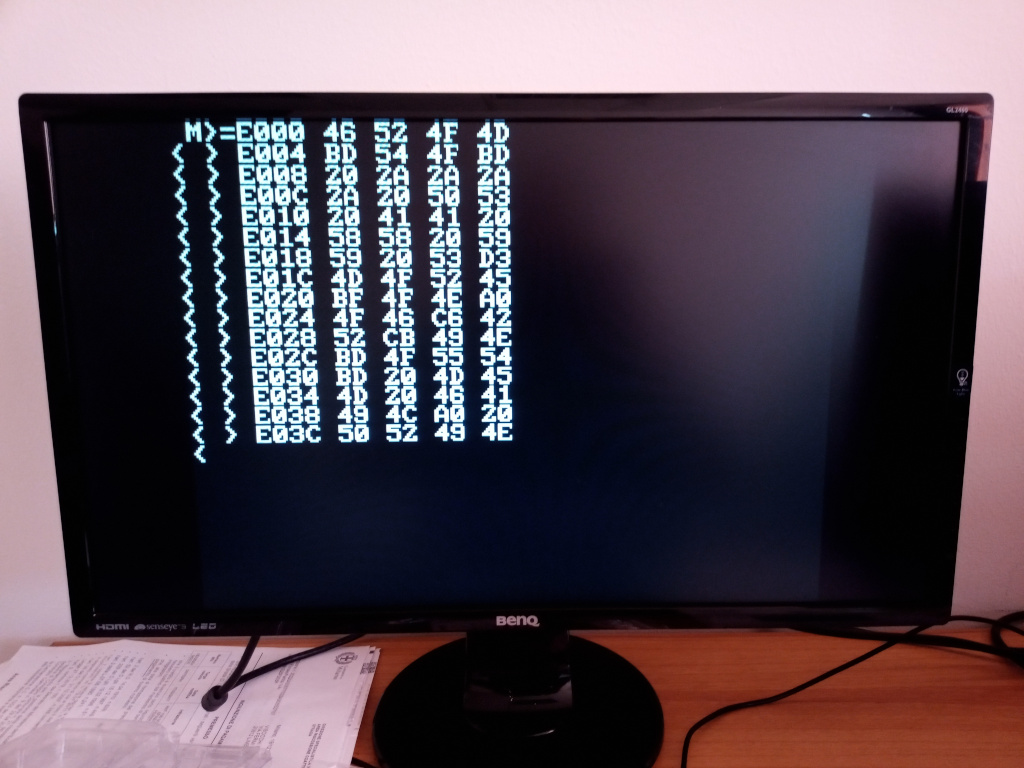

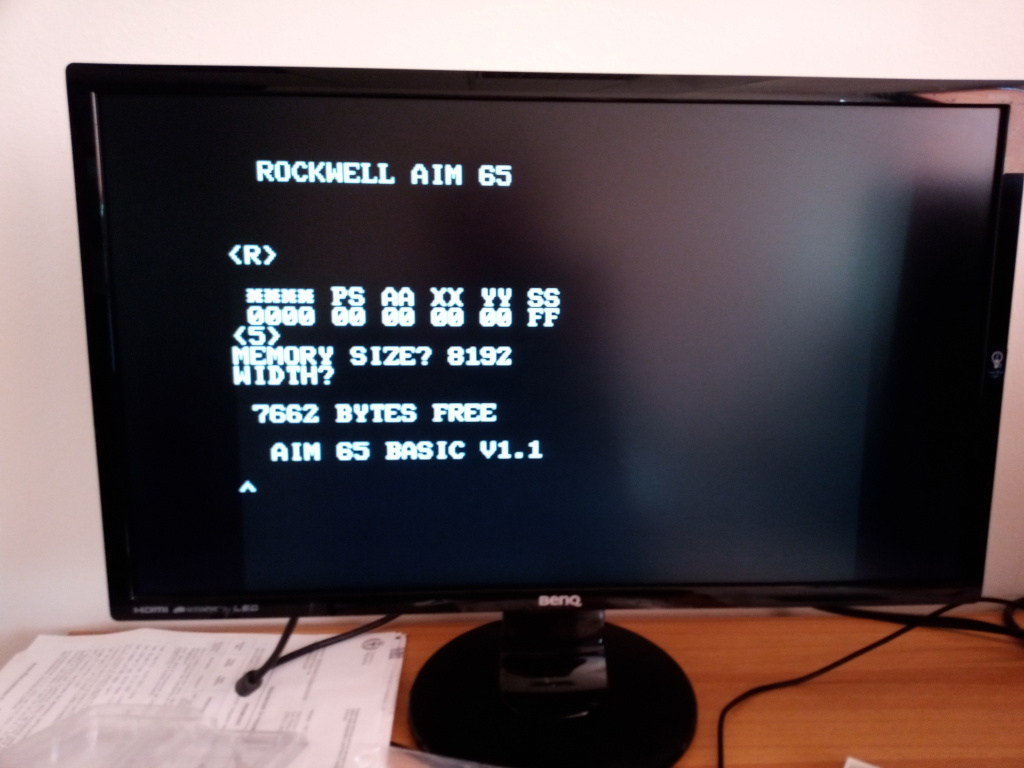

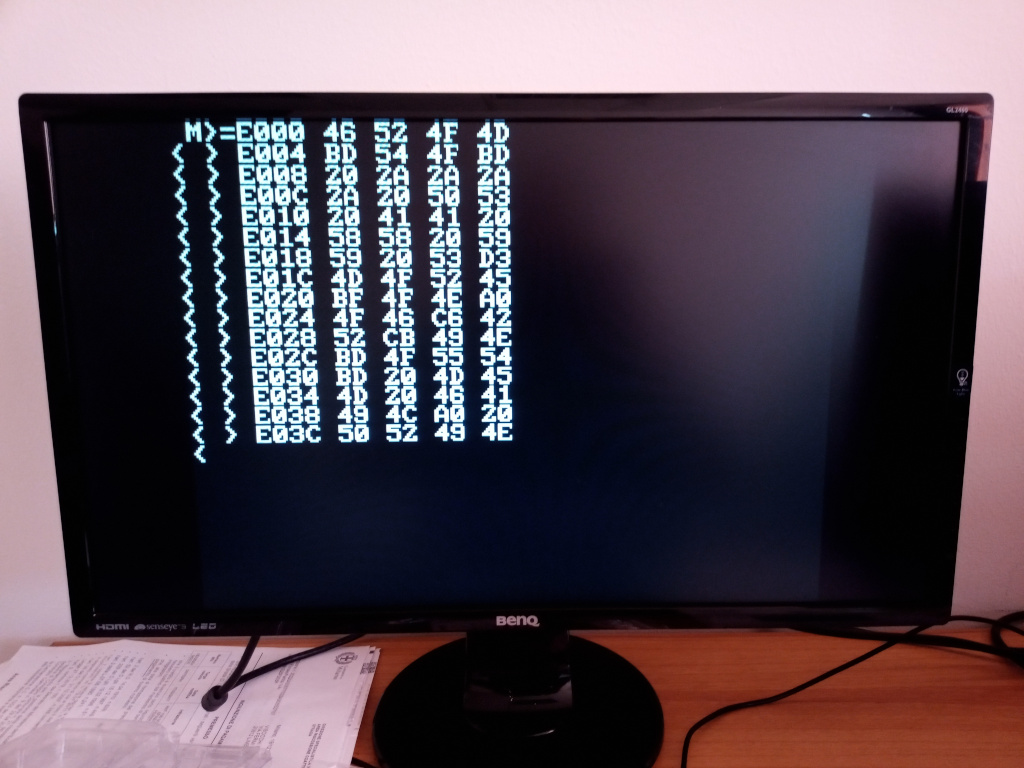

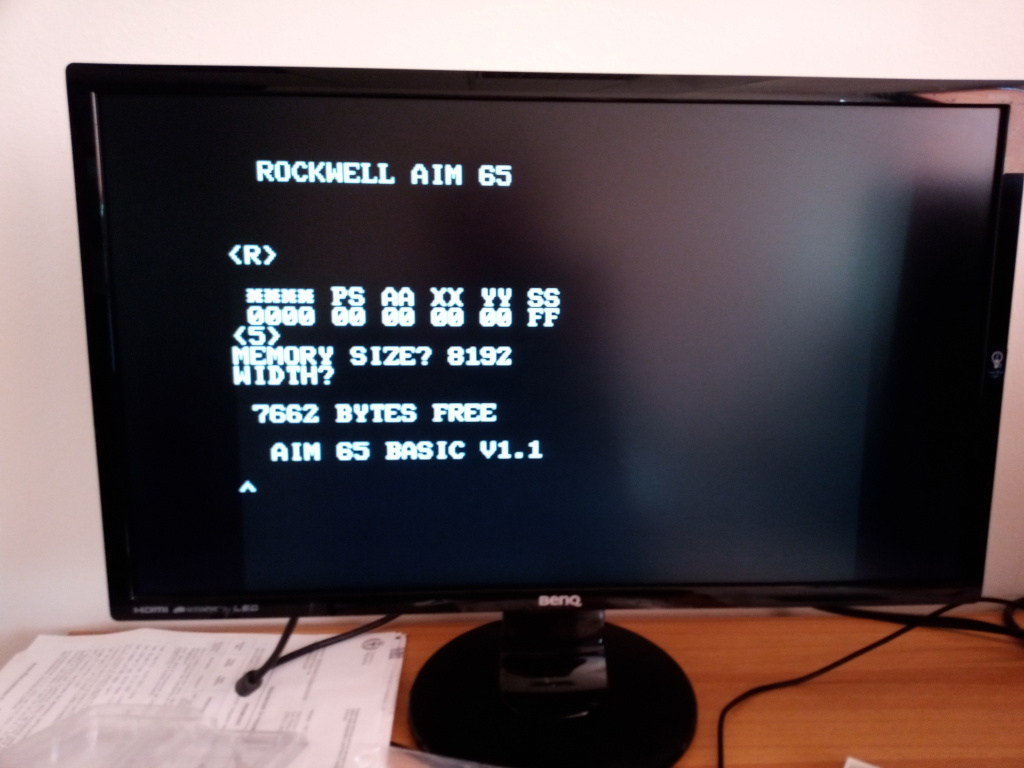

The 20 AIM65 alphanumeric displays are routed to a simple video output, some ( quite bad I know ) pictures below.

The MiSTer menu can be used to have the expansion rom with basic, forth and pl/65, again some pictures below

Still with the MiSTer menu the serial port can be enabled, the characters color can be changed and the video can run at full screen

As an additional and in my opinion useful add on, I have implemented a clear screen pressing F4, currently not used on real AIM65.

This too needs a bit of fixing here and there, but when time will leave me to work on it again I will try to fix it

Filippo (shinymetal6) published an alpha version of aim65_quartus, an FPGA clone on his github resource.

Forum discussion on the MisTer forum here.

Here the readme of aim65_quartus by Filippo:

This is an alpha release of a verilog Rockwell AIM65 in an Intel FPGA using the SocKIT board.

The Arrow SocKIT board is a nearly compatible TerASIC DE0 board where MiSTer runs.

This is a MiSTer port on the Arrow SocKIT, and as I have a SocKIT board I used their templates from MiSTer SocKIT FPGA page.

Behind the templates, the structures seem to me very similar, so probably a port on the MiSTer board should be relatively easy, but I don’t have such board.

Basically the aim65_quartus runs like an AIM65 at 1 MHz, has 32KBytes of ram ( who had so much ram ? not me for sure ! ) and excluding printer and tape all the peripherals are in place and runs.

The ROMs come from Hans Hotten funtastic pages, like all the other information I found there.

The 6502 core is the Arlet one, or the Hoglet67 65C02 version based on the Arlet core. This can be selected recompiling the code

The 20 AIM65 alphanumeric displays are routed to a simple video output, some ( quite bad I know ) pictures below.

The MiSTer menu can be used to have the expansion rom with basic, forth and pl/65, again some pictures below

Still with the MiSTer menu the serial port can be enabled, the characters color can be changed and the video can run at full screen

As an additional and in my opinion useful add on, I have implemented a clear screen pressing F4, currently not used on real AIM65.

This too needs a bit of fixing here and there, but when time will leave me to work on it again I will try to fix it

An AIM 65 compatible 65C02 CPU based computer, the MC-65. With a 6532, 6522, terminal I/O, cassette interface, and in theory possible to run the original AIM 65 ROMs.

For AIM 65 ROMS and manuals, see the AIM 65 pages!

An AIM 65 compatible 65C02 CPU based computer, the MC-65. With a 6532, 6522, terminal I/O, cassette interface, and in theory possible to run the original AIM 65 ROMs.

An AIM 65 compatible 65C02 CPU based computer, the MC-65. With a 6532, 6522, terminal I/O, cassette interface, and in theory possible to run the original AIM 65 ROMs.

For AIM 65 ROMS and manuals, see the AIM 65 pages!

|

a reduced version AIM-65 Mini |

|

micro AIM-65 version 2 |

For AIM 65 ROMS and manuals, see the AIM 65 pages!

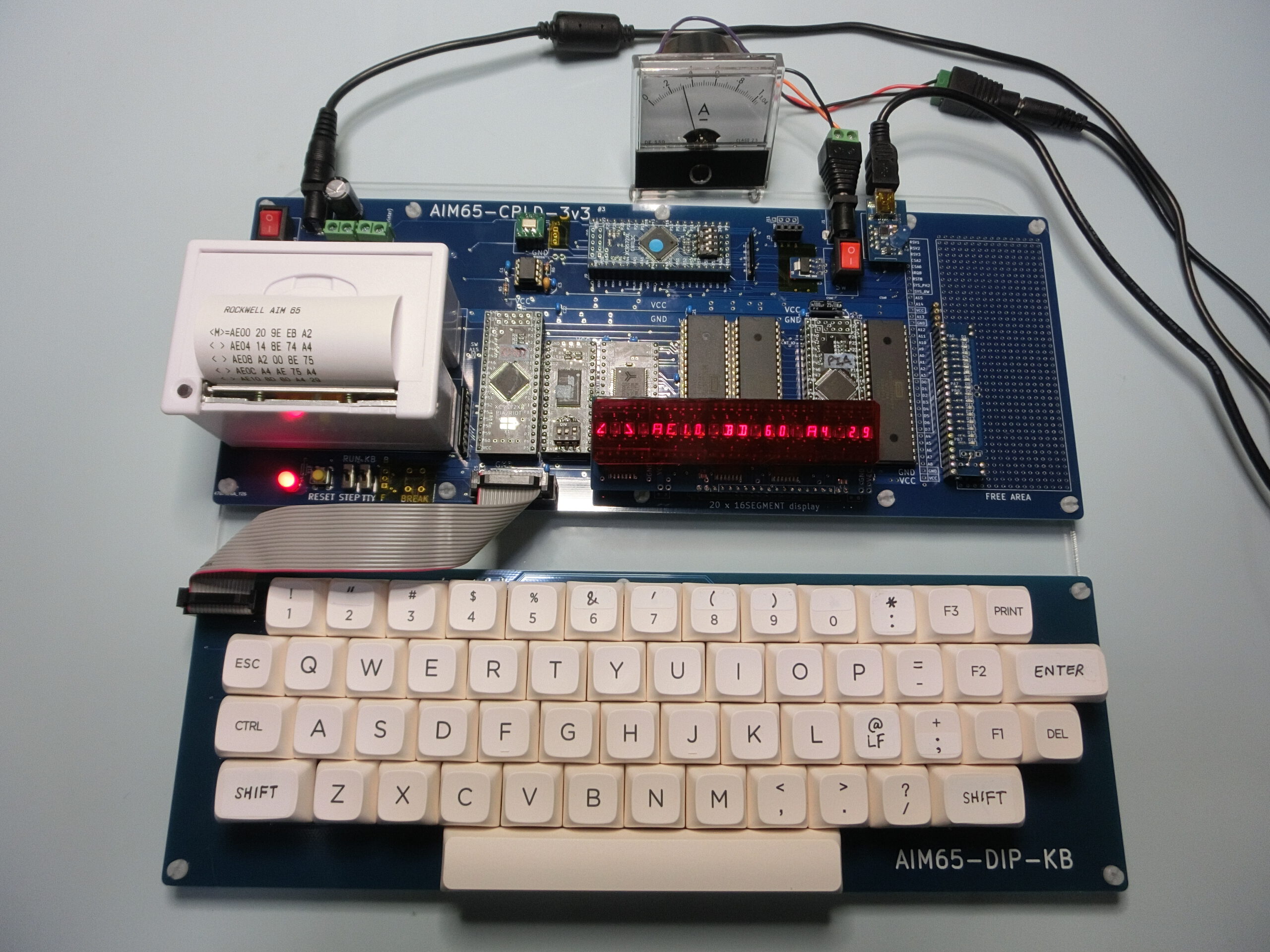

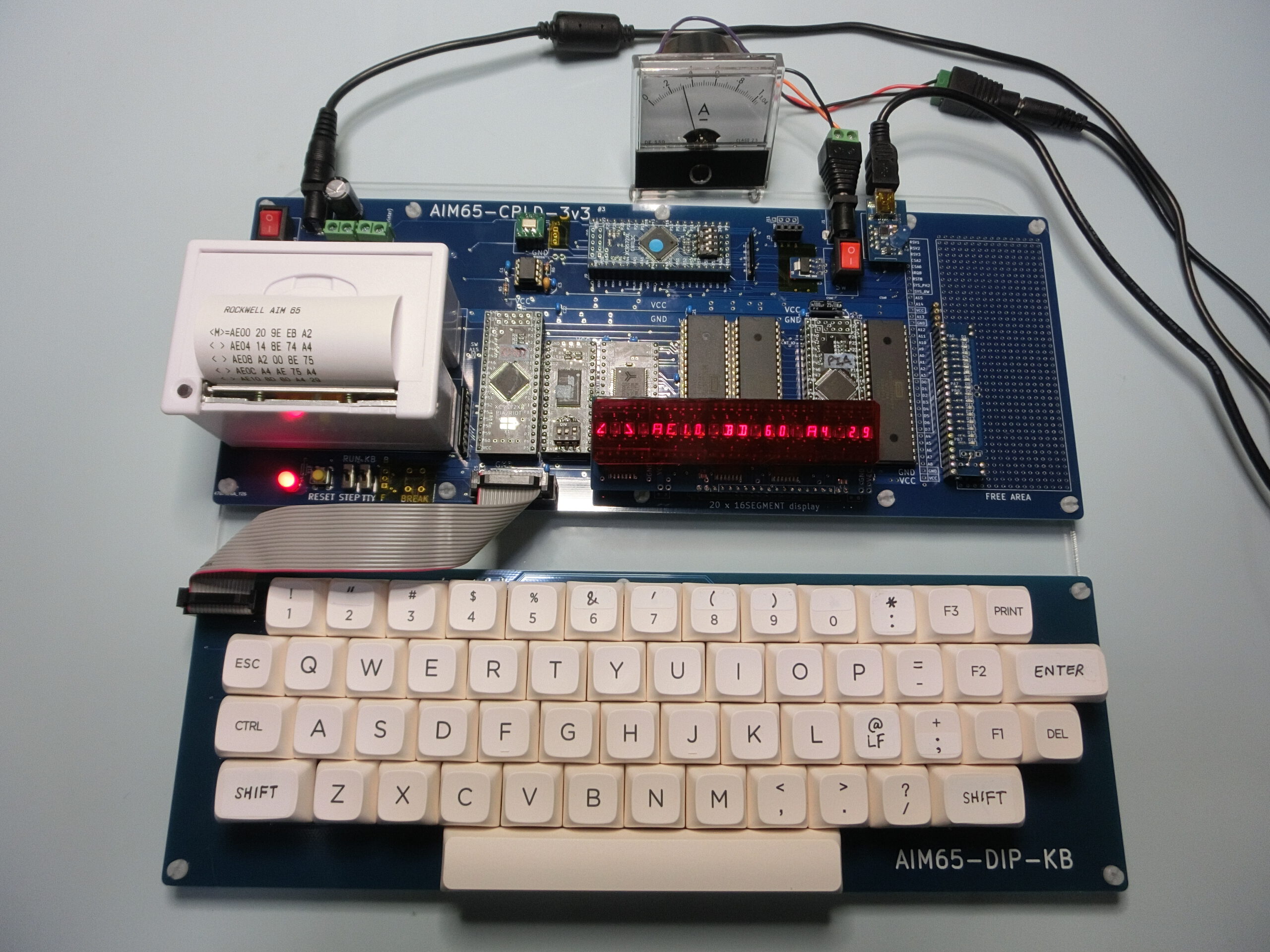

The page on the AIM 65 reproduction AIM65-CPLD-3v3 by Yasushi Nagano (Labo Asabu) has now a manual. Quite a large detailed 180+ pages one!

Working with Mr Nagano, I have translated his manual for the AIM 65 reproduction, the AIM65-CPLD-3v3, from Japanese to English. The manual is now downloadable from this page.

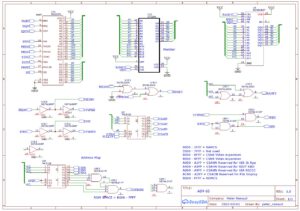

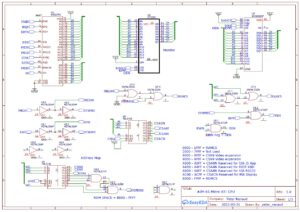

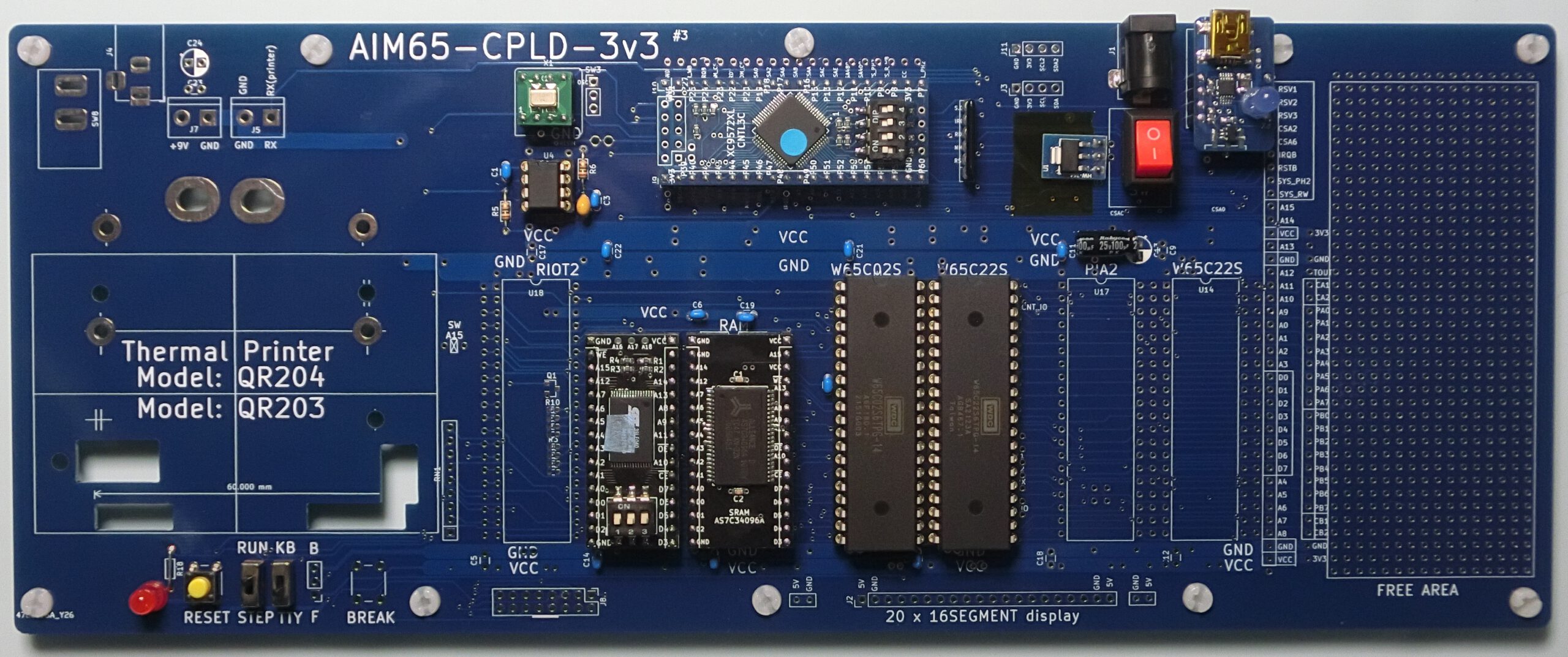

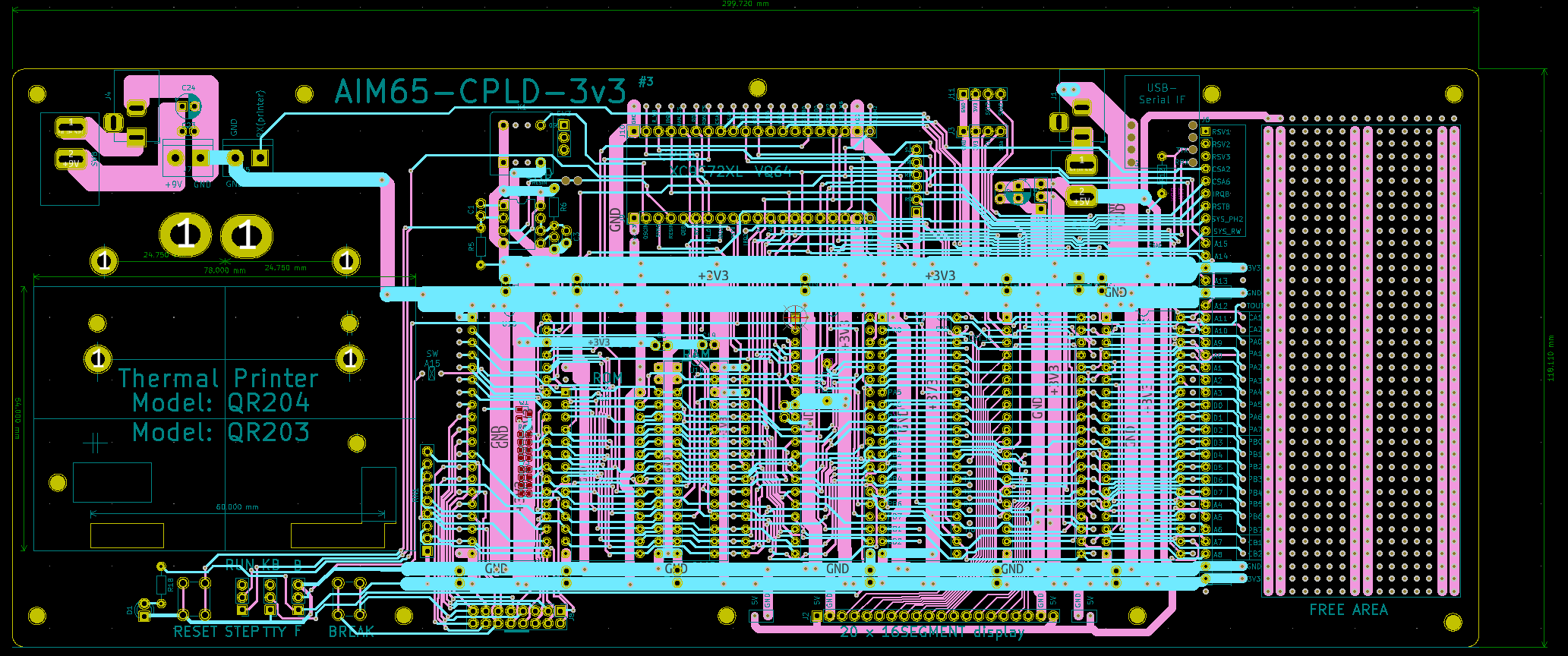

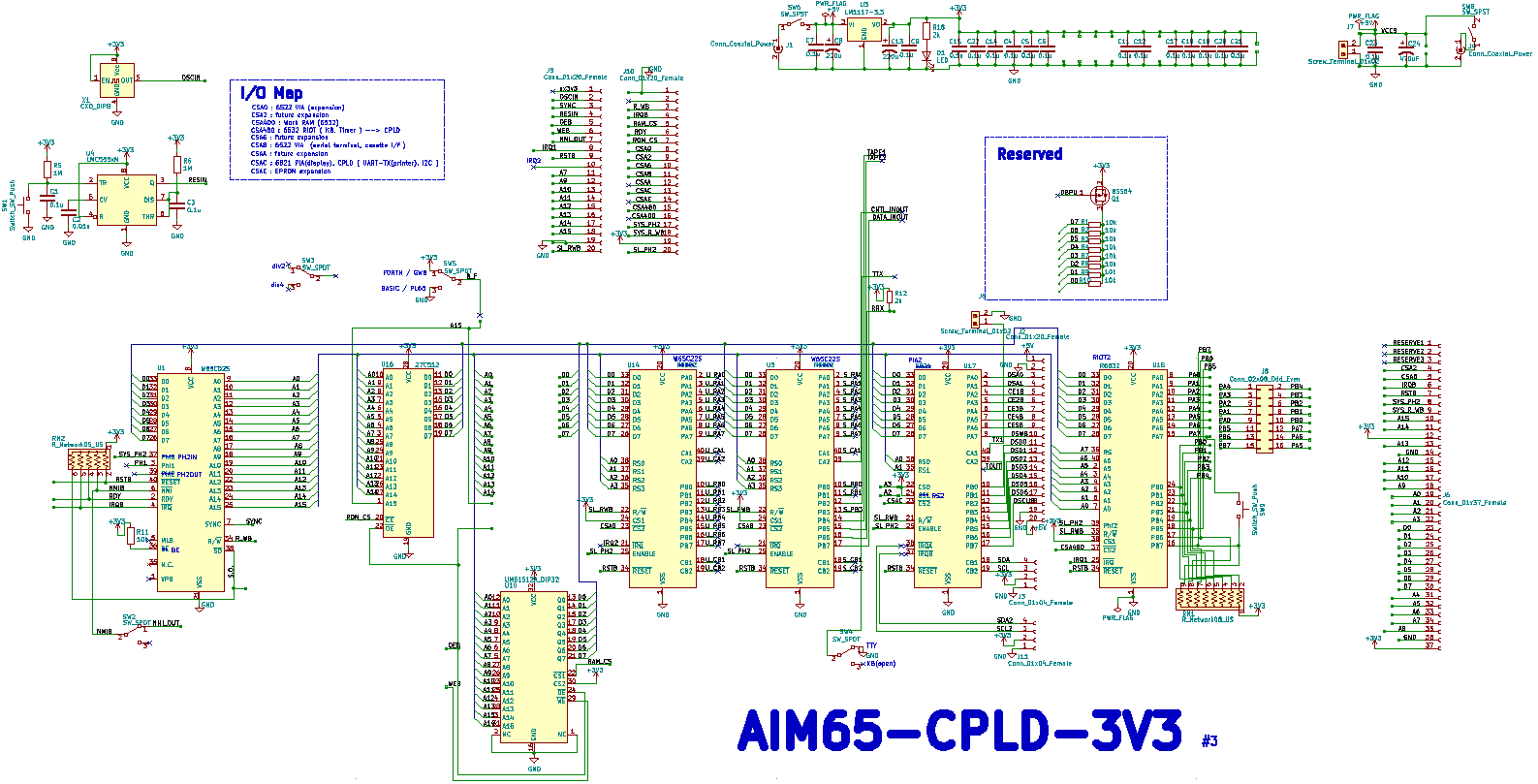

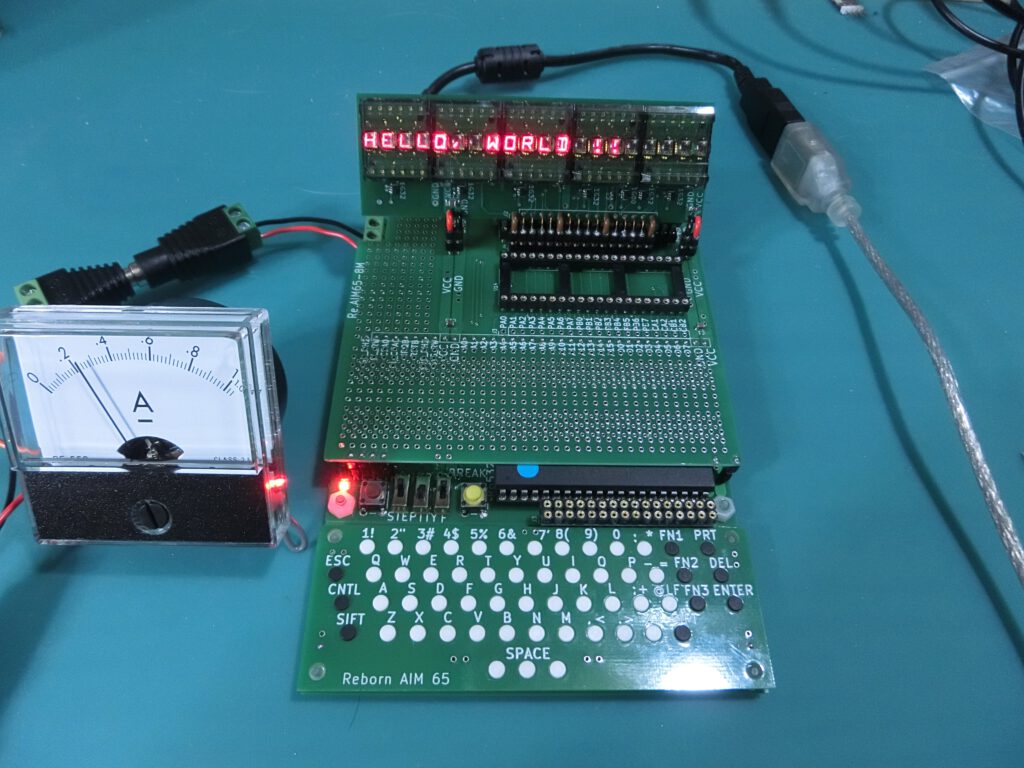

Mr. Nagano, from Tokyo, Japan send me photos and circuit diagram of an AIM 65 reproduction he designed an build: the AIM65-CPLD-3v3.

It is a beautiful, functional, and aesthetically faithful clone. In fact, he built two, one with a CPLD 3V3 version and a 5V version with a 6532 RIOT.

The AIM65-CPLD-3v3 will become available as a complete system (sold on ebay) in the near future.

Features of the AIM-65 reproduction AIM65-CPLD-3v3

Hardware

Power Supply

Clock

Software

The following can be selected by setting the DIP SWITCH of the FLASH memory board.

Manual of the AIM65-CPLD-3v3 (Version 0.3 May 2 2023)

|

AIM 65 Building a Retro-Computer manual,the AIM65-CPLD-3v3 Rev 03 |

Mr. Nagano also made a version with a voltage of 5V and running at 2MHz. R65C02, R65C22, R6532A are used for it.

Older versions:

Mr. Nagano as user Labo Asabu on Youtube

User Marco Rey y Sander has received one of the first systems, sent to developers:

Follow Mr. Nagano on twitter: Asabu Labo

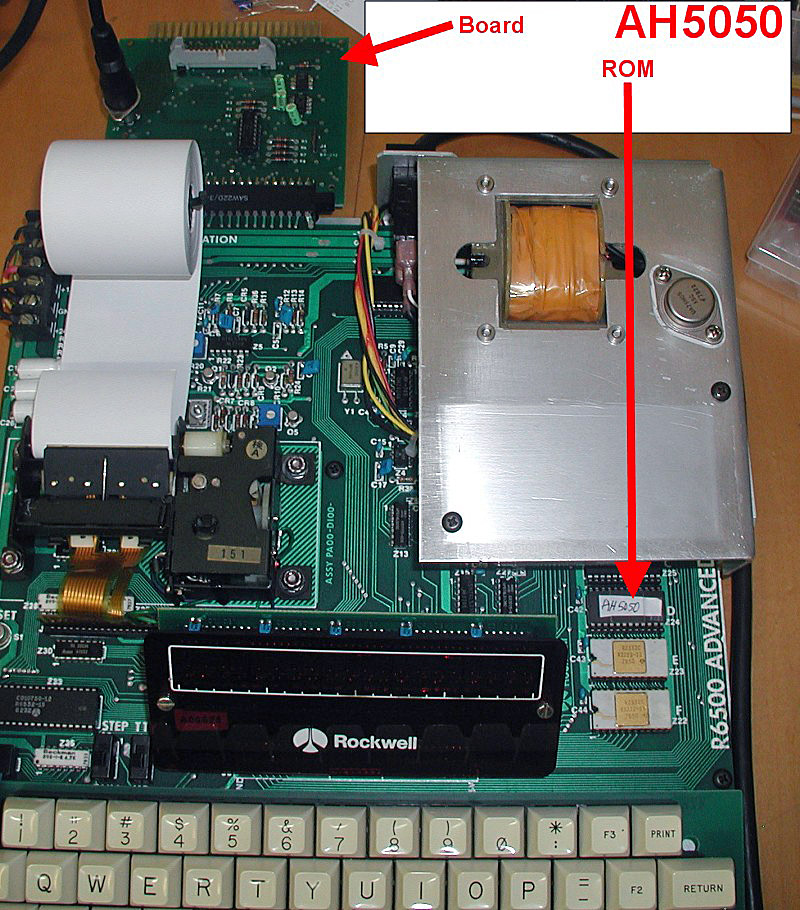

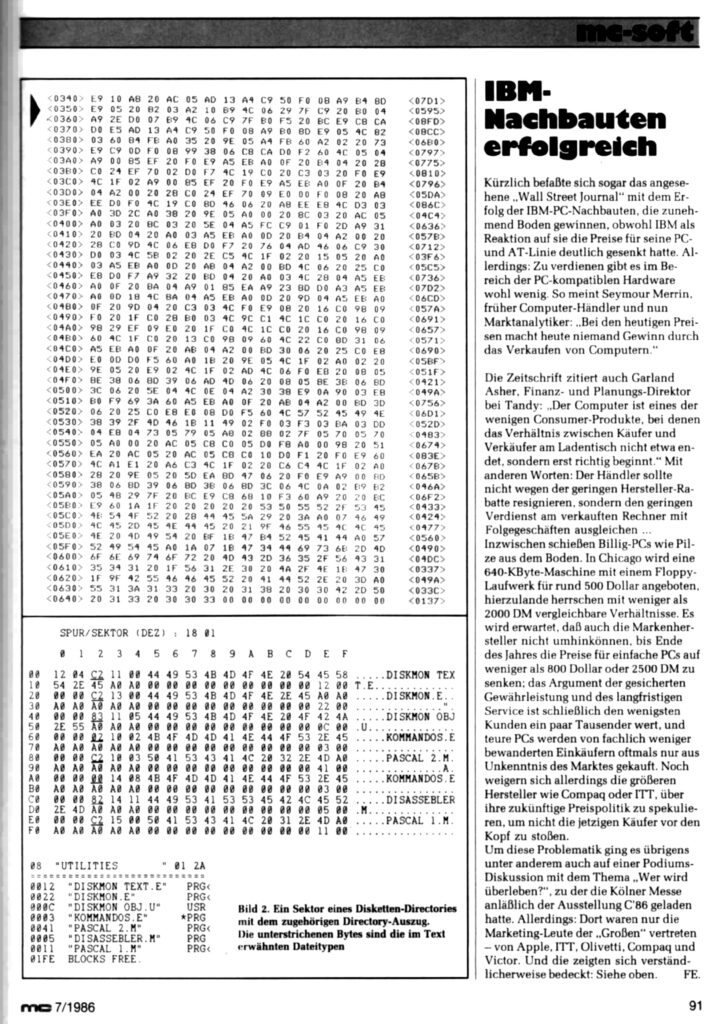

In 1983 the company ABM sold a floppy disk system, Commodore IEC 1541 based, for the AIM 65. It also offered a serial interface for the AIM 65 TTY connection and a parallel port.

The system consists of a PCB with the interfaces, a manual and the AH5050 ROM. The user has to add the Commodore diskdrive and IEC cable.

The 1541 Commodore drive was quite popular in the 80ties for SBCs, since it was affordable, the serial IEC connection simple (one 7406 TTL IC and a couple of I/O lines) and the drive itself intelligent, the host did not have to implement a DOS with low level drivers and file system. It is slow, and has a low capacity, small SBCs like the AIM 65 are more than happy with that

Nowadays floppy drives like the 1541 are like dinosaurs. But the SD2IEC 1541 replacement devices are cheap!

[