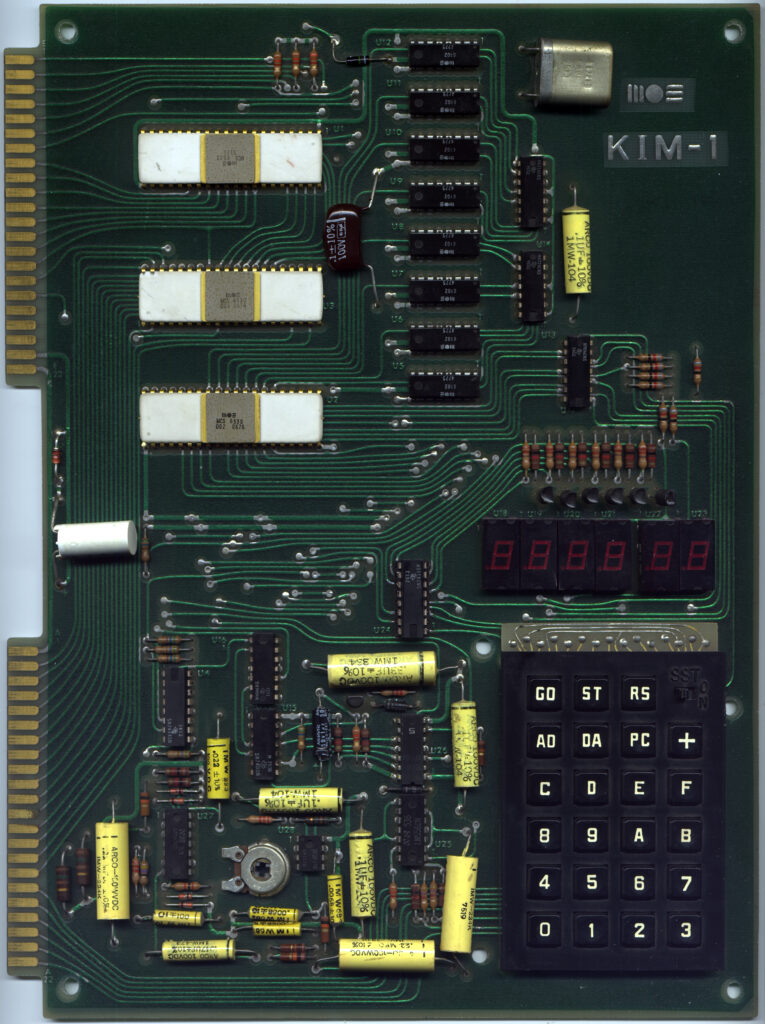

The KIM-1 went trough several revisions without any change to the specifications. The first revisions appeared as MOS Technology products, the label MOS in in the front top right corner. When Commodore took over MOS late 1976 the label (Rev D) changed to Commodore C MOS.

MOS did three versions, the unnamed first one, a Revision A and a Rev B. I have never seen a Rev C.

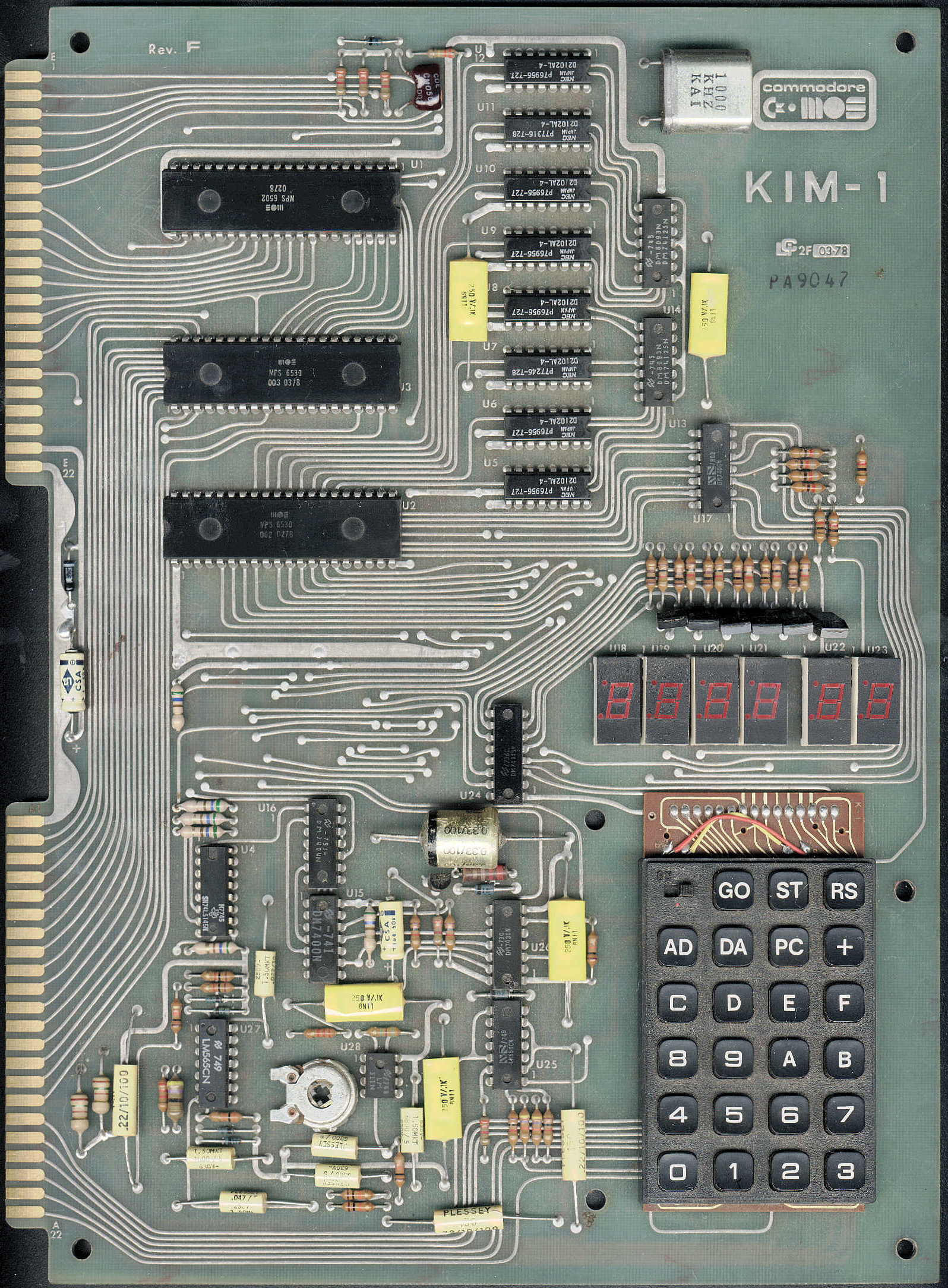

Commodore MOS did Rev D to G, starting in 1977 and well into the 80ties. Many KIM-1s were sold, first to industry and later to education and hobbyists. Nowadays KIM-1s are not rare but have become quite expensive, collectors value especially the early ones with a white 6502 IC.

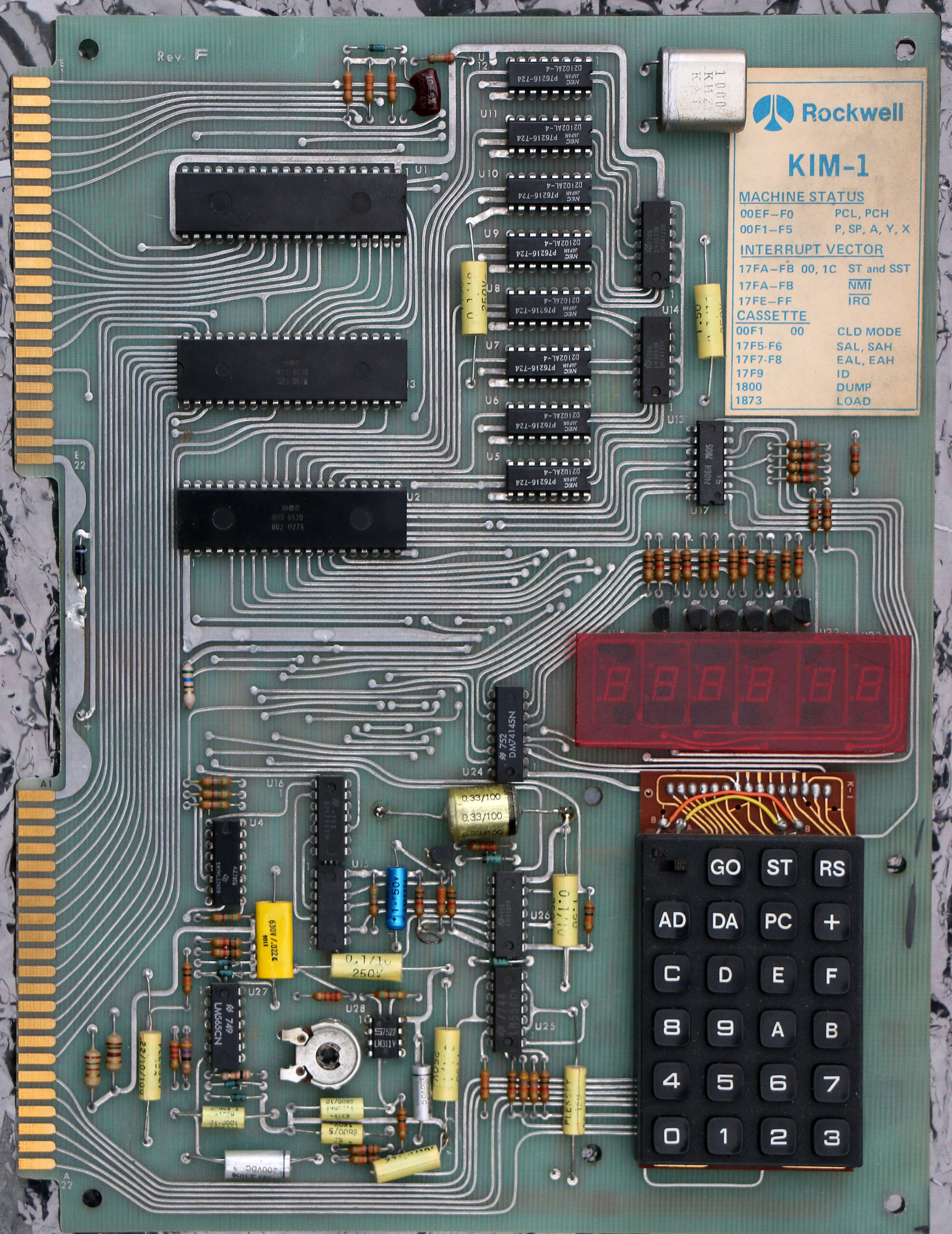

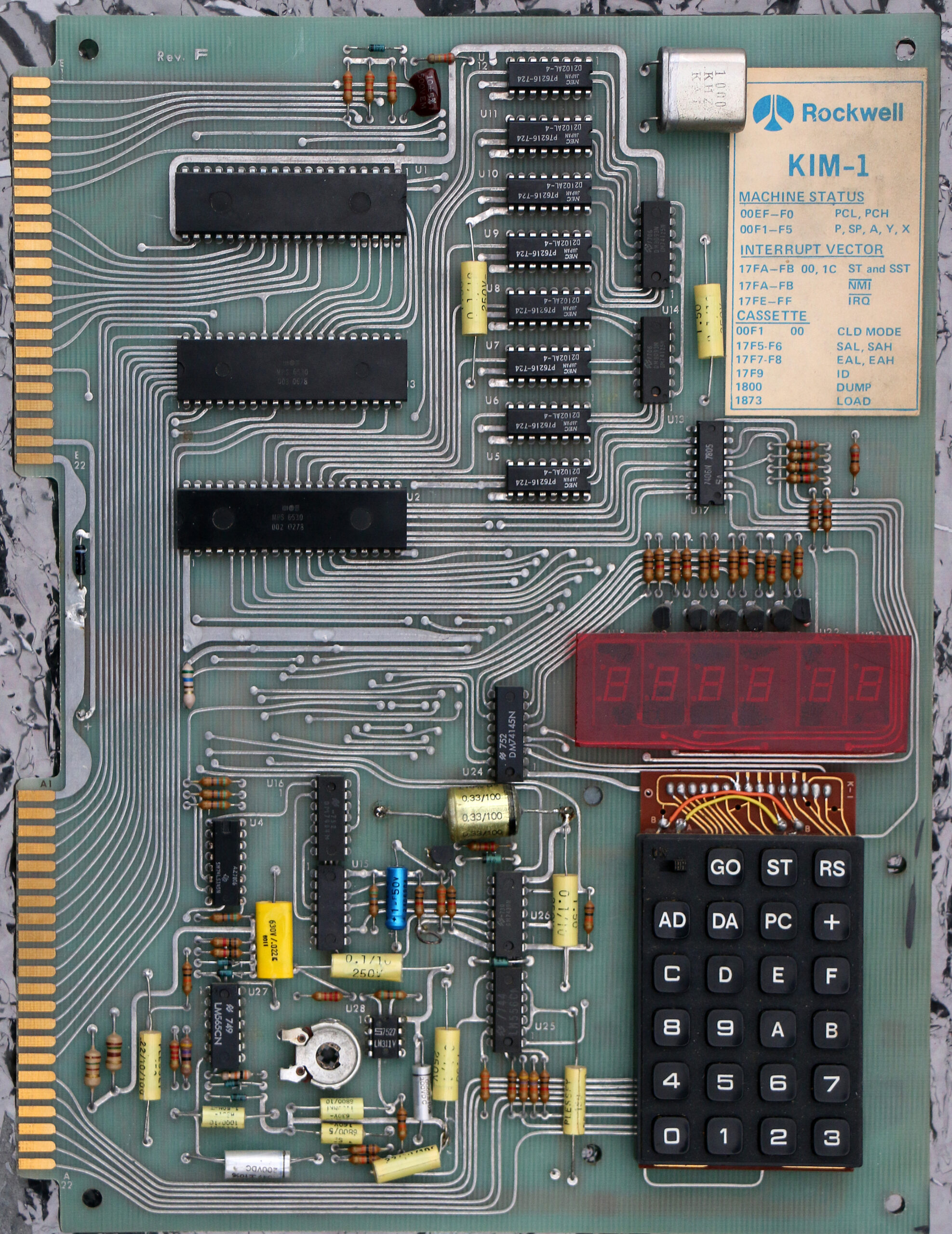

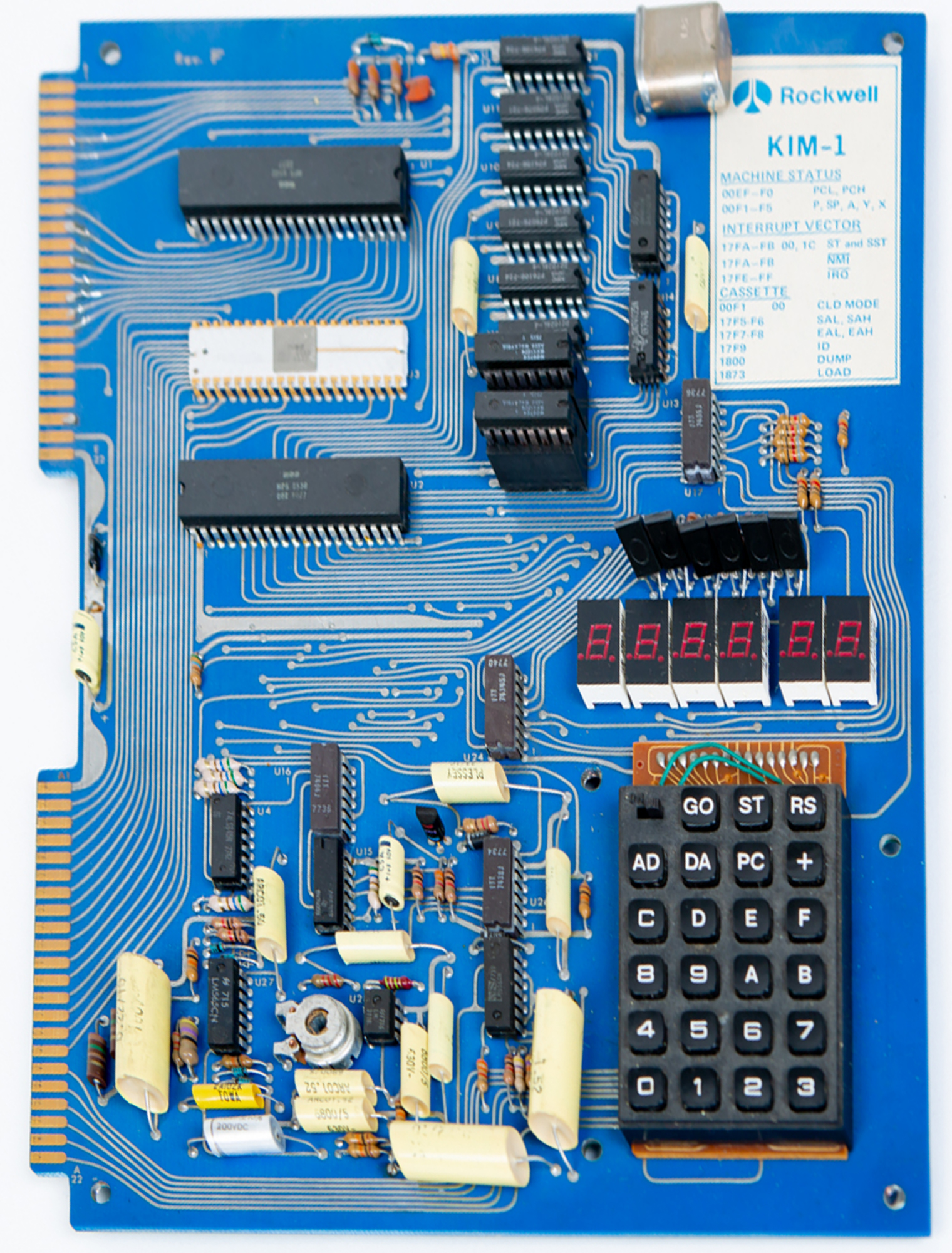

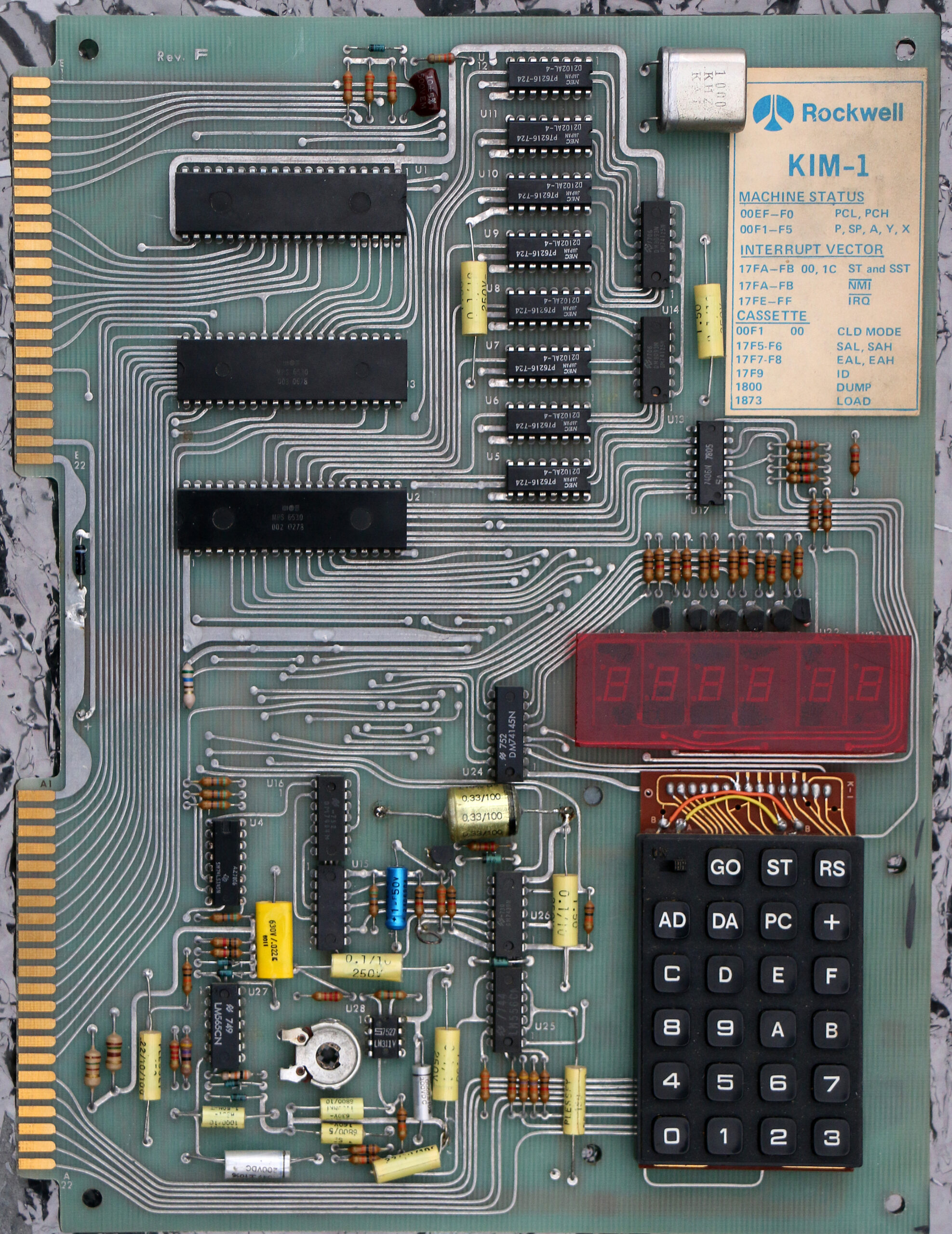

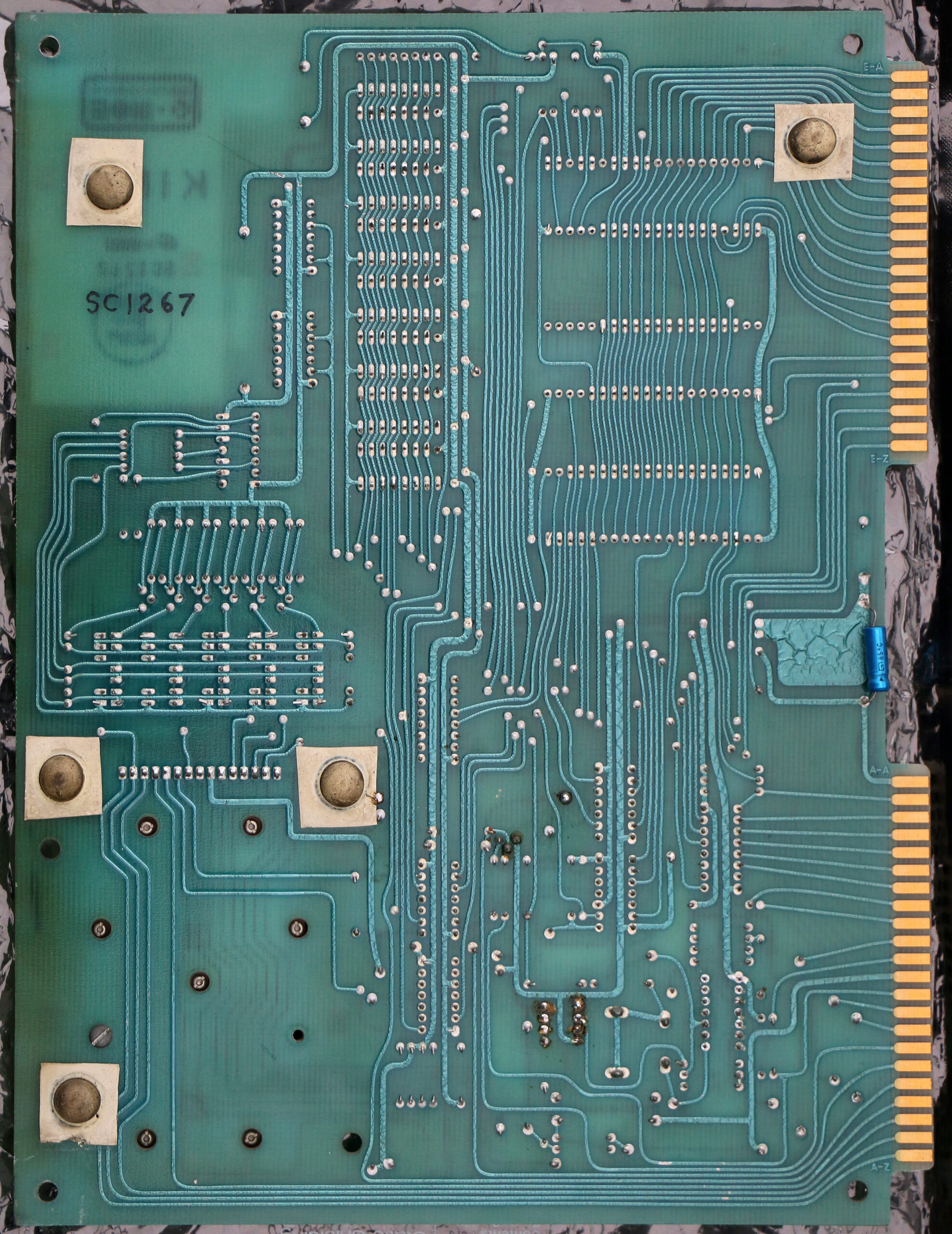

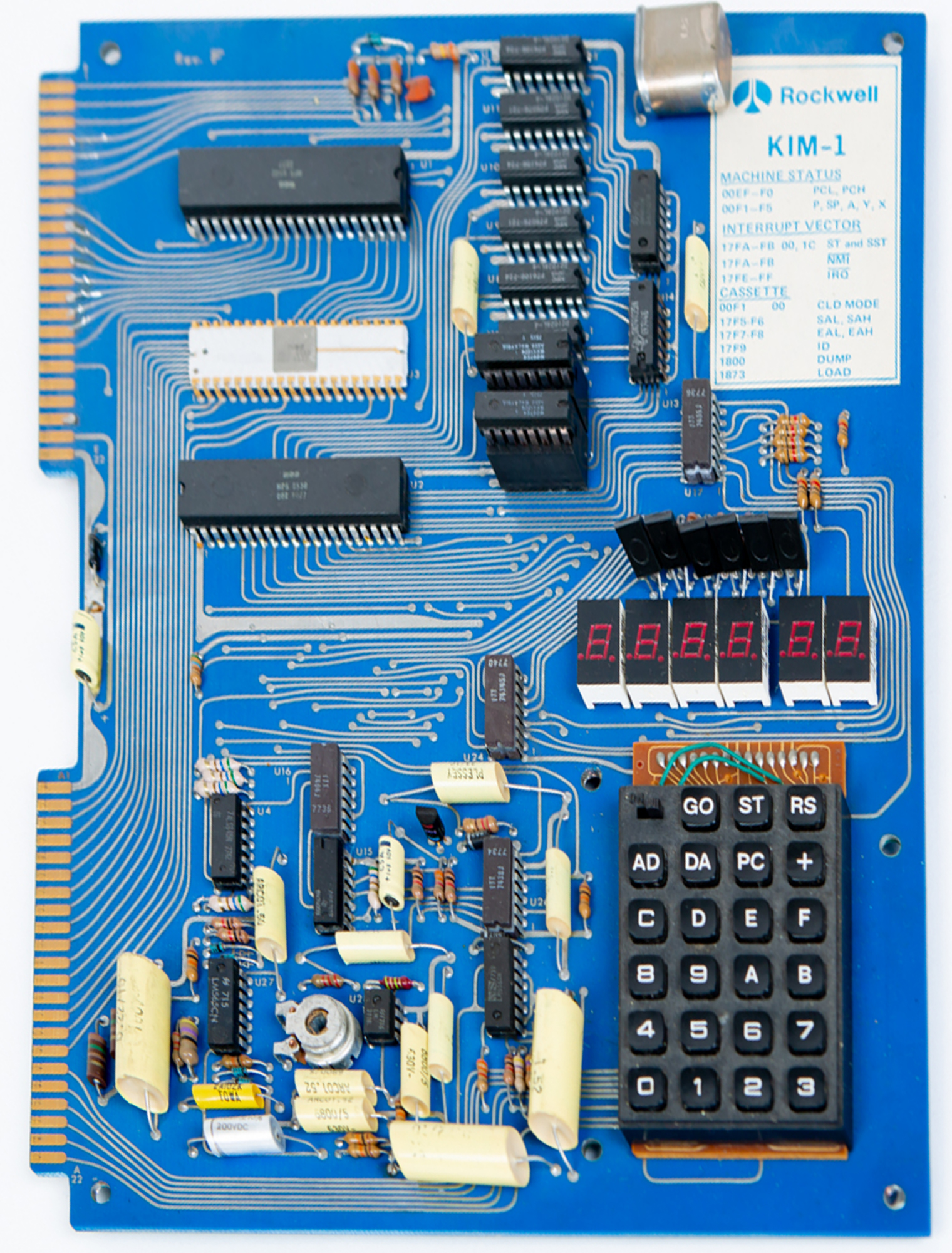

The KIM-1 was an OEM product by Rockwell, with its Rockwell branded documentation and a Rockwell sticker at the right top part covering the Commodore MOS label. I know of at least two versions by Rockwell, a Rev D and my Rev F.

Some companies made KIM-1 clones with the same specifications but with more modern SRAM (2114), see the KIM-1 related page.

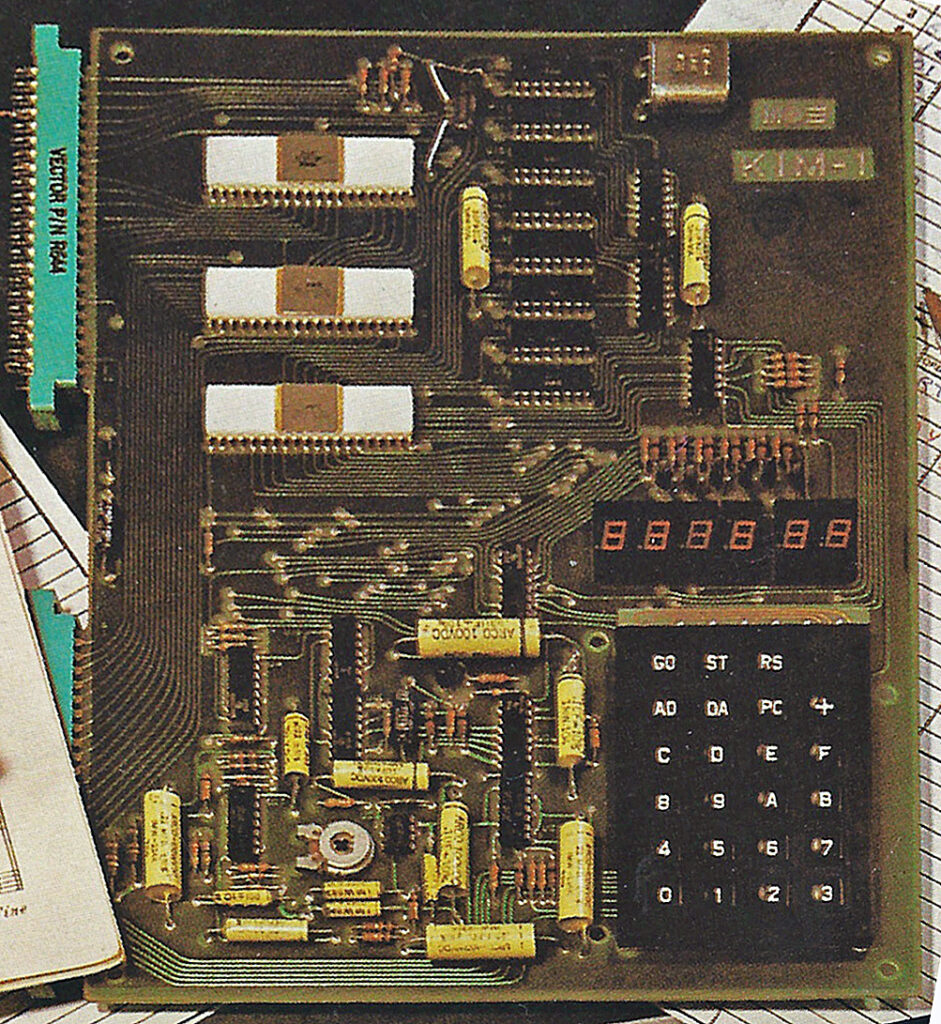

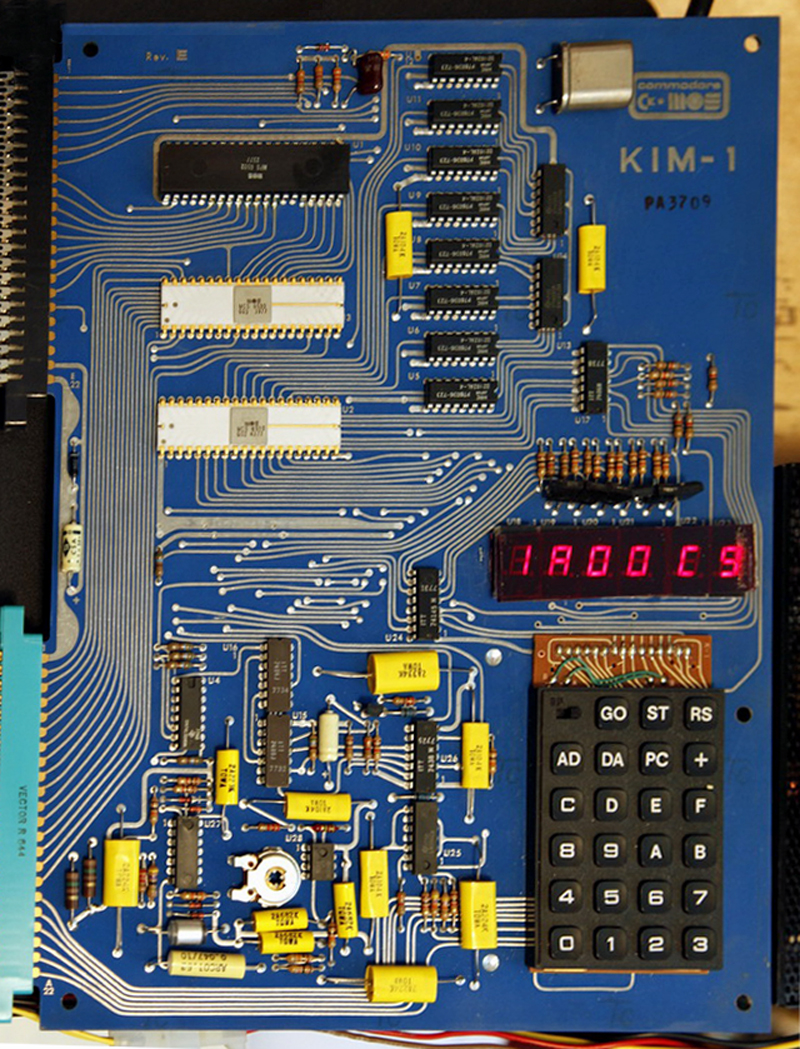

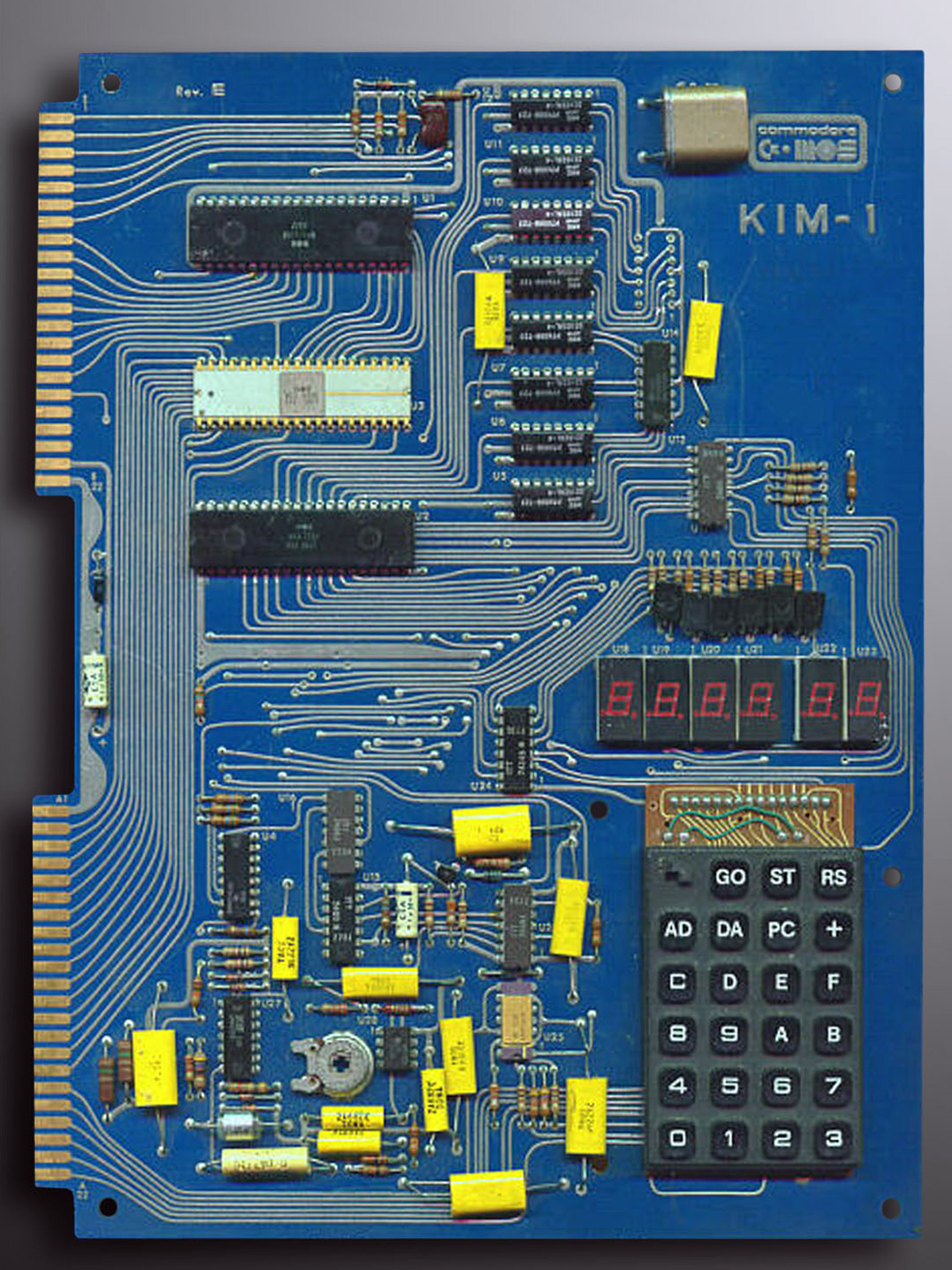

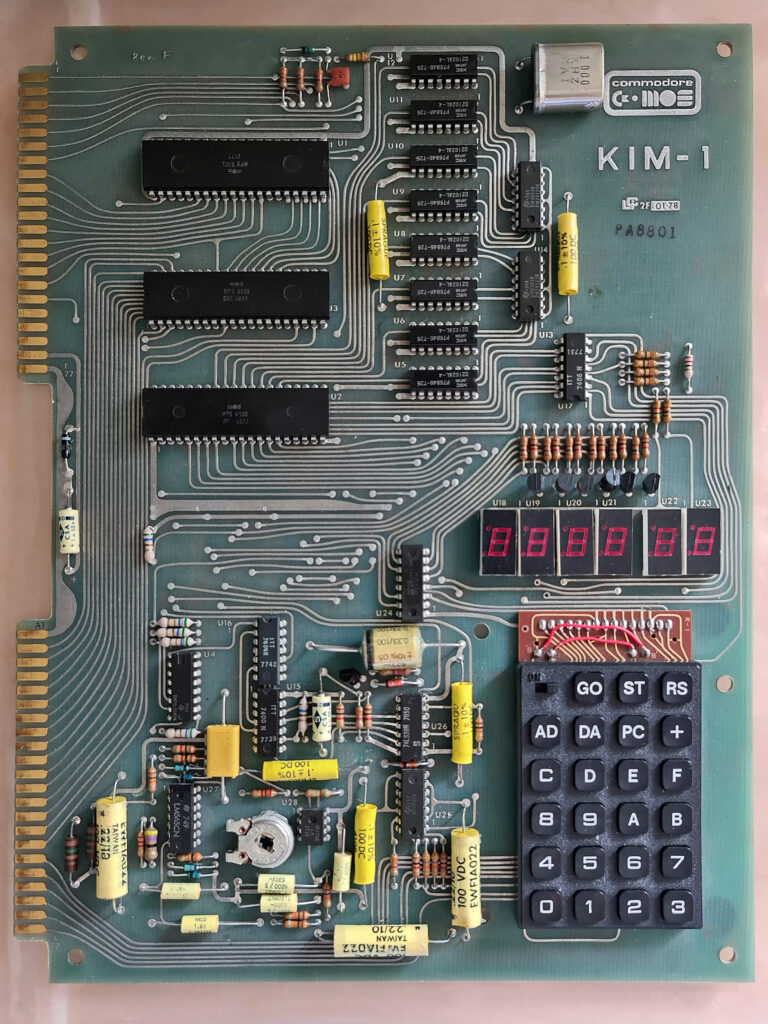

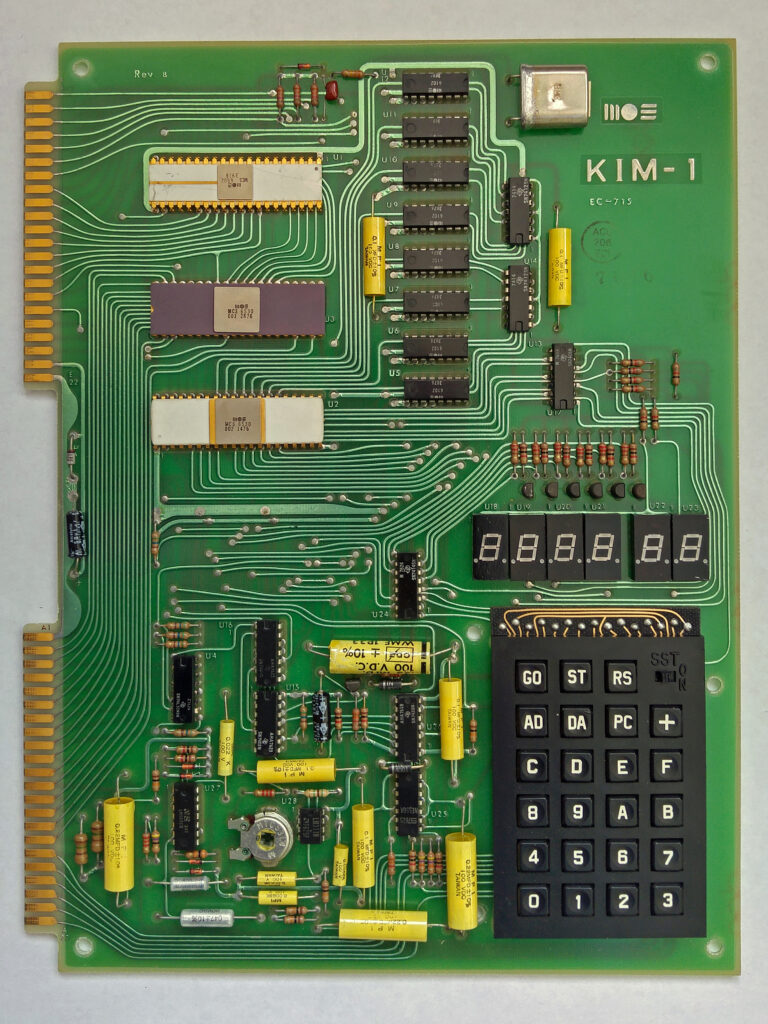

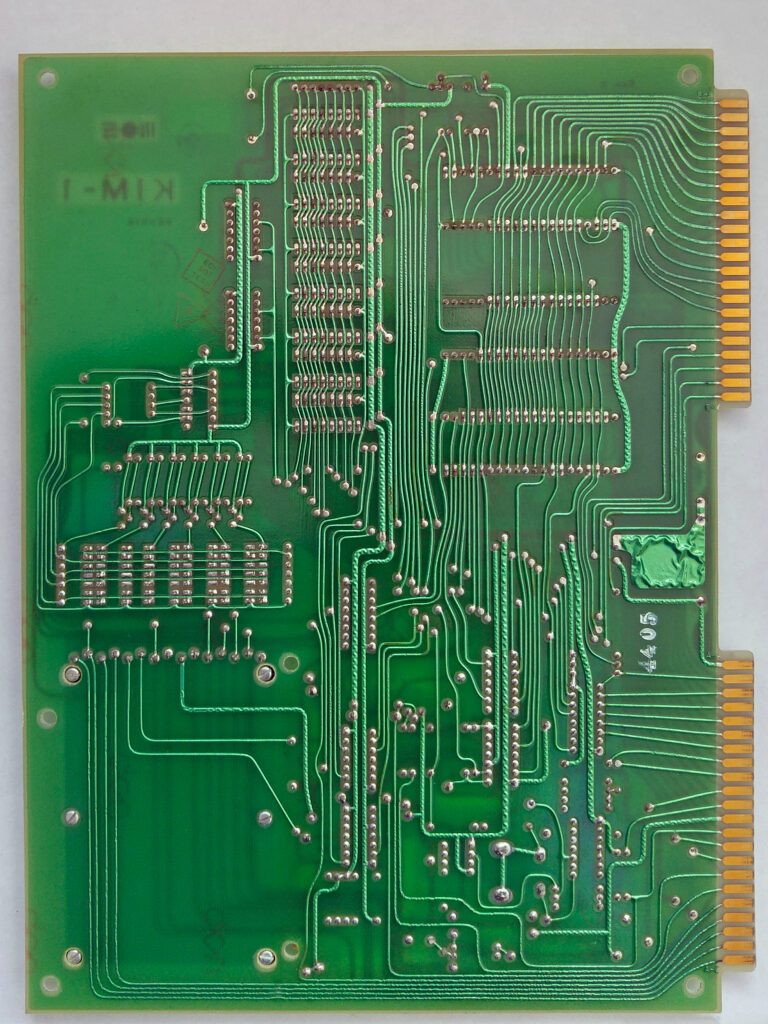

The visible changes were cosmetic: color of PCB, labeled MOS first and Commodore later, and housing of ICs used (white and violet ceramic to black on the later revisions.).

Early on in the Rev A period the 6502 with defective ROR instruction was replaced with the repaired 6502, this NMOS IC continued to be the CPU to the latest revision.

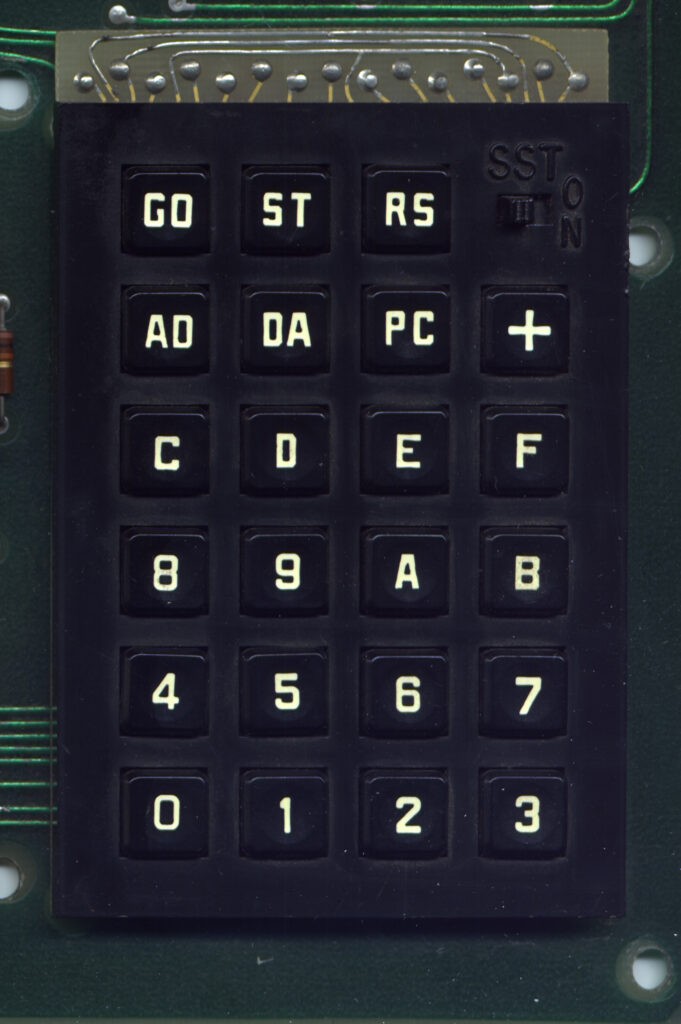

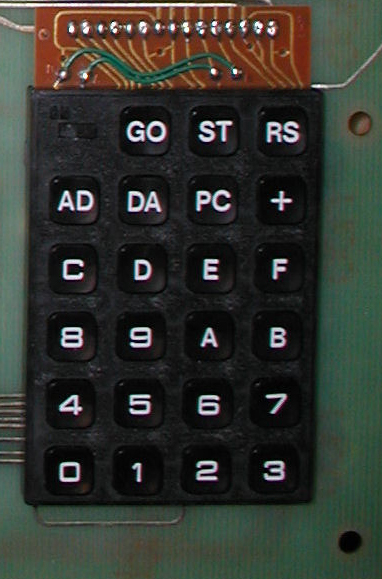

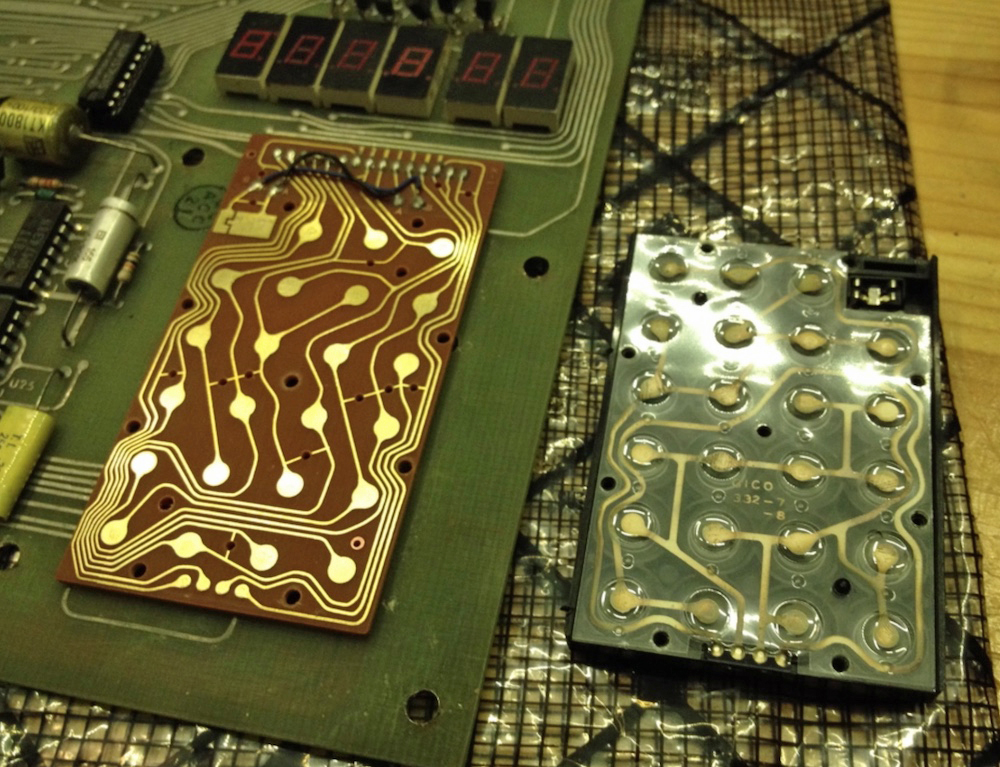

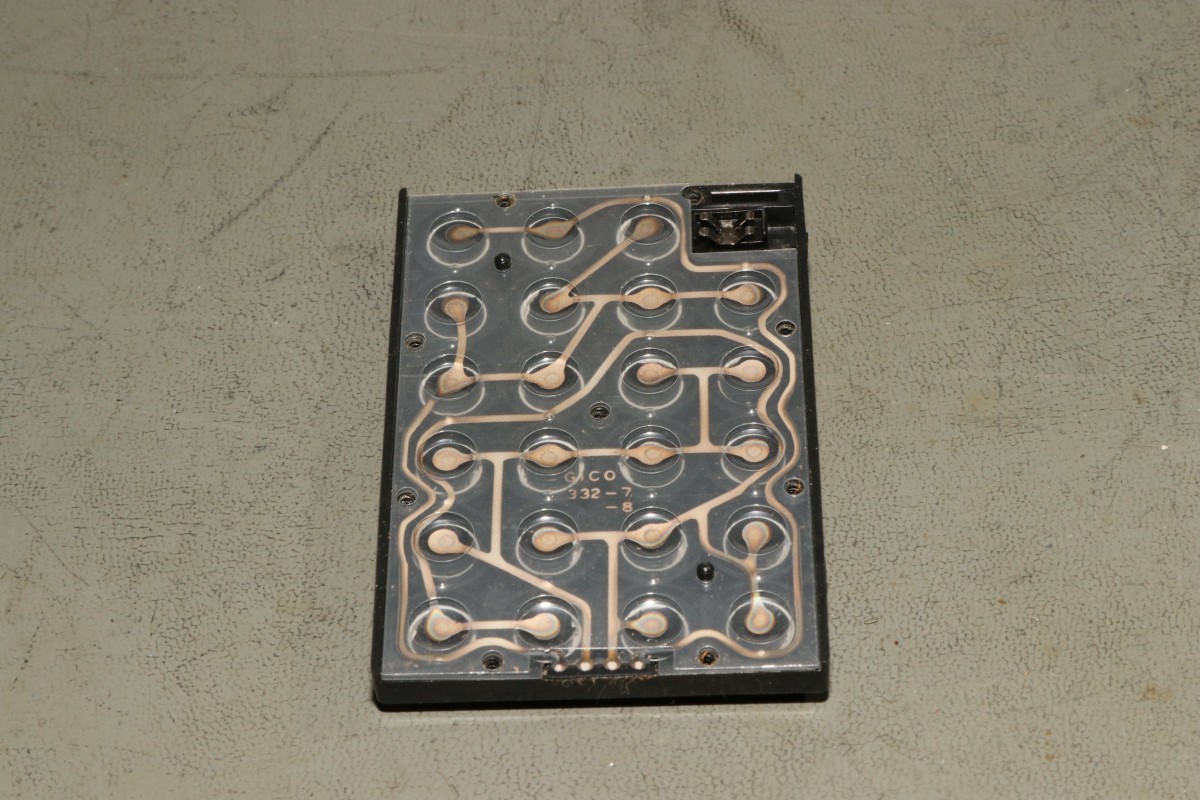

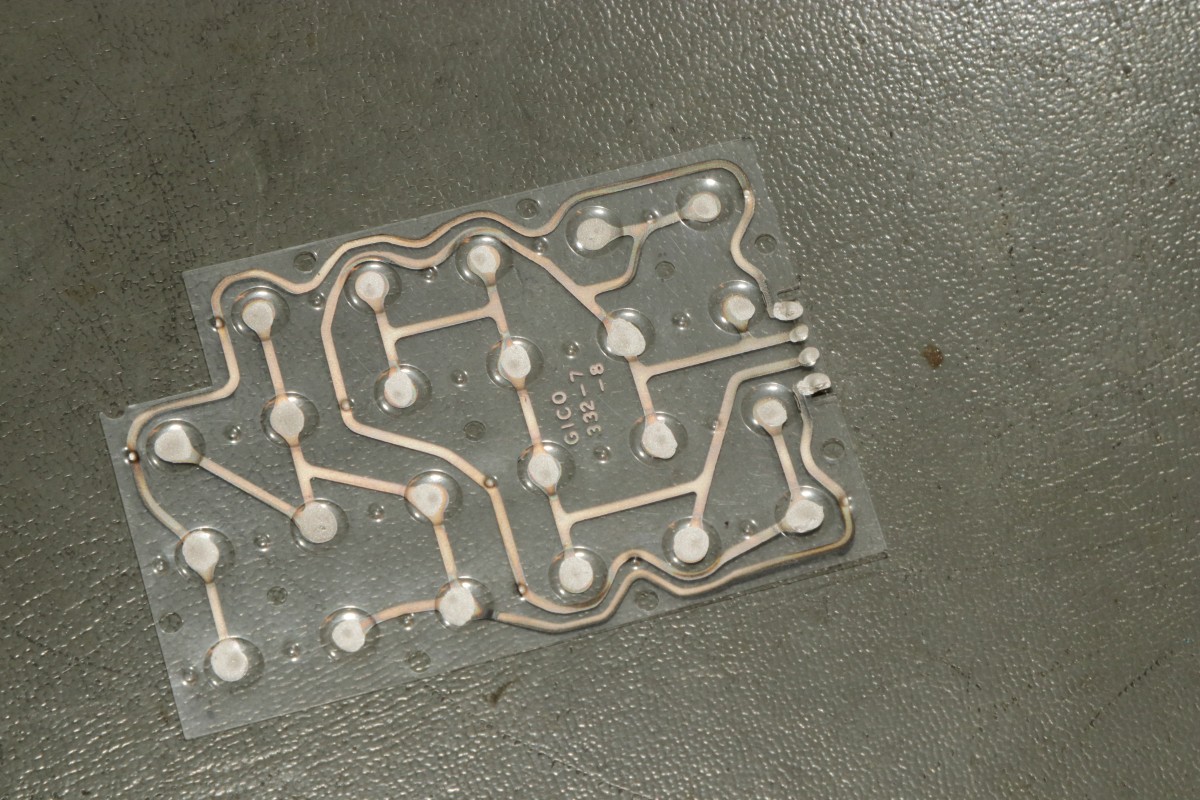

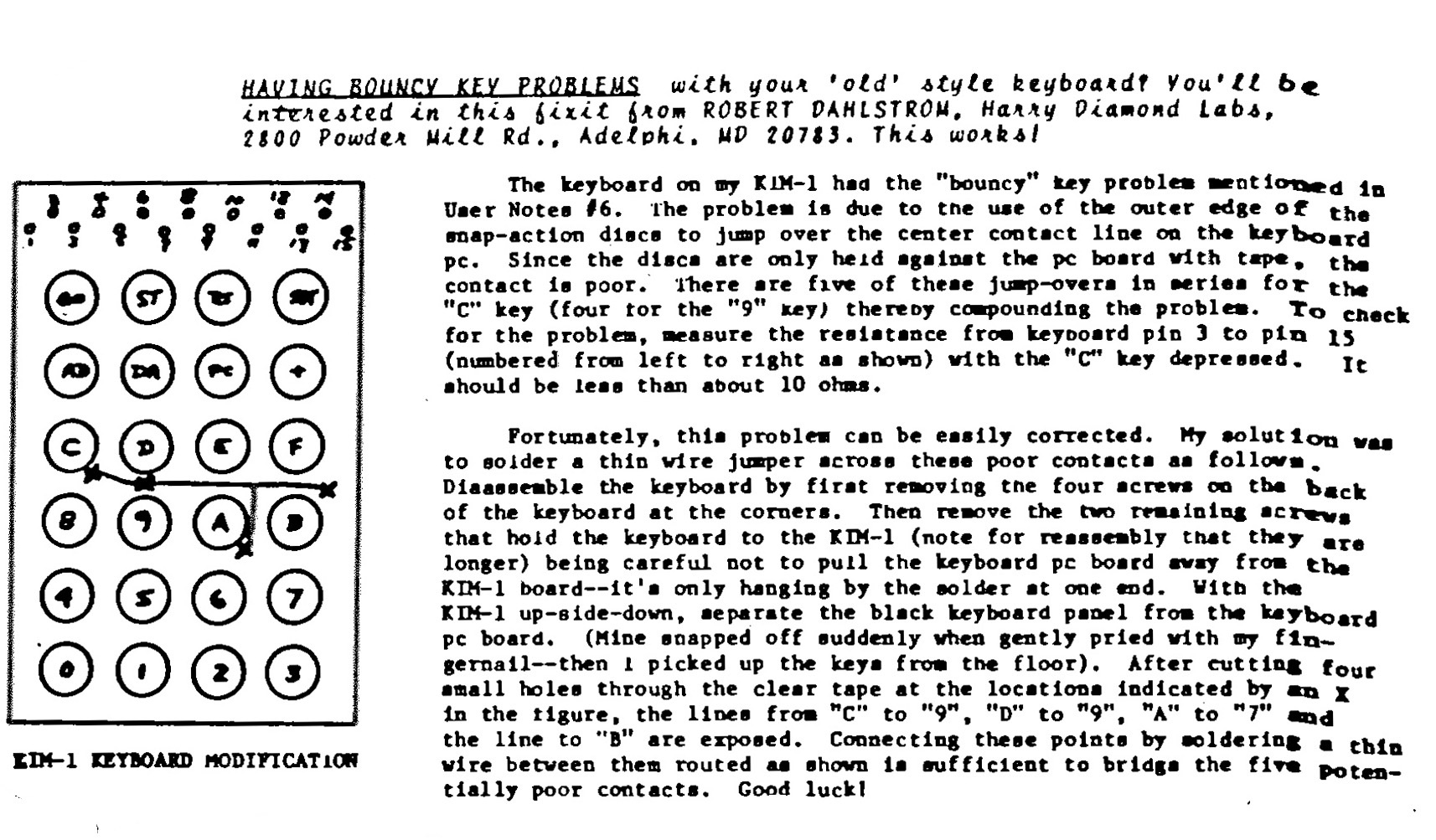

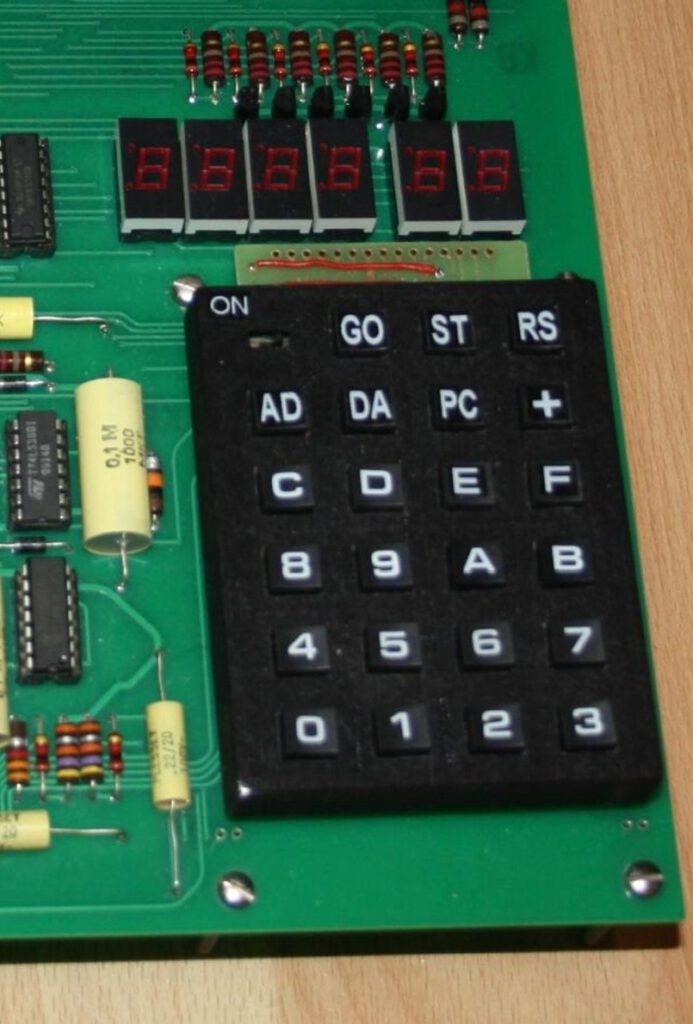

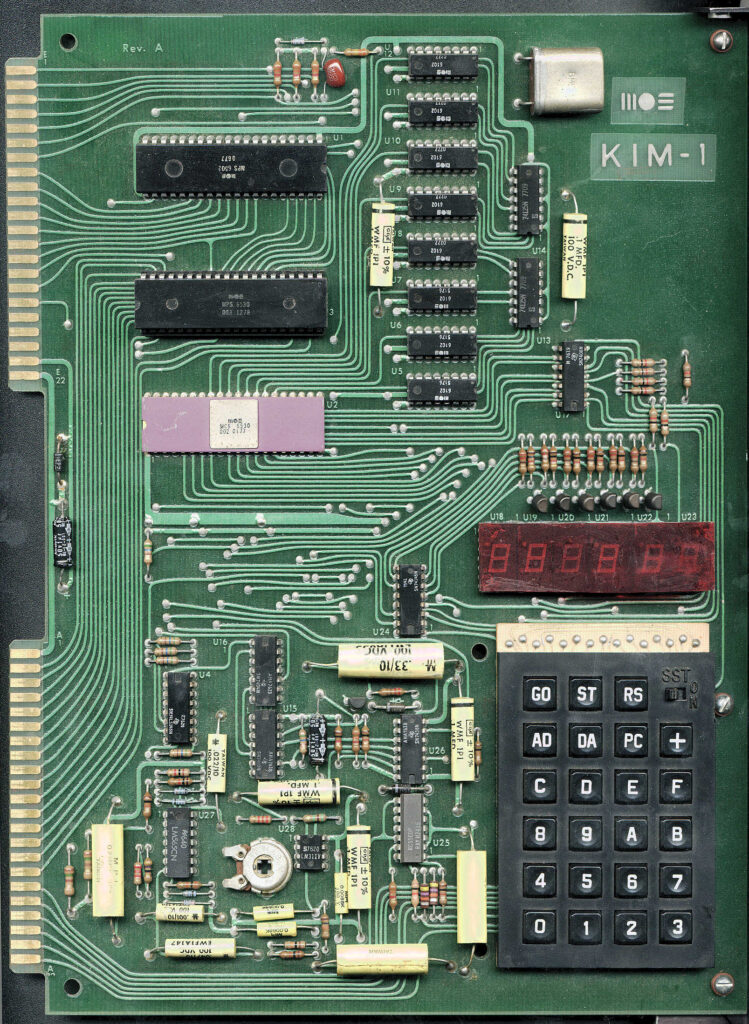

A real change was the keyboard. A different one was used by Commodore, with the SST switch moved to the other side of the top row. See the page about the differences and how to repair.

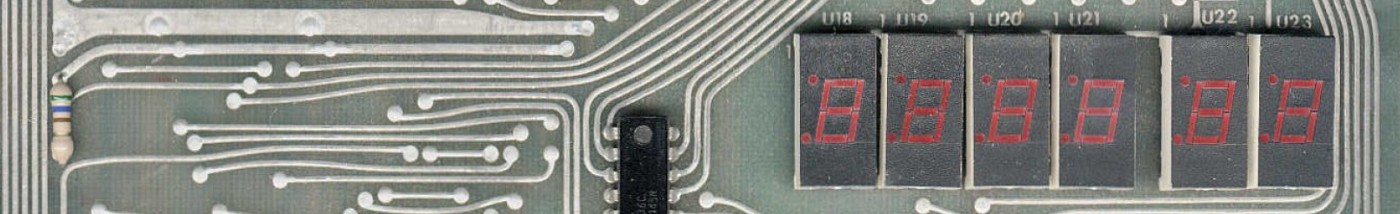

Components used were of course the NMOS 6502 CPU and the RRIOTs 6530-002 and -003. I see many manufacturing dates, from 1975 to 1980 on the IC’s. It seems RRIOTs were not made after that date and enough stock was available to build the Rev F. The SRAMs were in the beginning MOS 6102s, later the equivalent (and more reliable) 2102 took its place. LED displays, TTL and transistors came from the then current manufacturers and varied a lot. The capacitors were mainly the distinct yellow axial type.

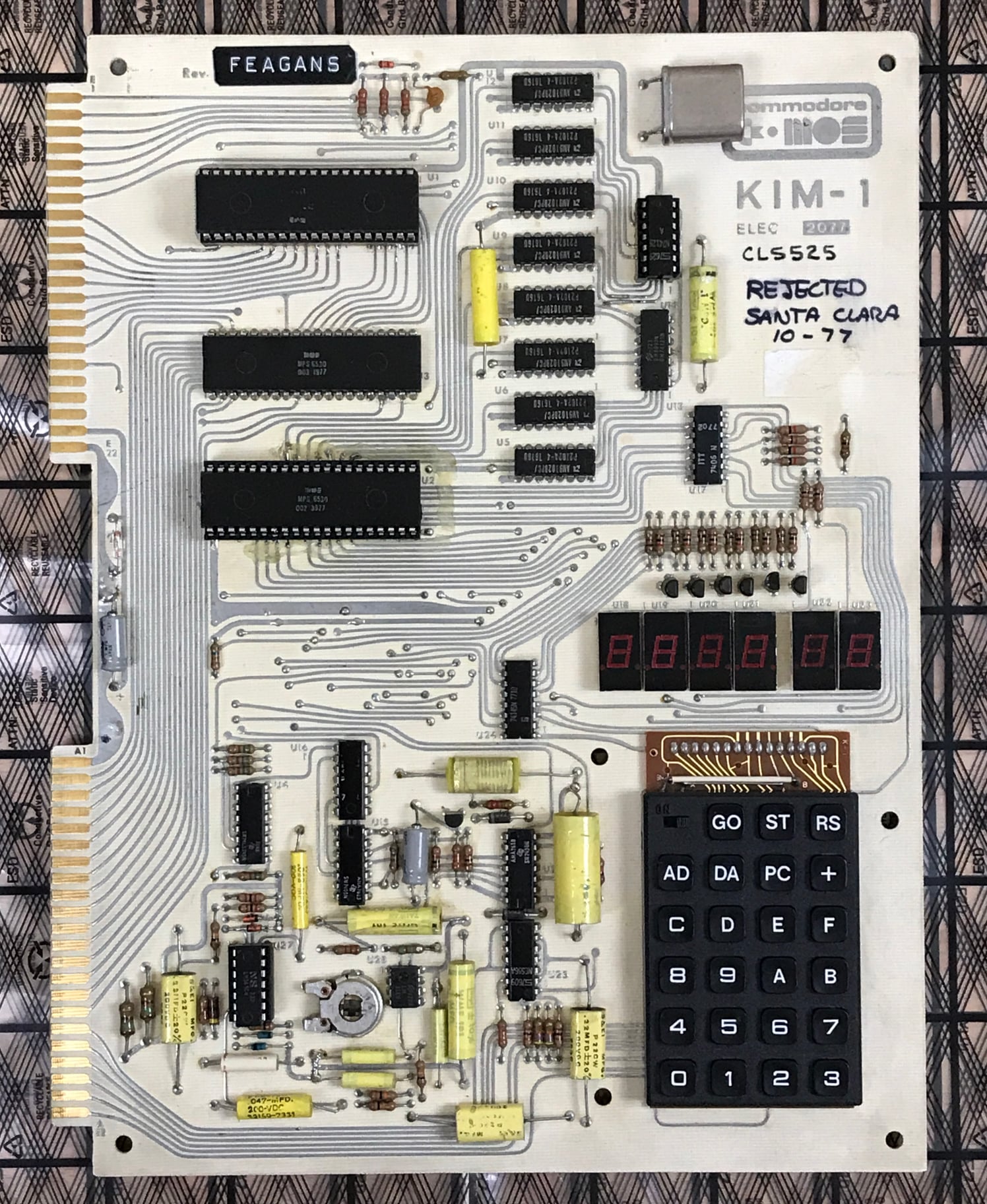

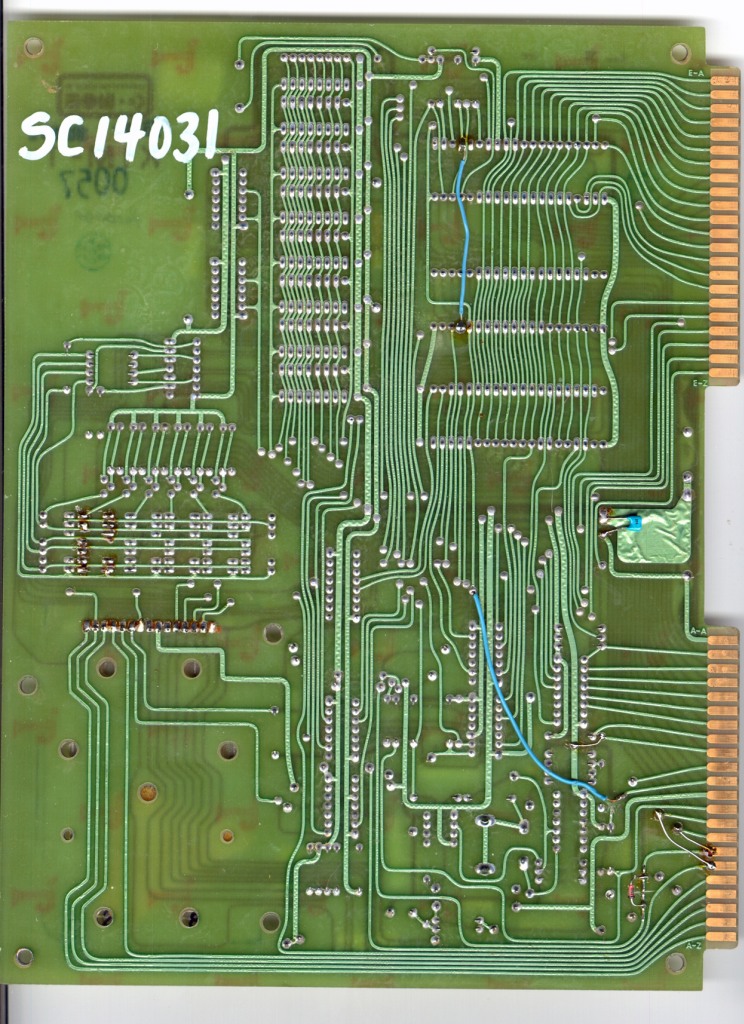

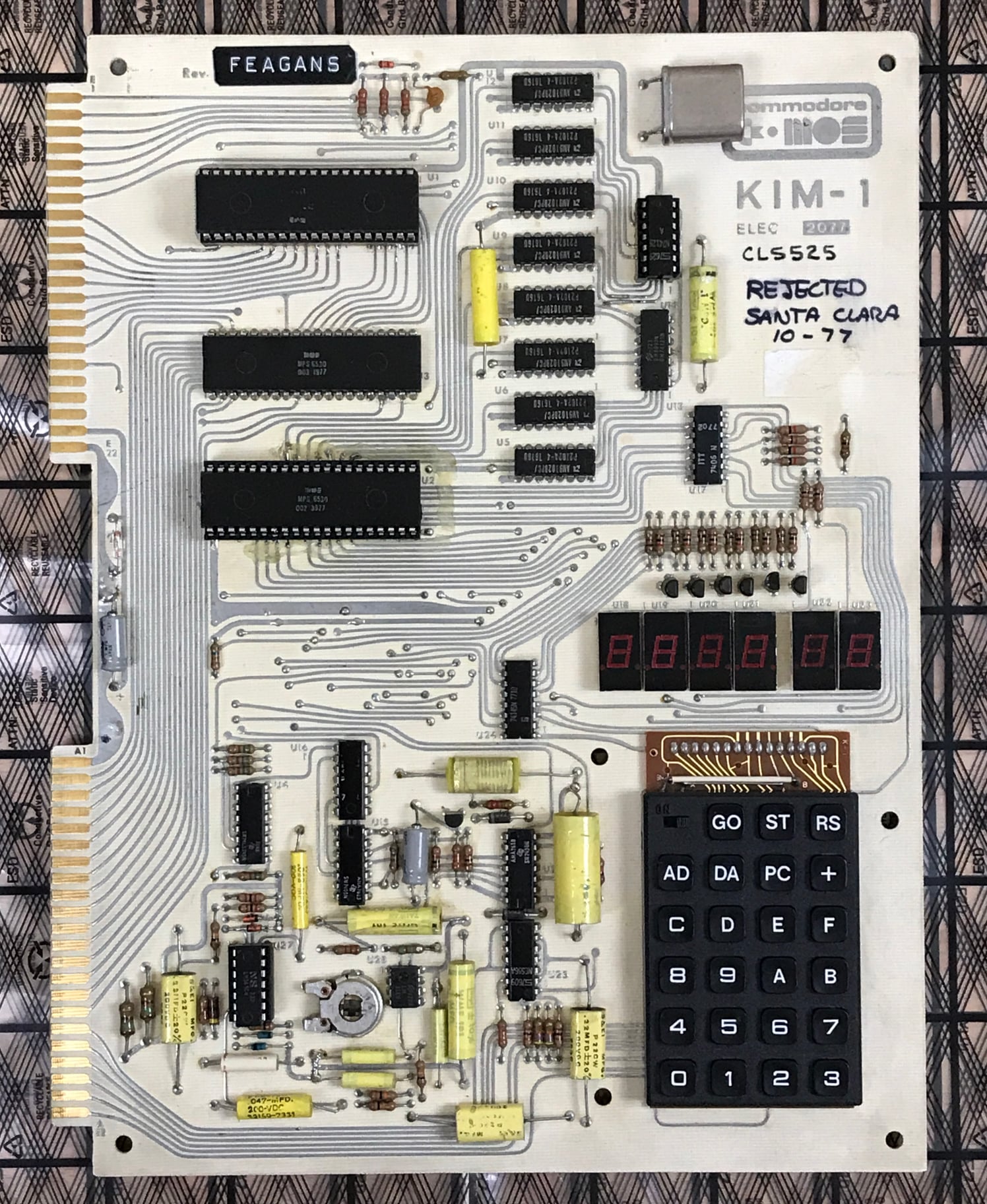

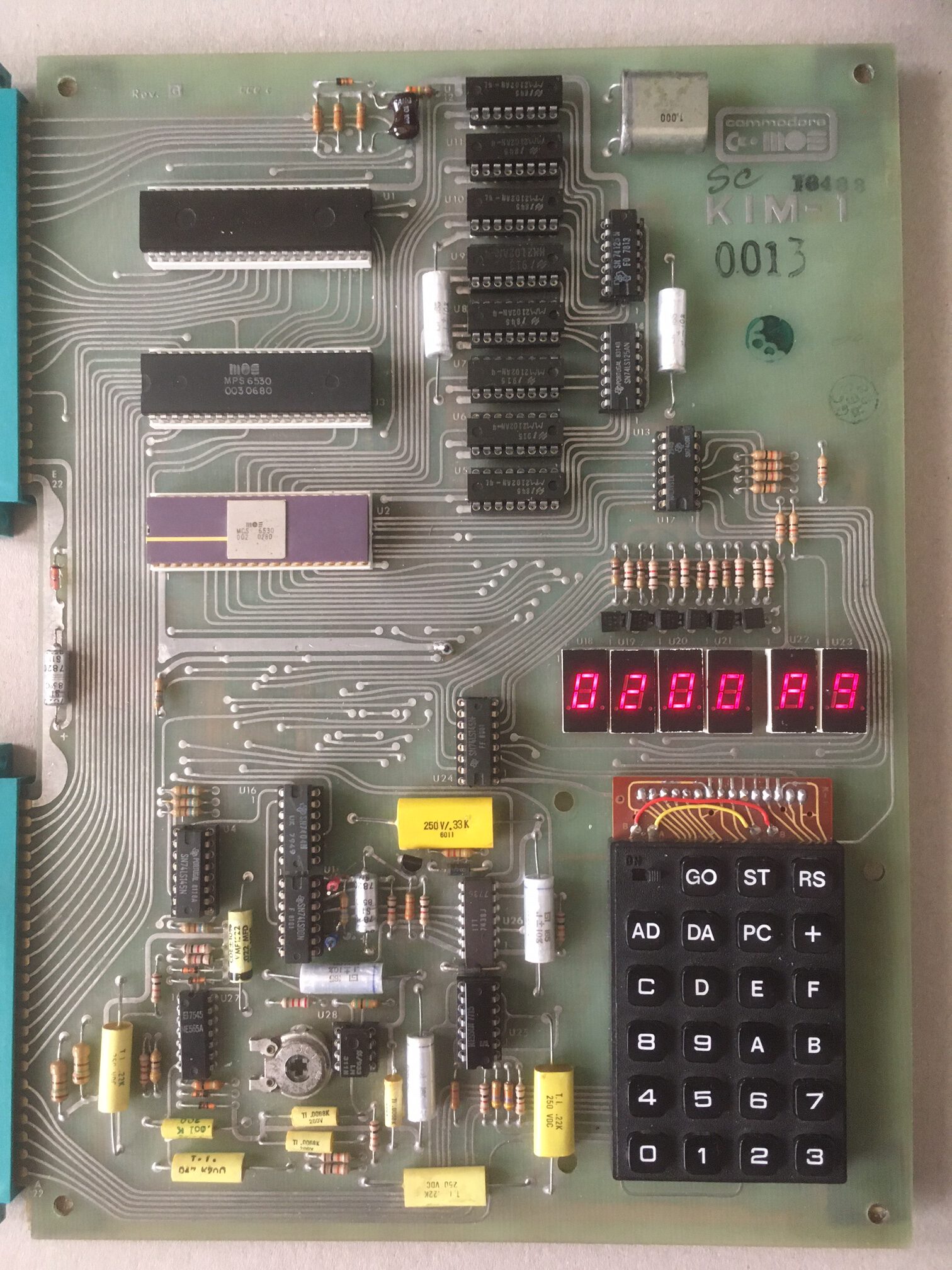

Serial numbers (thanks Dave McMurtrie for this information) appear on many KIM-1s. Not all, perhaps the handwriting wears off. Early ones (to ReV B) go without a prefix (most) or a ‘M’. On later Rev’s, the Commodore ones, numbers have a prefix PA or SC. SC stands for Santa Clara, PA for Norristown, Pennsylvania, production locations of Commodore at that time. Perhaps the number on that Rev G SC38488 means there are at least that many KIM-1s produced in Santa Clara? A Rev F with PA9047? If that is really a sequence number, how many KIM-1’s were produced? 50000? or more?

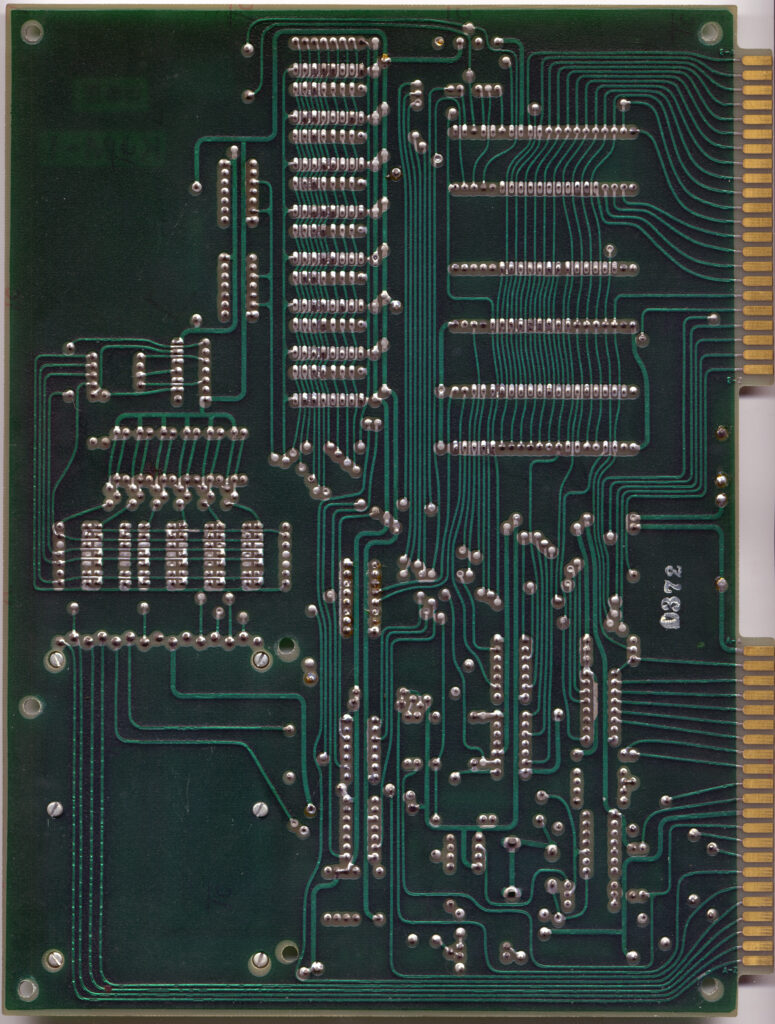

Here after are shown images of the revisions, some from photos by myself, others from the internet. I have tried to name the origin, if I failed and you are the origin, please report it.

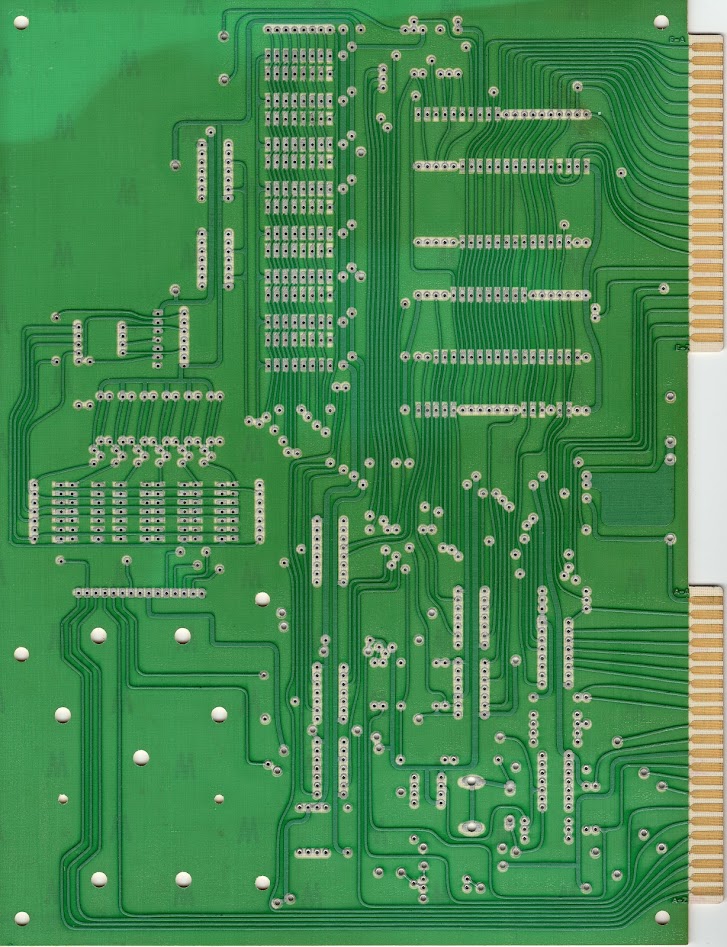

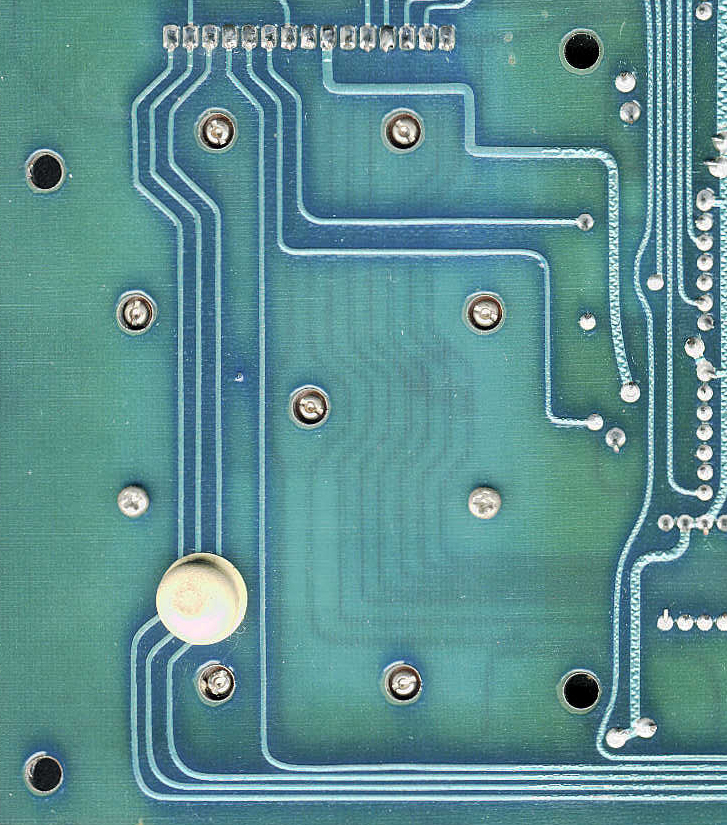

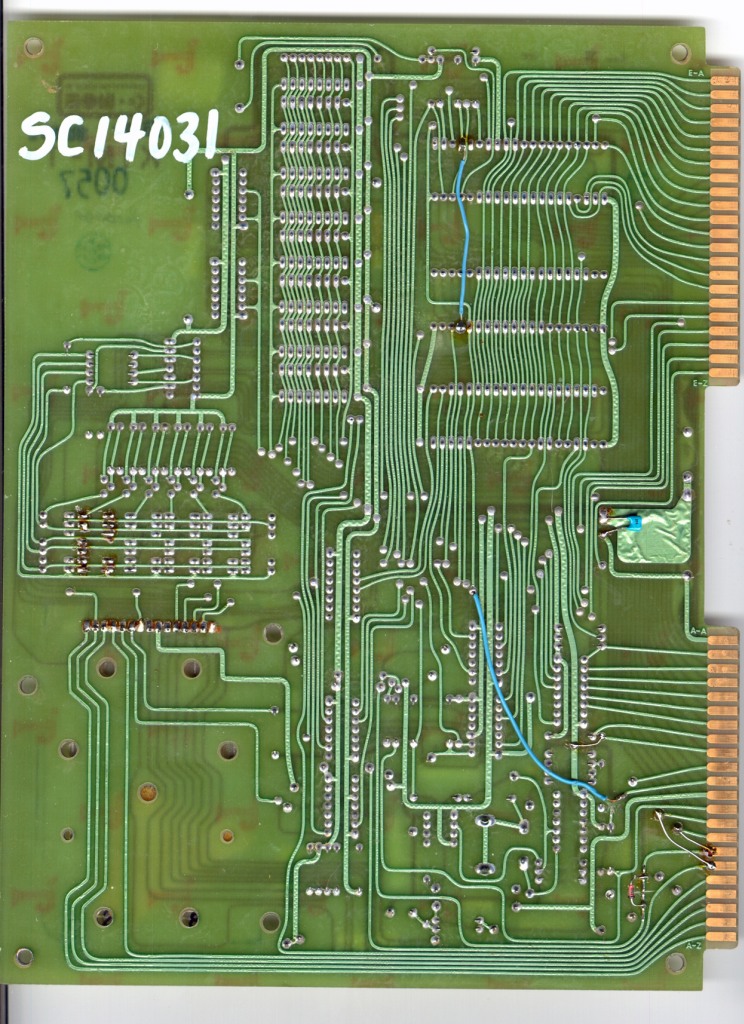

If available, both front and back are shown.

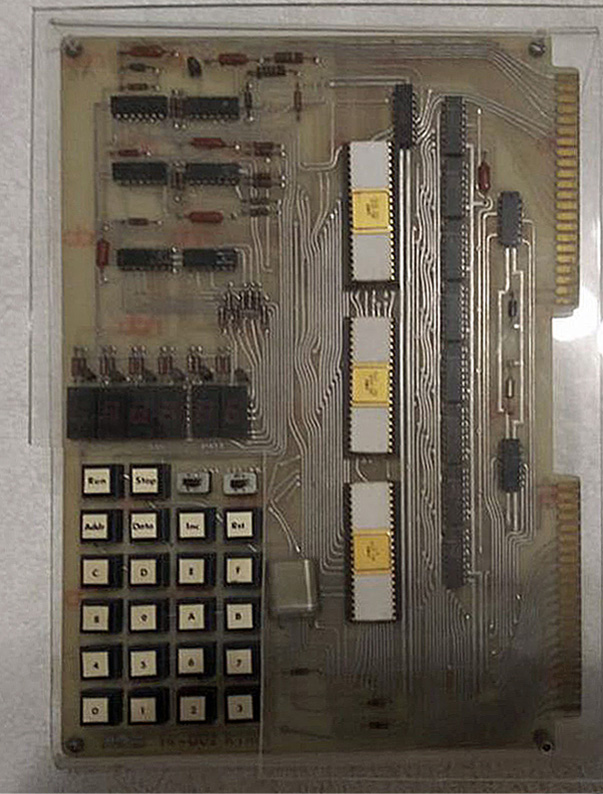

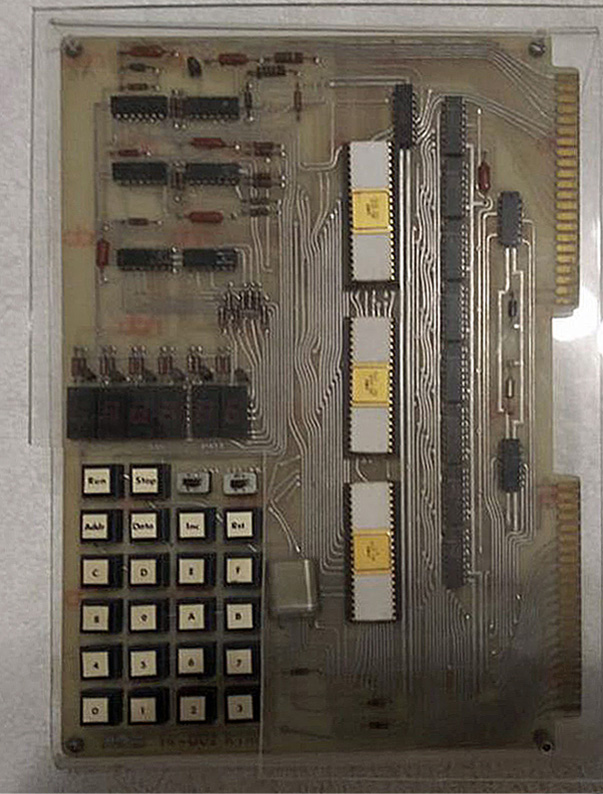

Prototype KIM-1

On team6502 About page I found a photo of a prototype KIM-1 at MOS Technologies, Terry Holdt has this in his office.

The layout is different from the final product, everything seems to be present on this prototype except the audio cassette components.

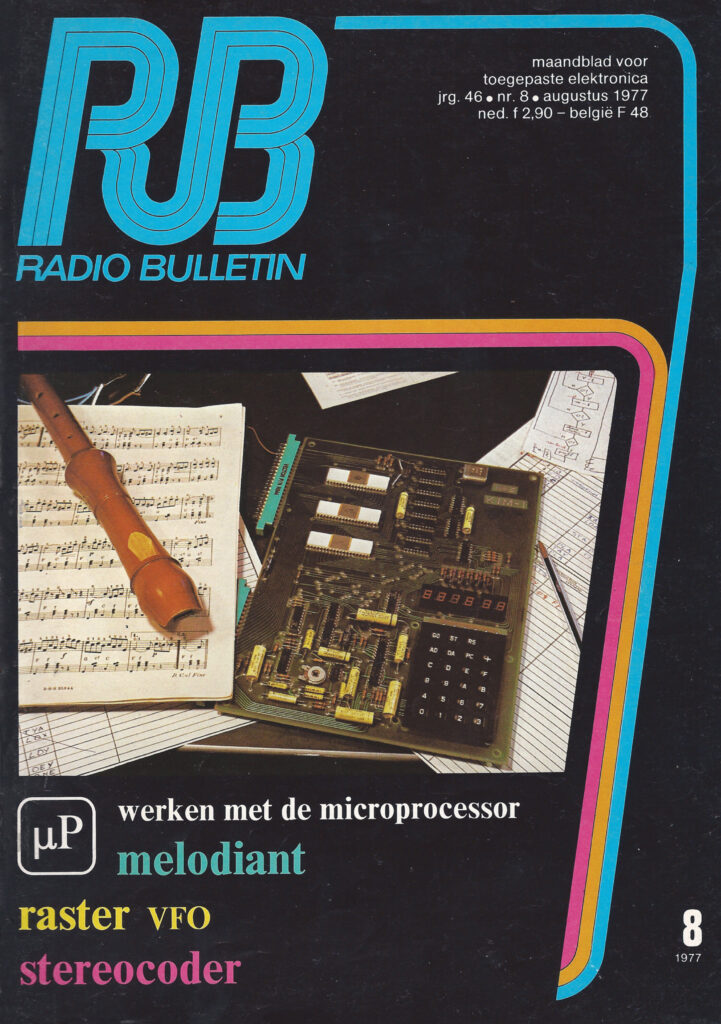

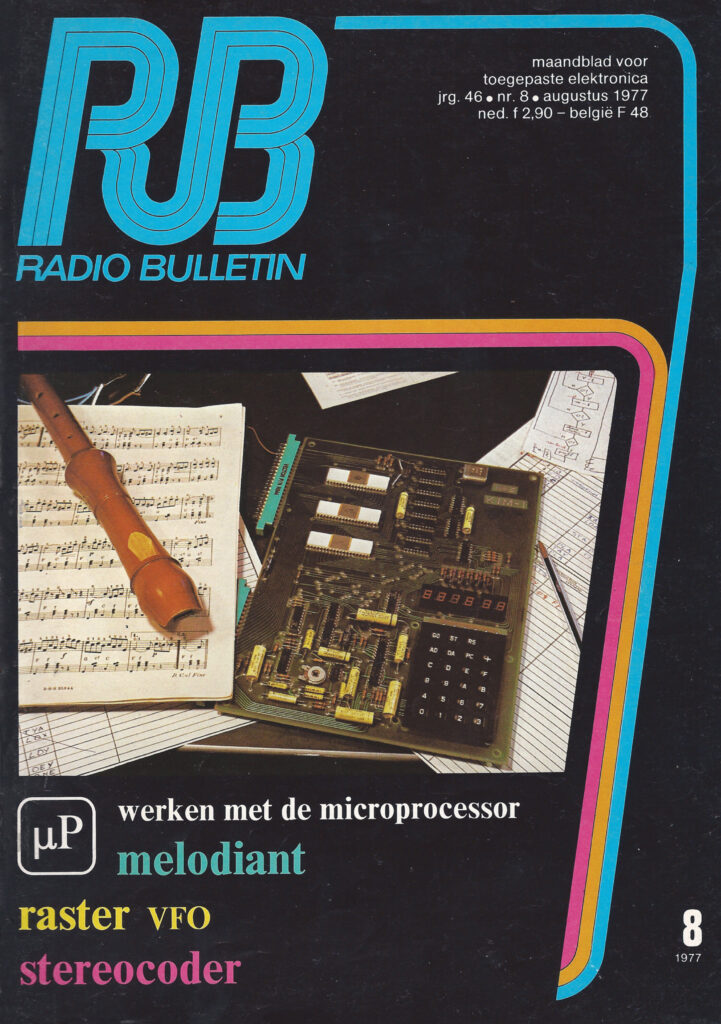

First KIM-1 at Radio Bulletin

In 1977 Dick Boer started publishing about the KIM-1 and we acquired a first edition KIM-1, shown on the front page of Radio Bulletin August 1977.

This was the first KIM-1 I saw and touched!

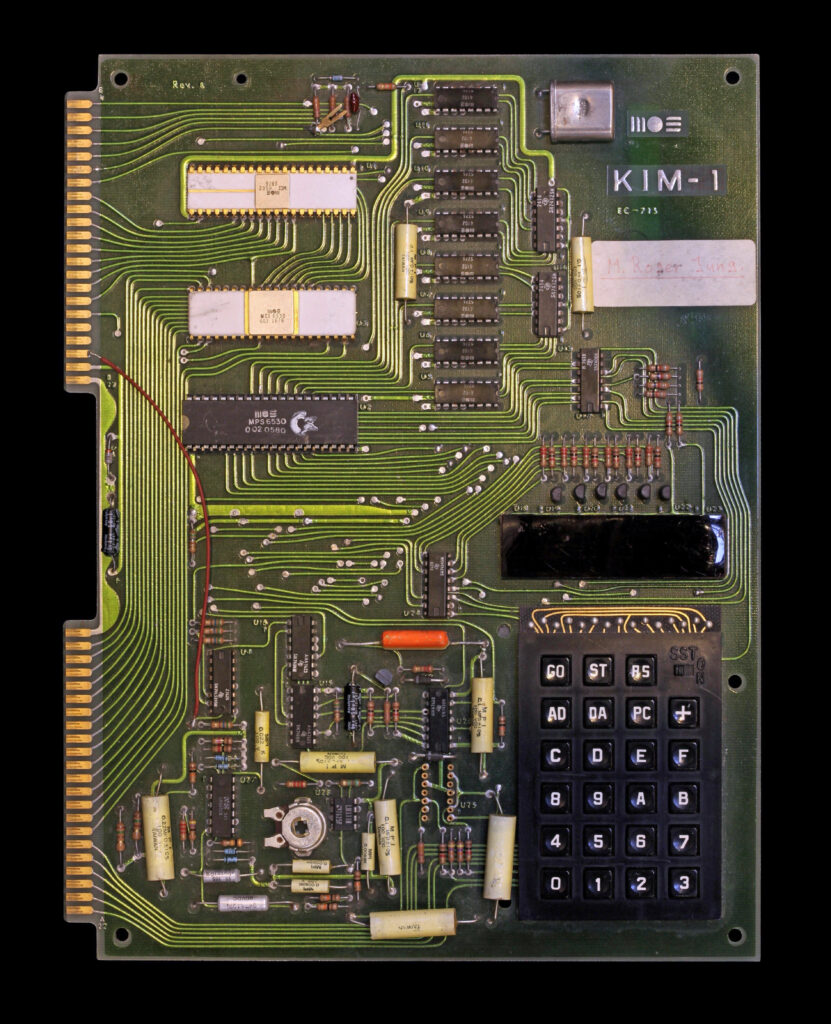

No revision, 1976

My KIM-1 first version, CPU needs to be replaced with original

From pagetable.com

From pagetable.com

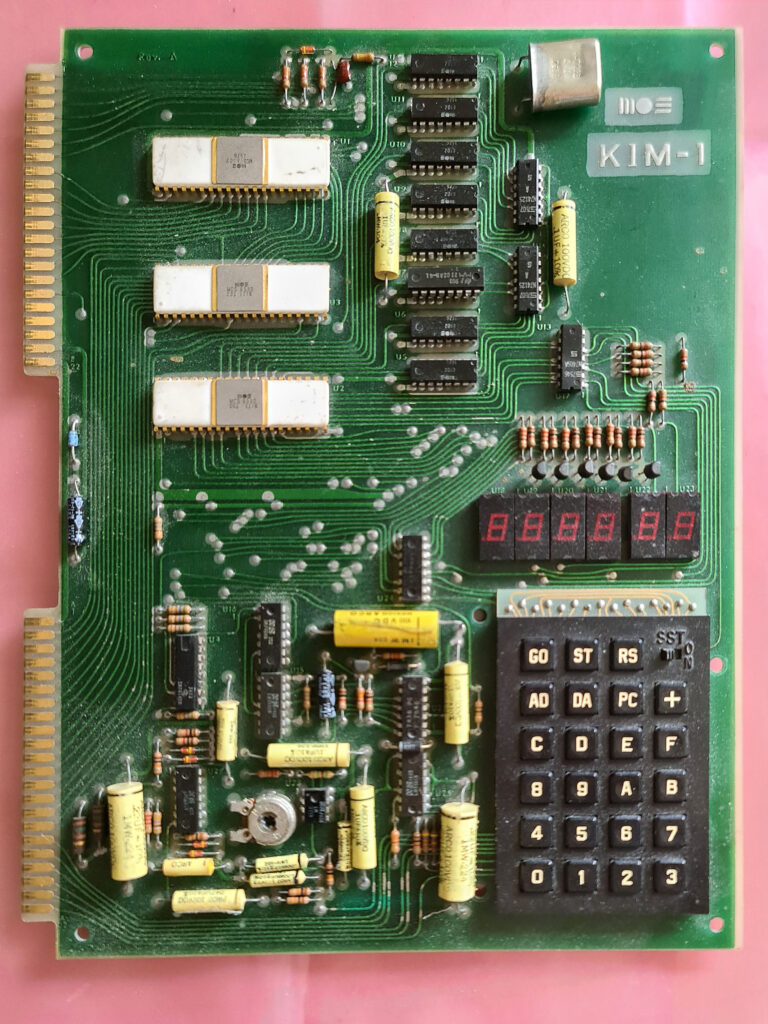

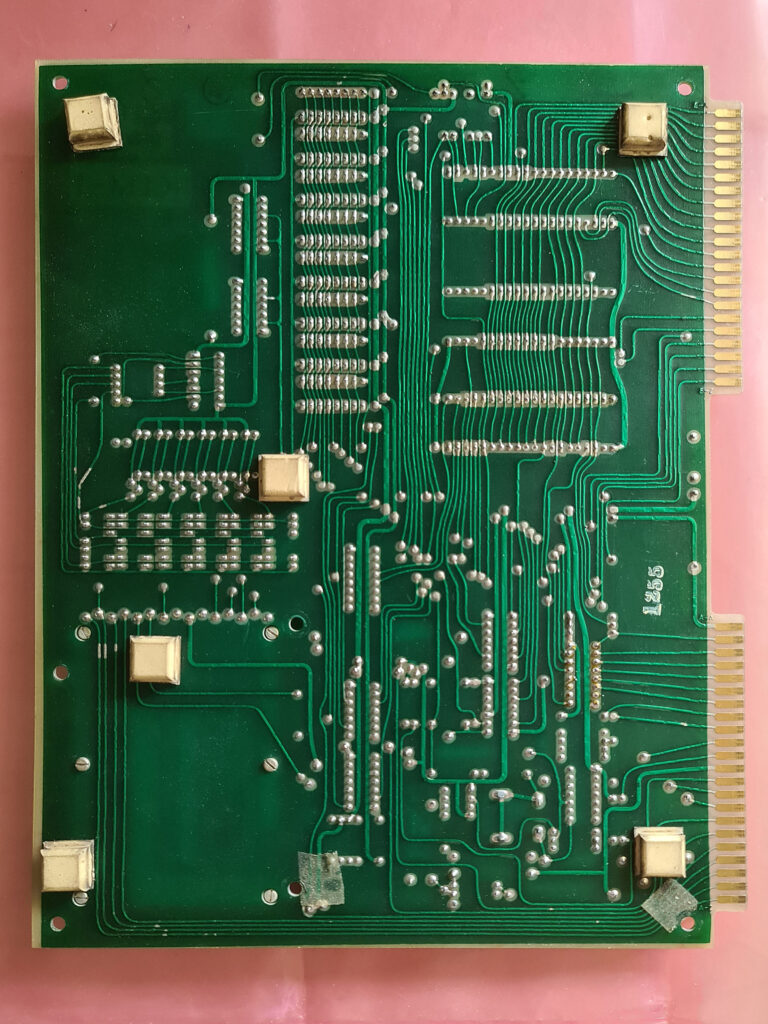

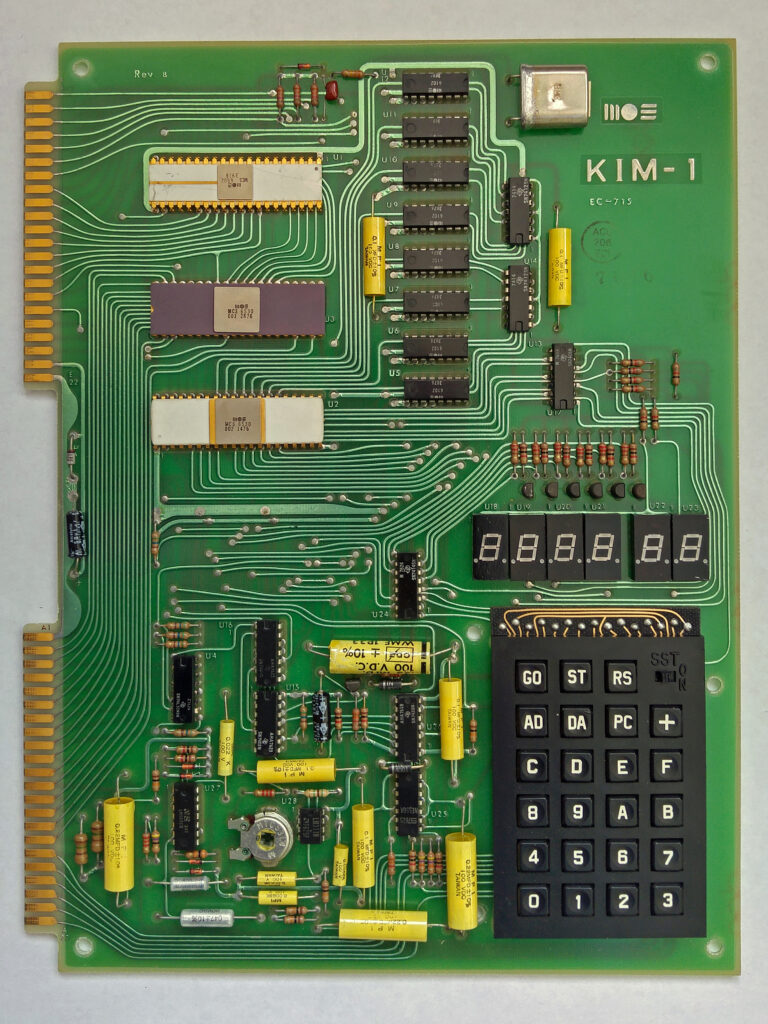

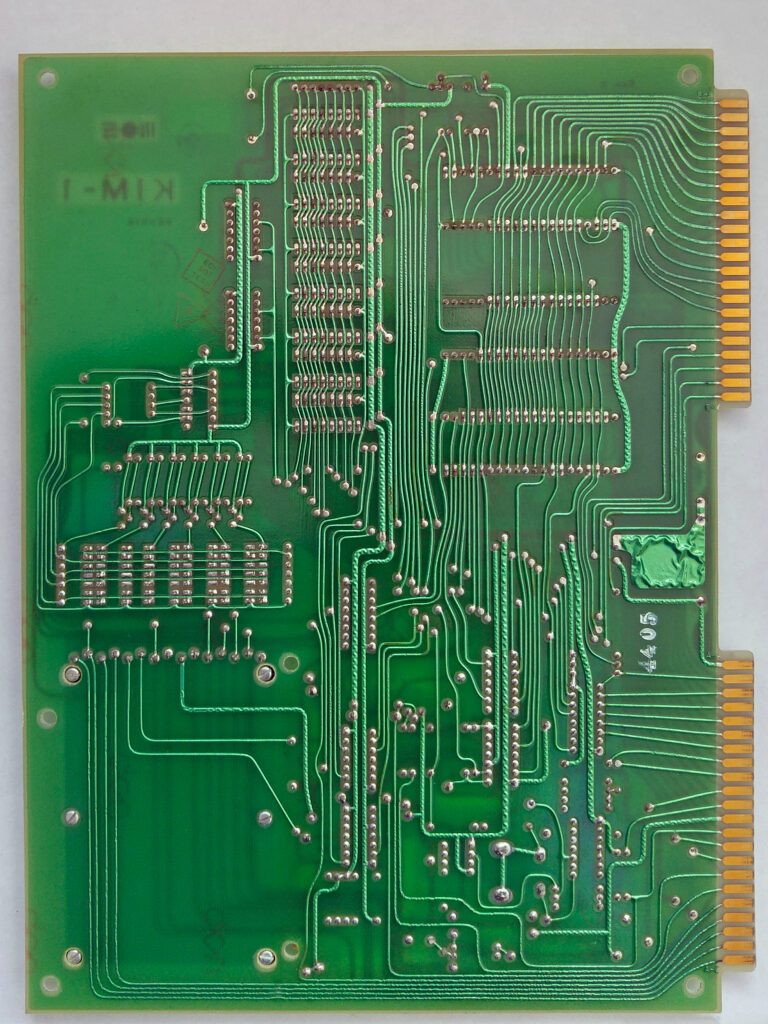

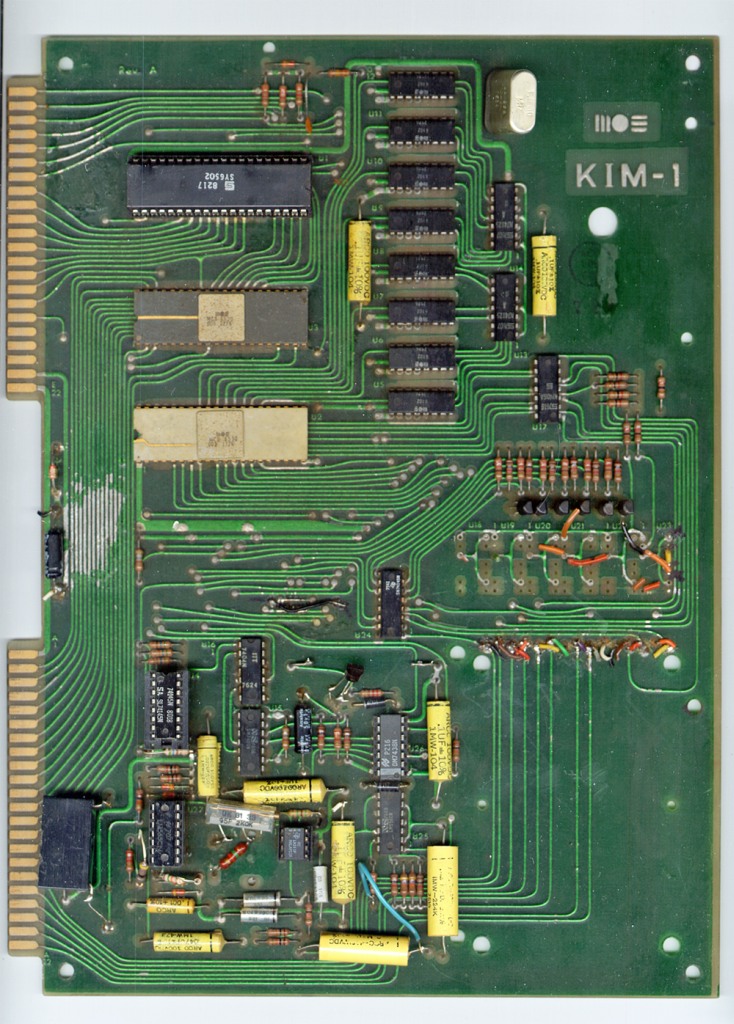

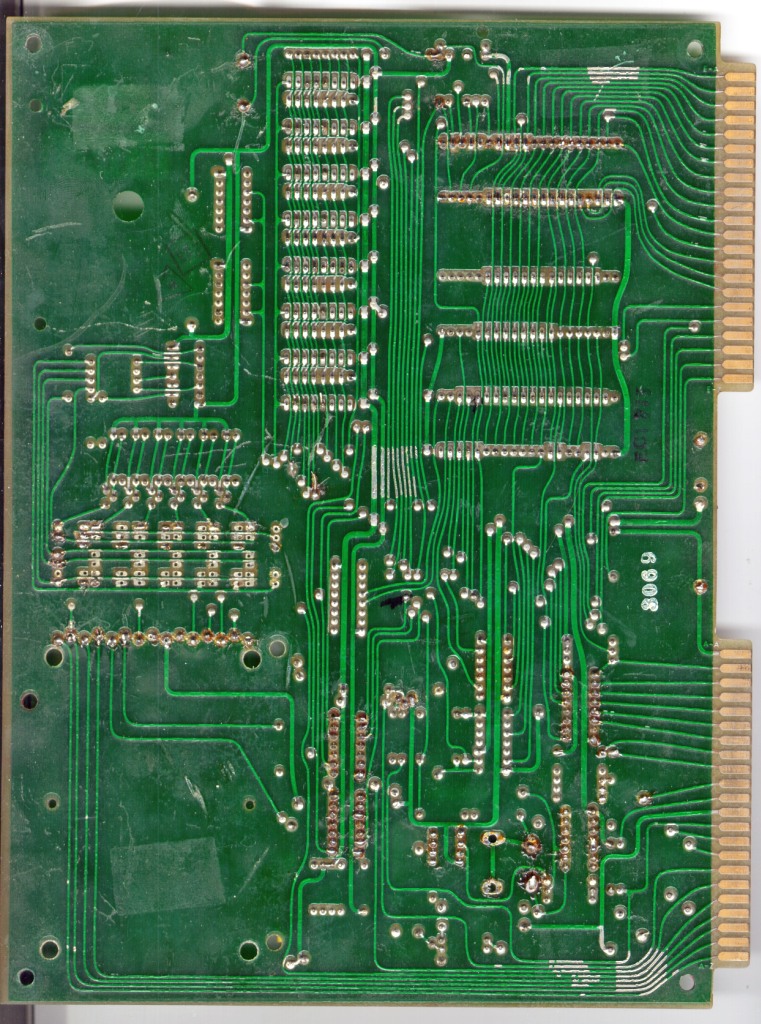

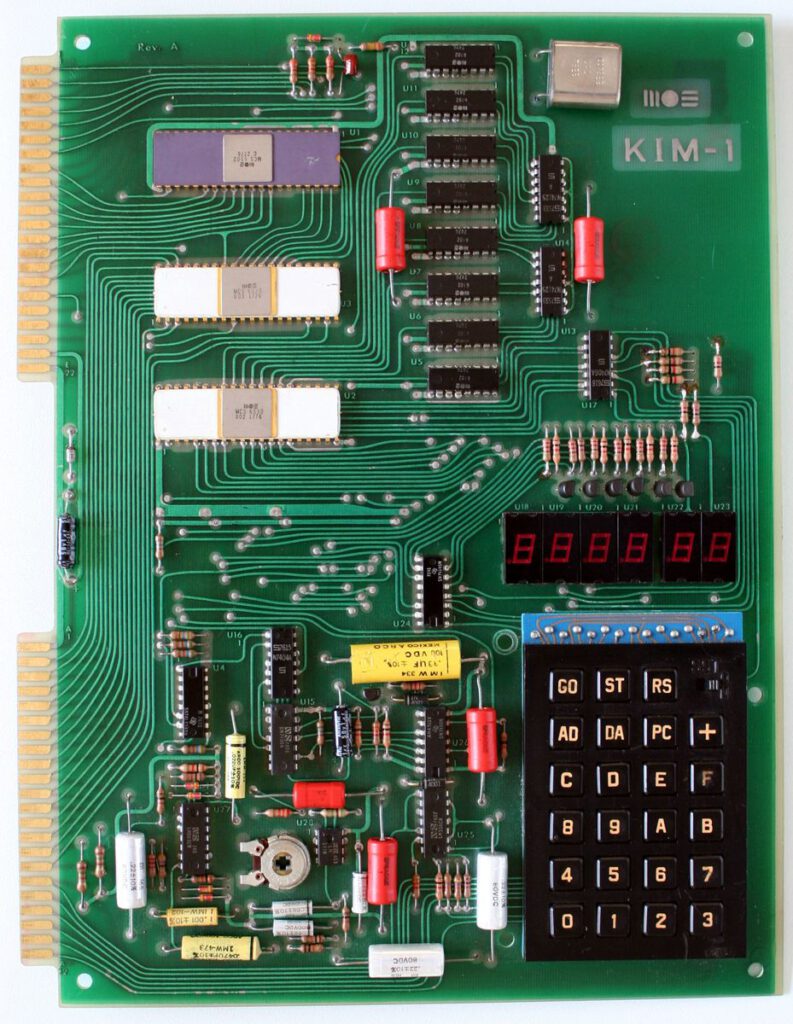

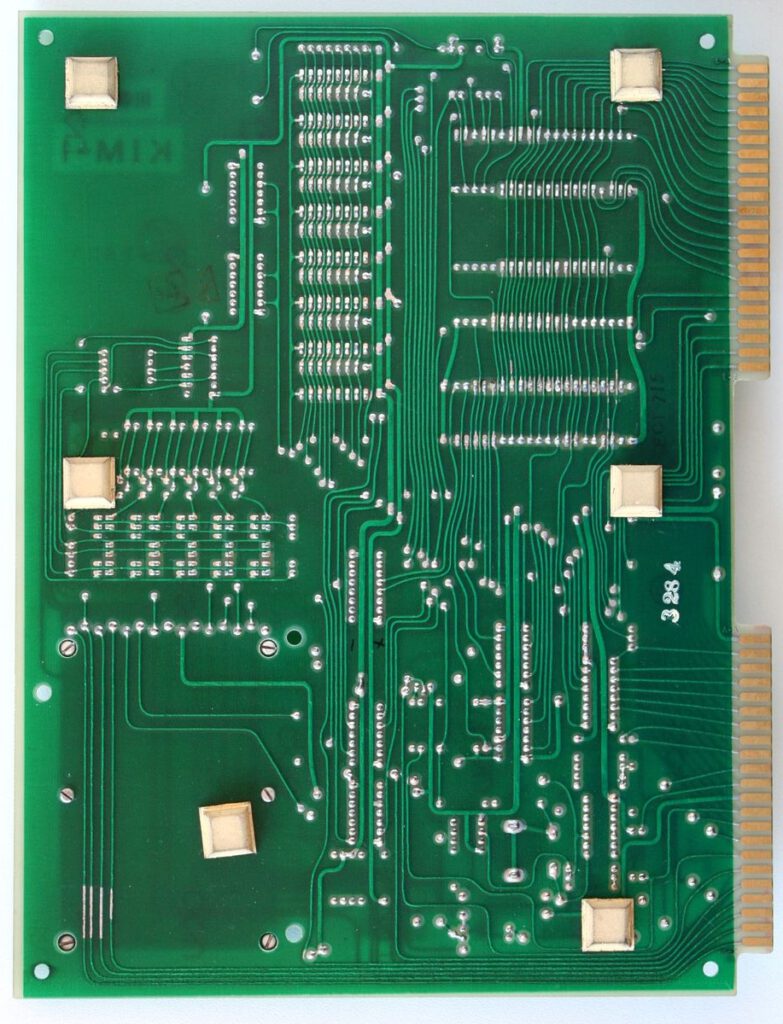

Rev A

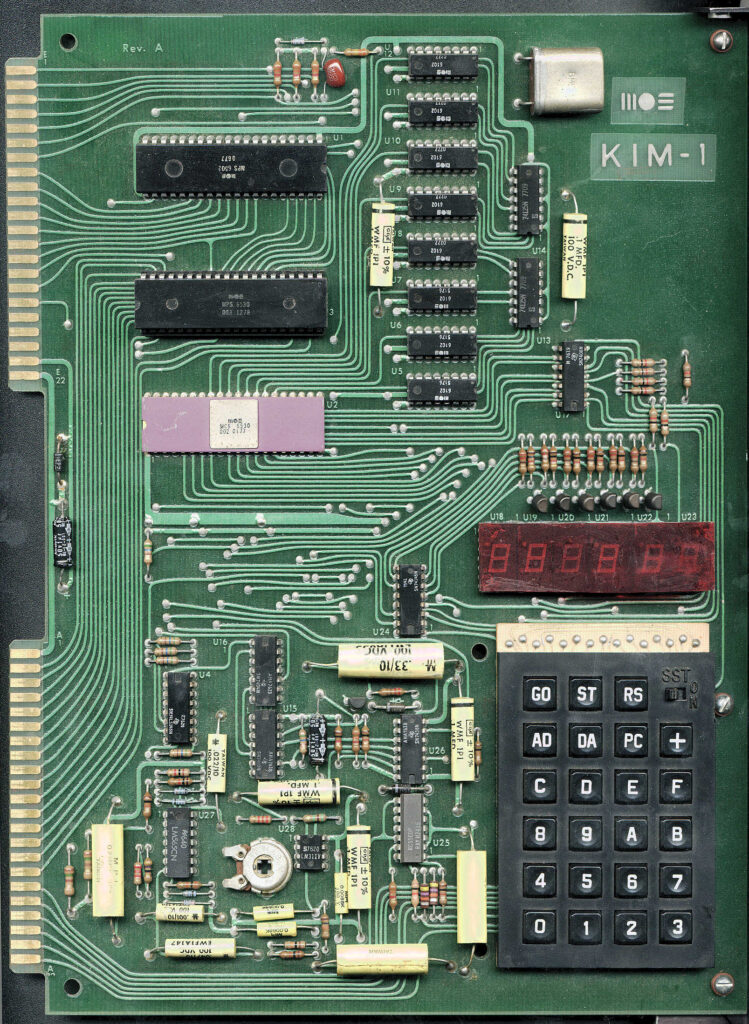

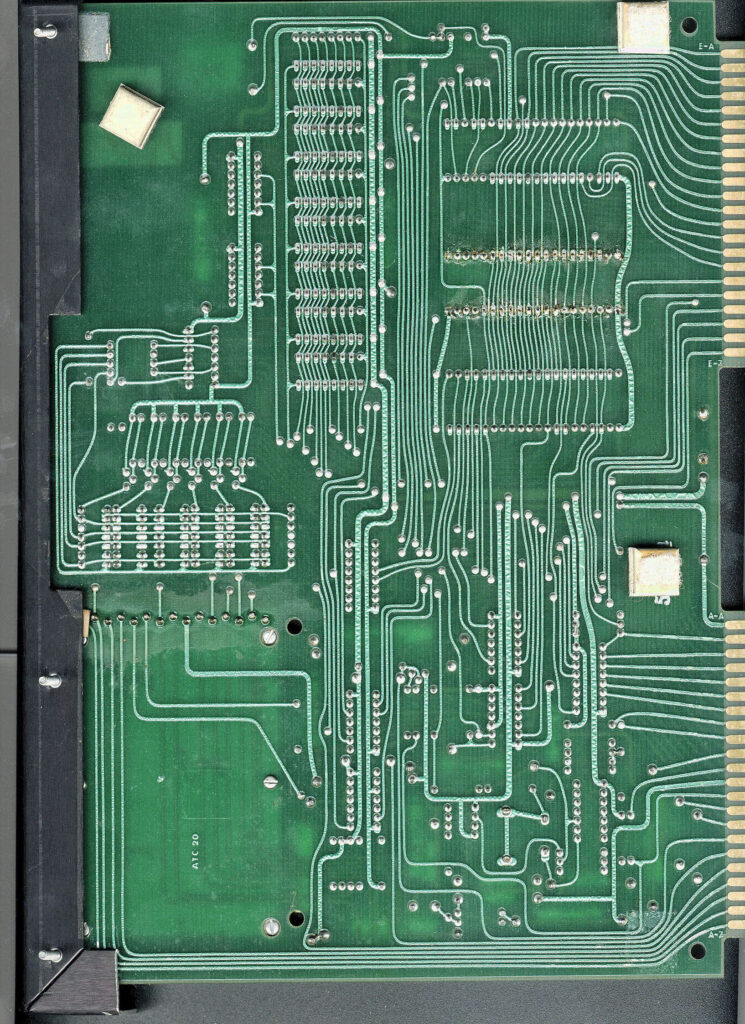

My Rev A CPU week 15 1976

My Rev A CPU week 15 1976

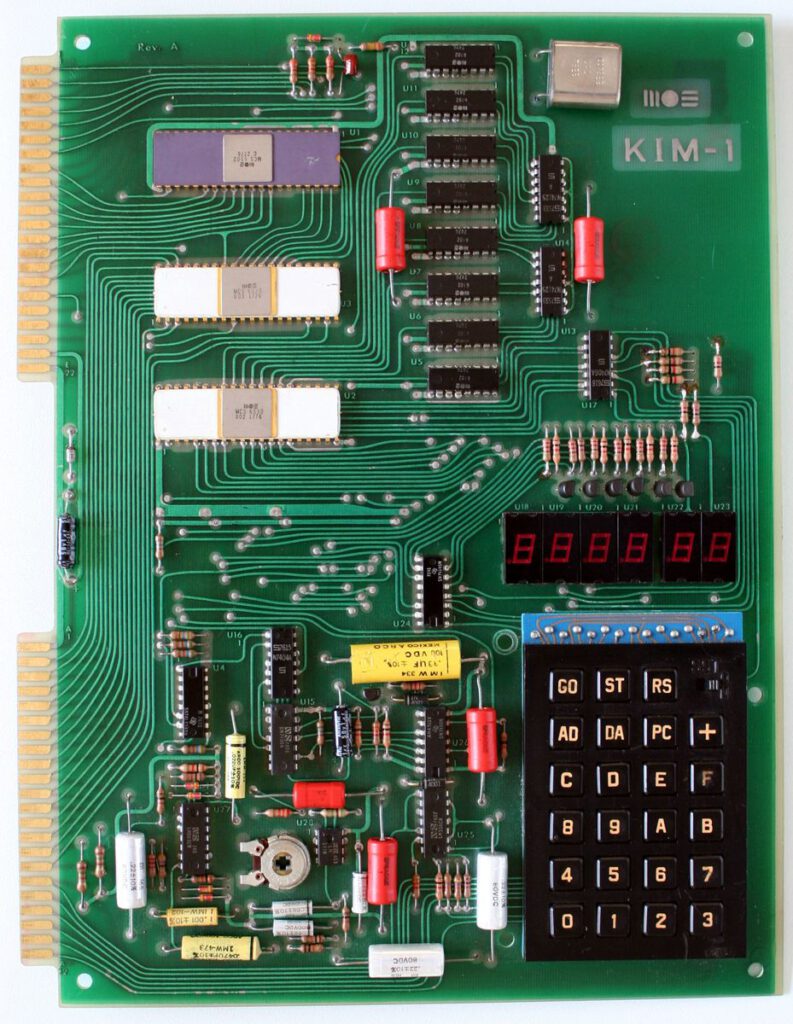

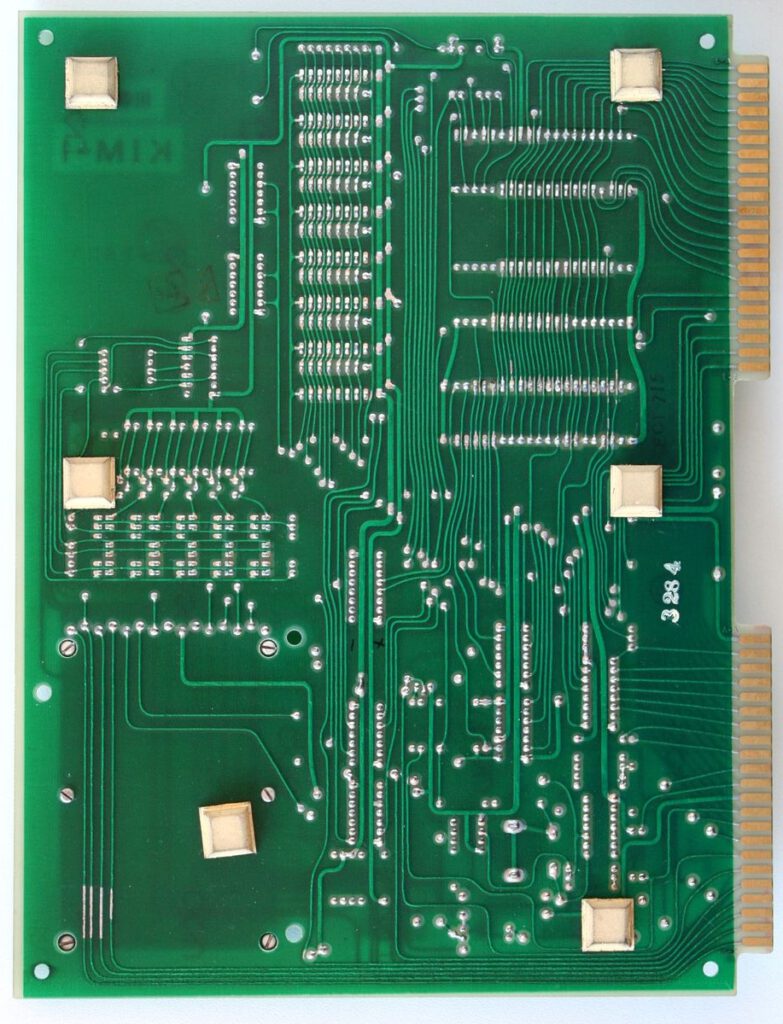

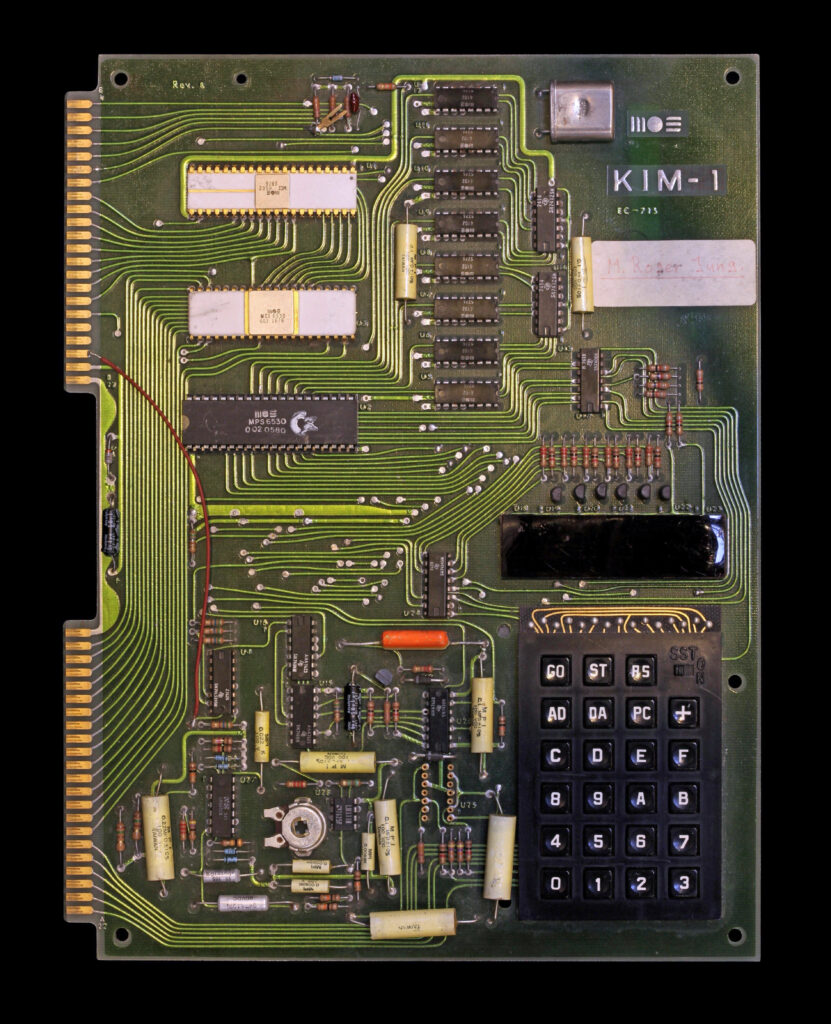

KIM-1 enthousiast

KIM-1 enthousiast

Rev A, photo by Guido Lehwalder

Rev A, photo by Guido Lehwalder

Rev B

Rev C

None found!

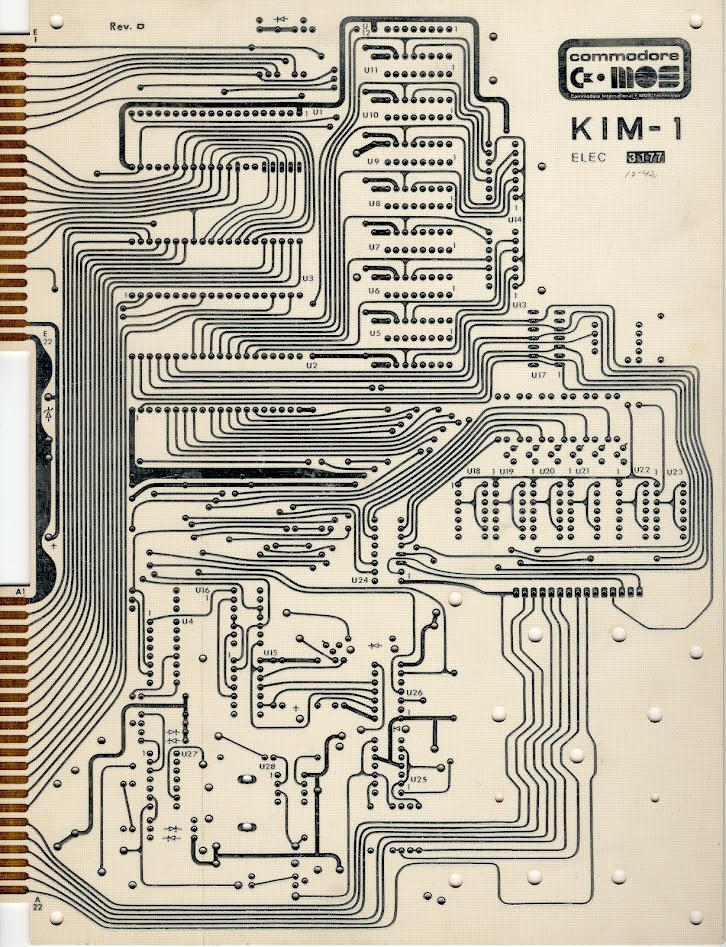

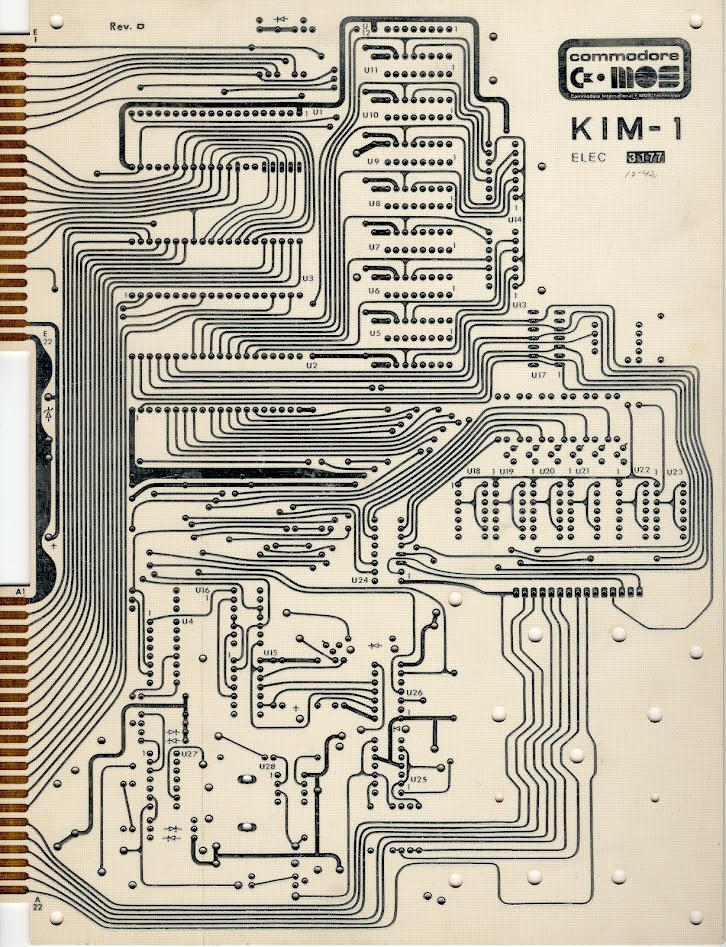

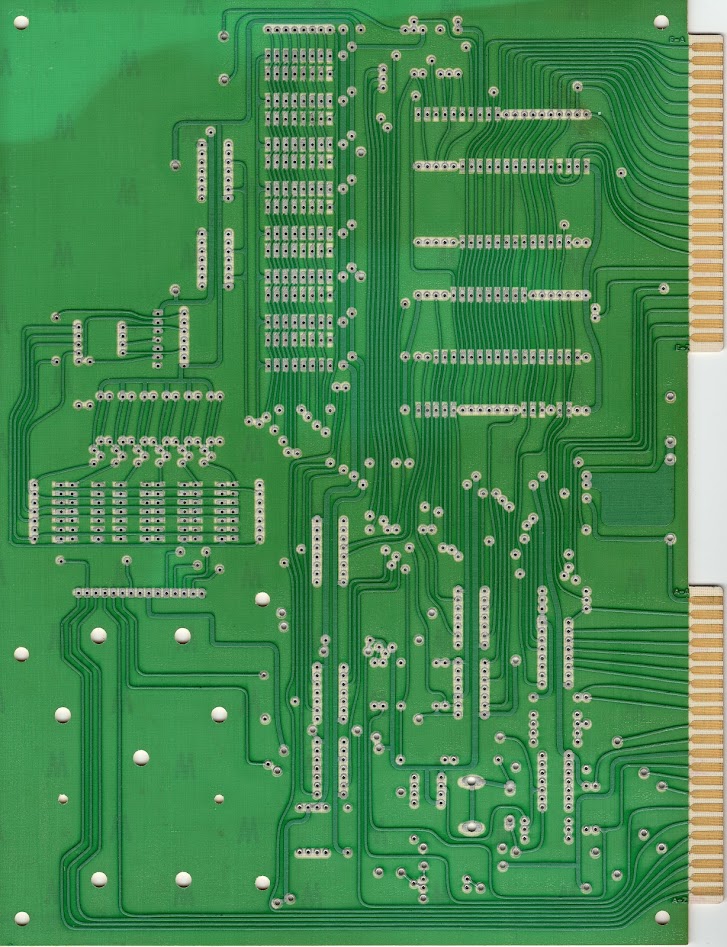

Rev D

Chuck Hutchins

Chuck Hutchins

Chuck Hutchins

Dave Dunfield

Dave Dunfield

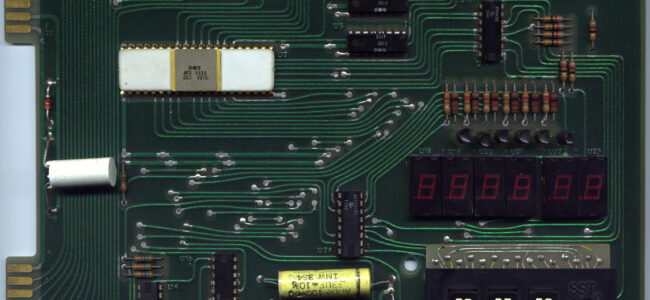

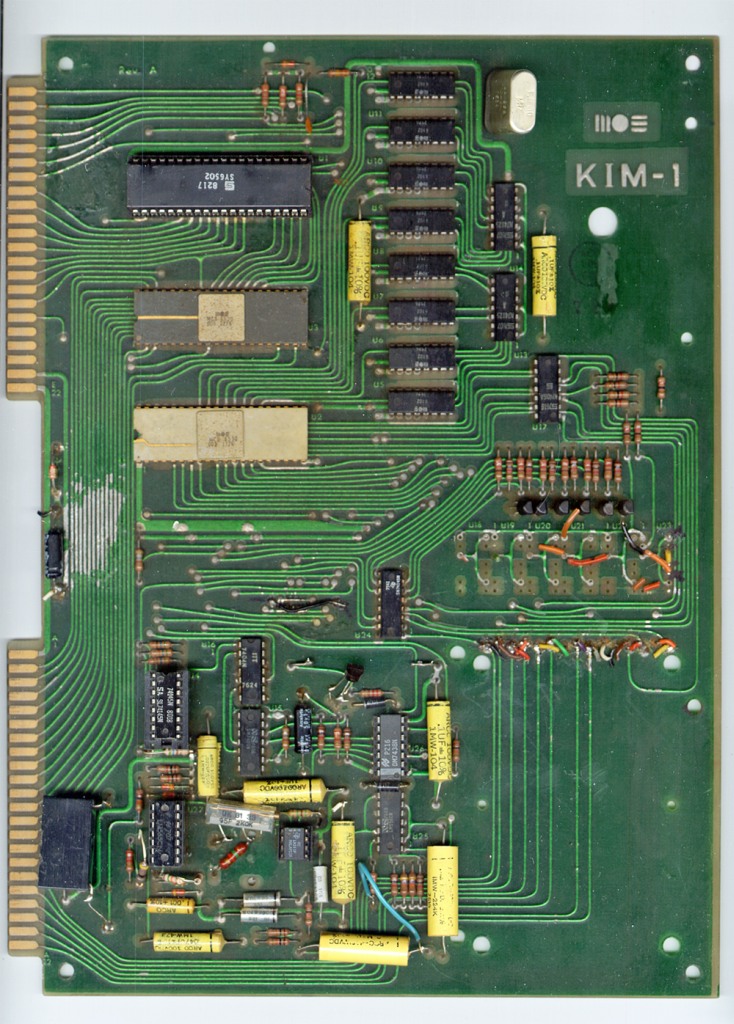

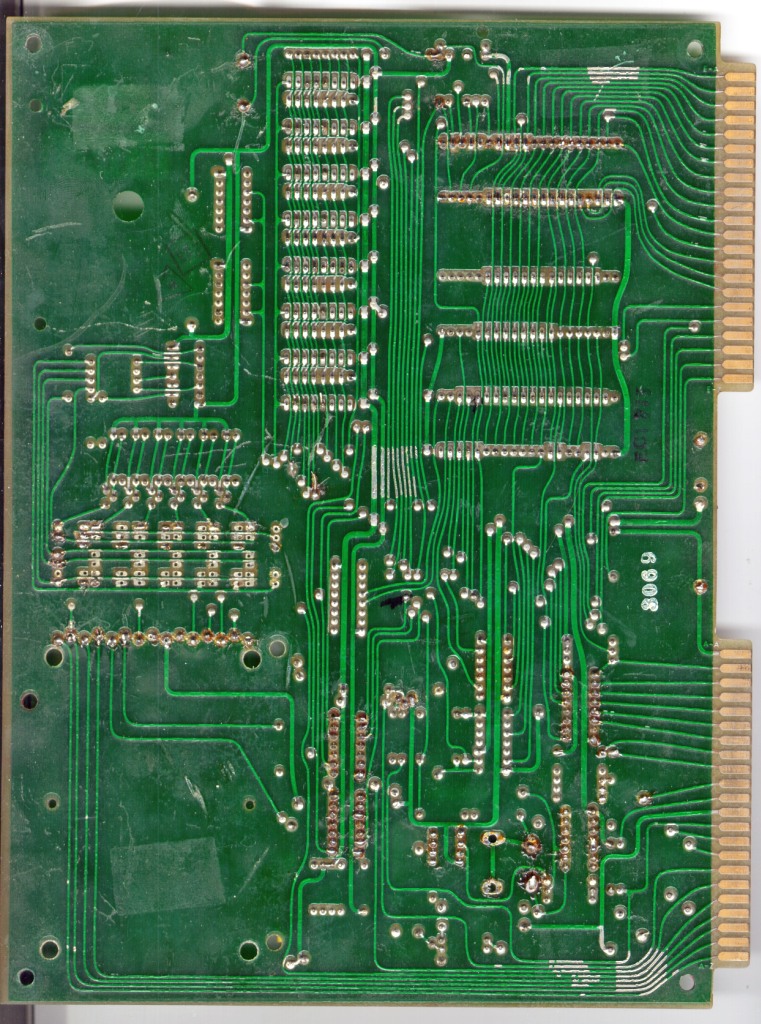

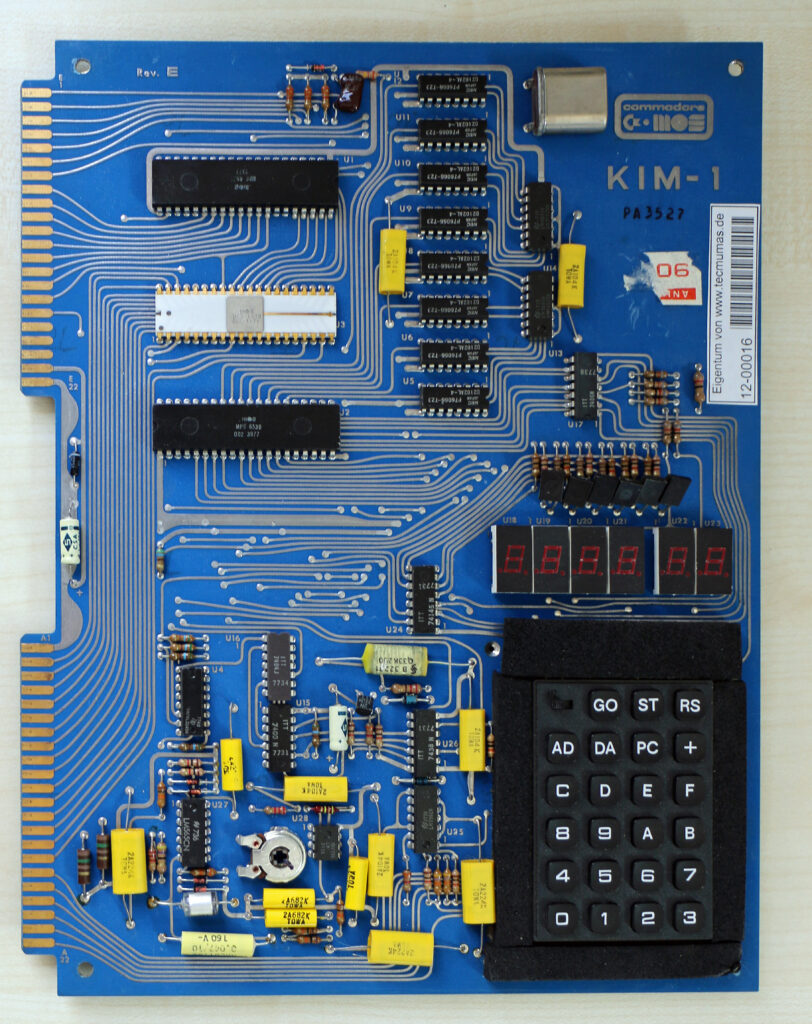

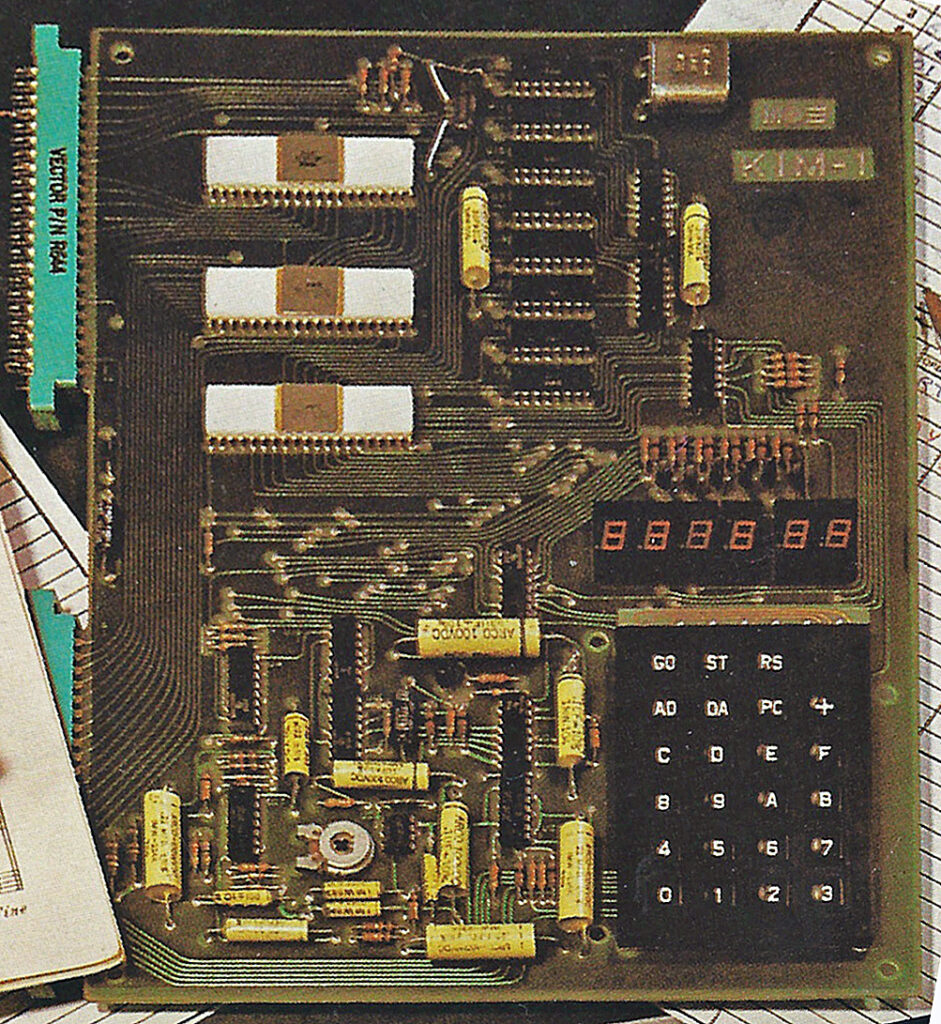

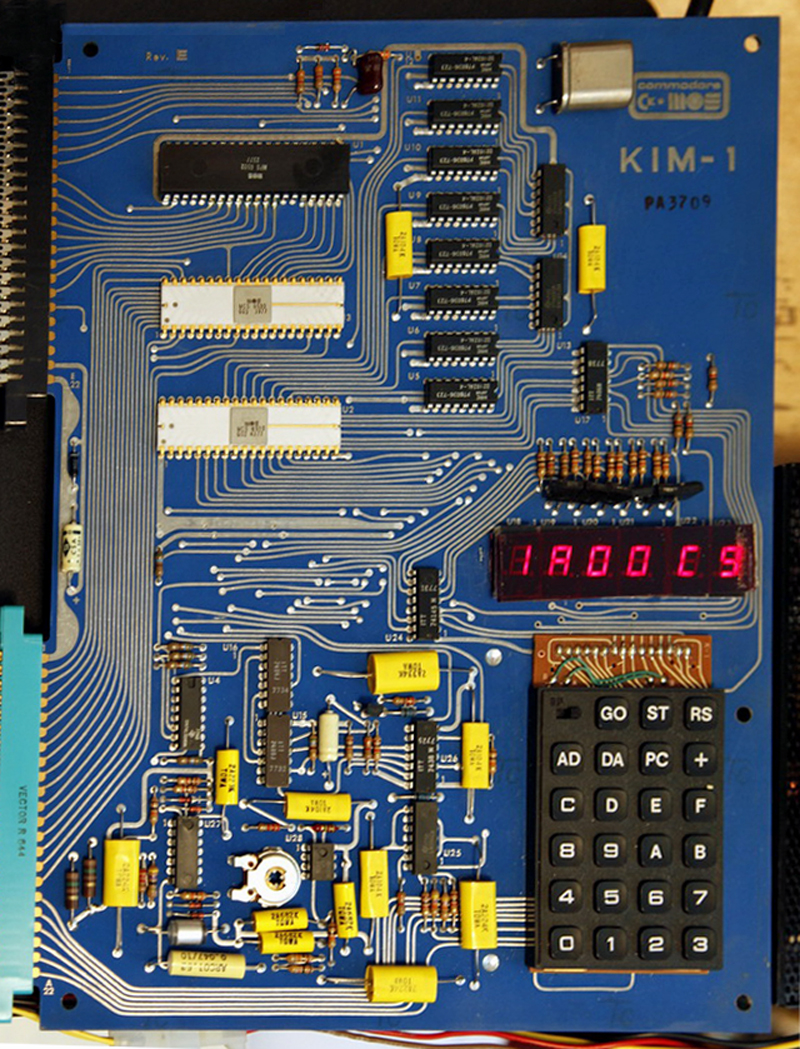

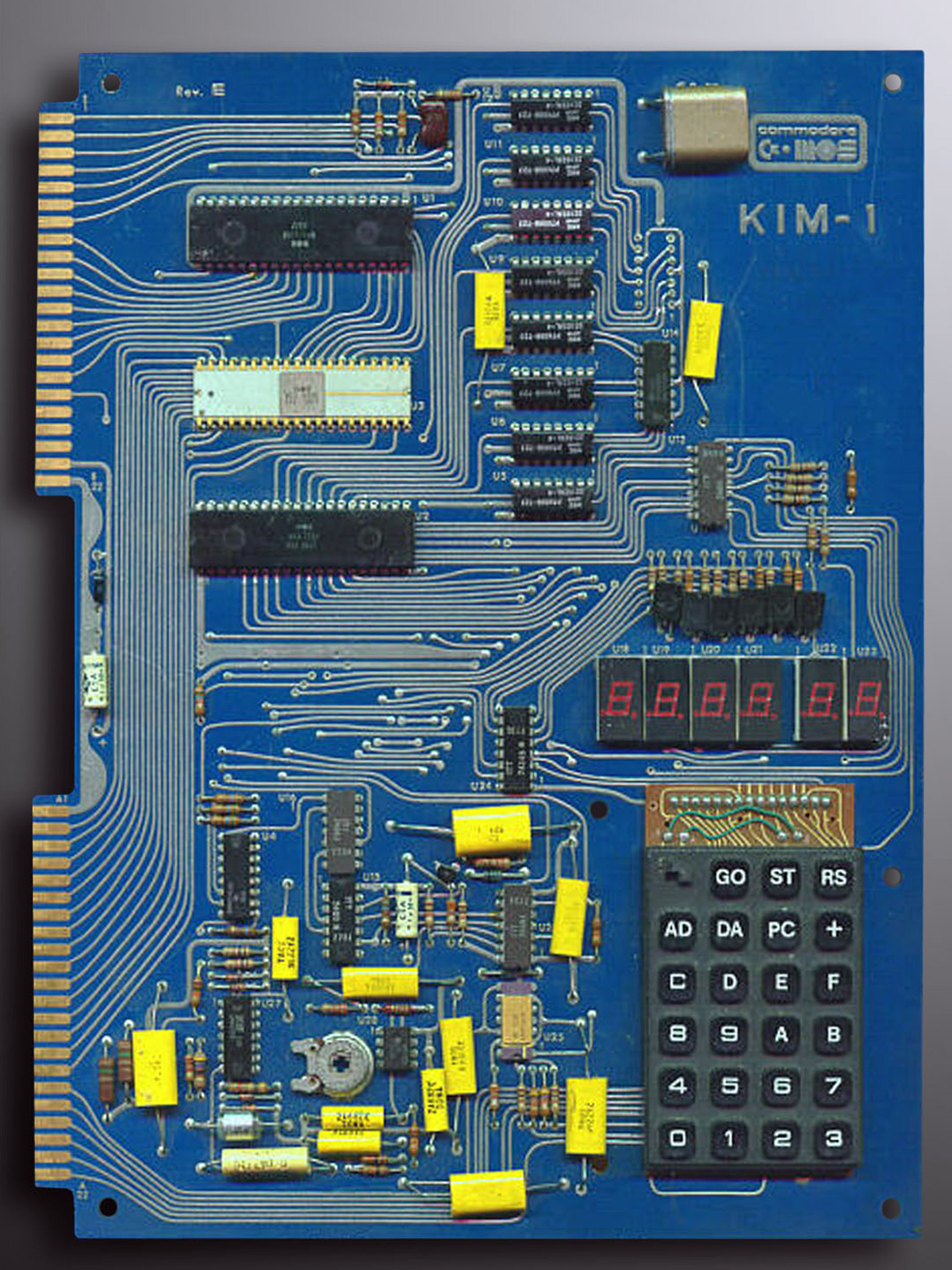

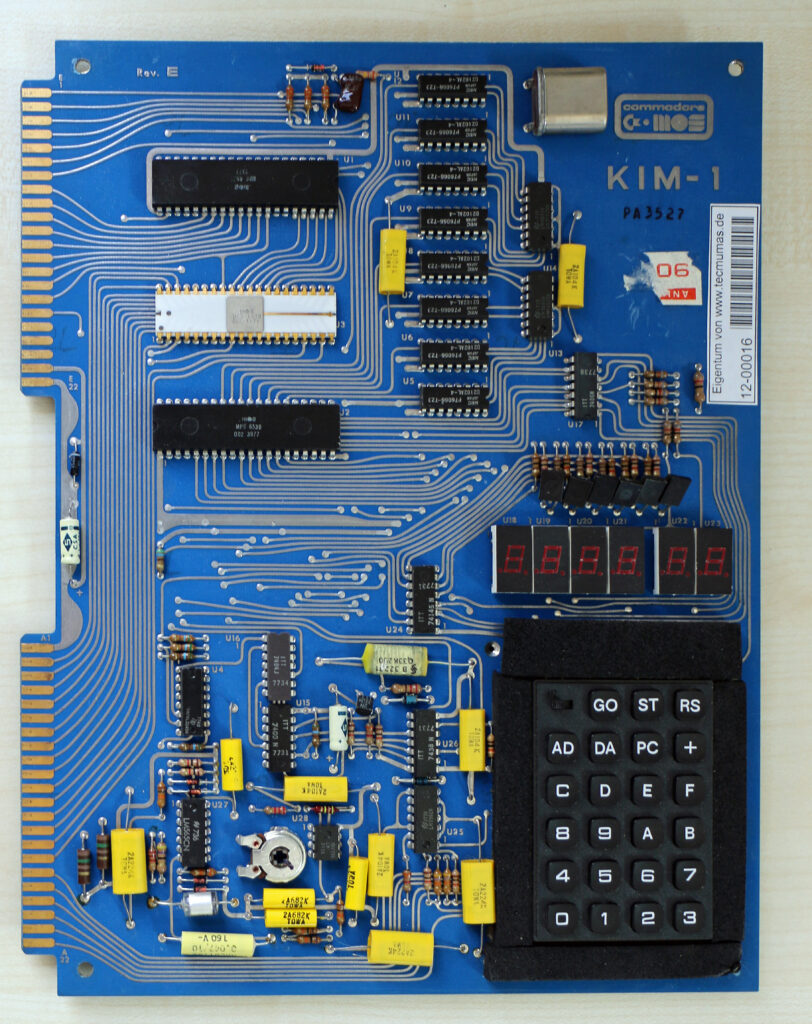

Rev E

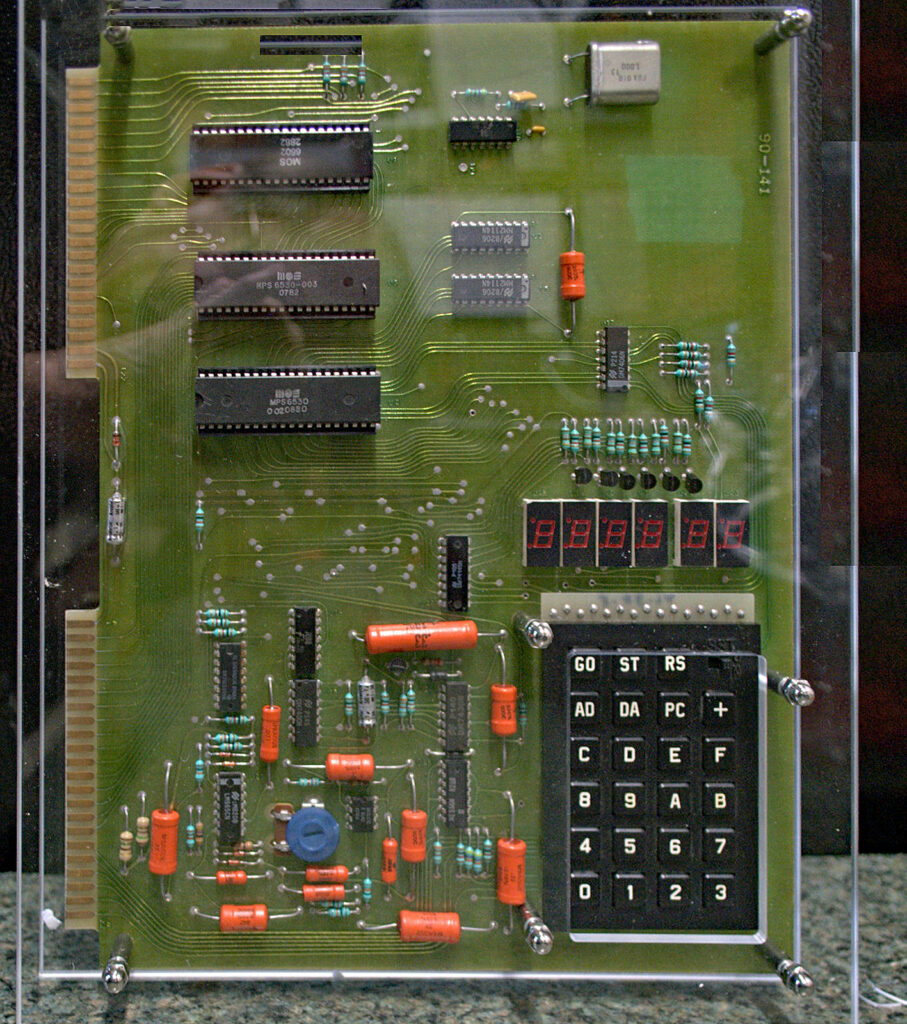

Stephan Slabihoud

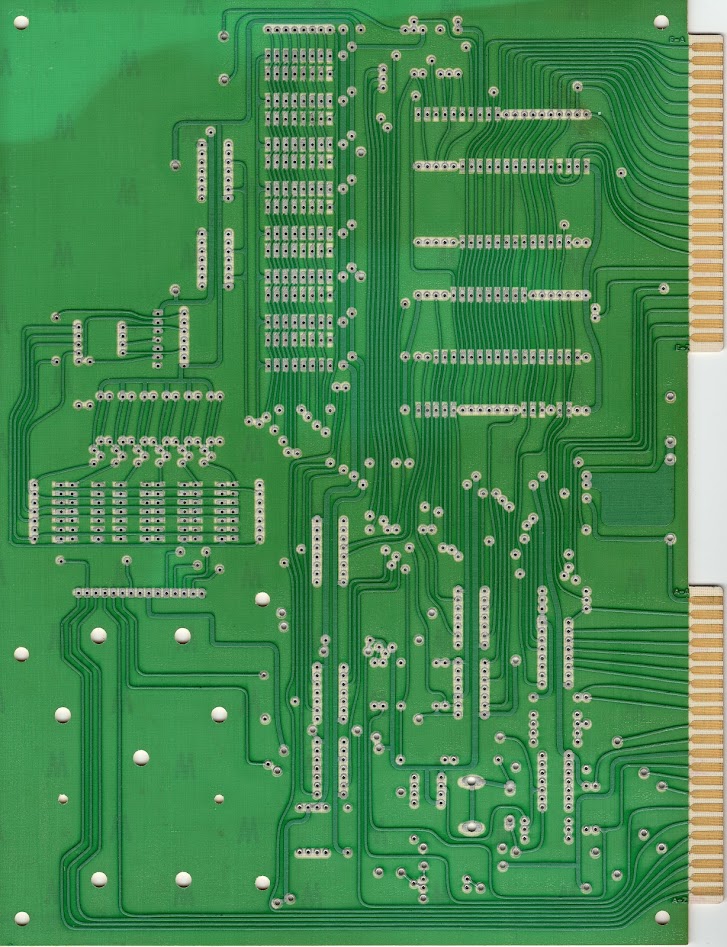

Photo made in TECMUMAS museum

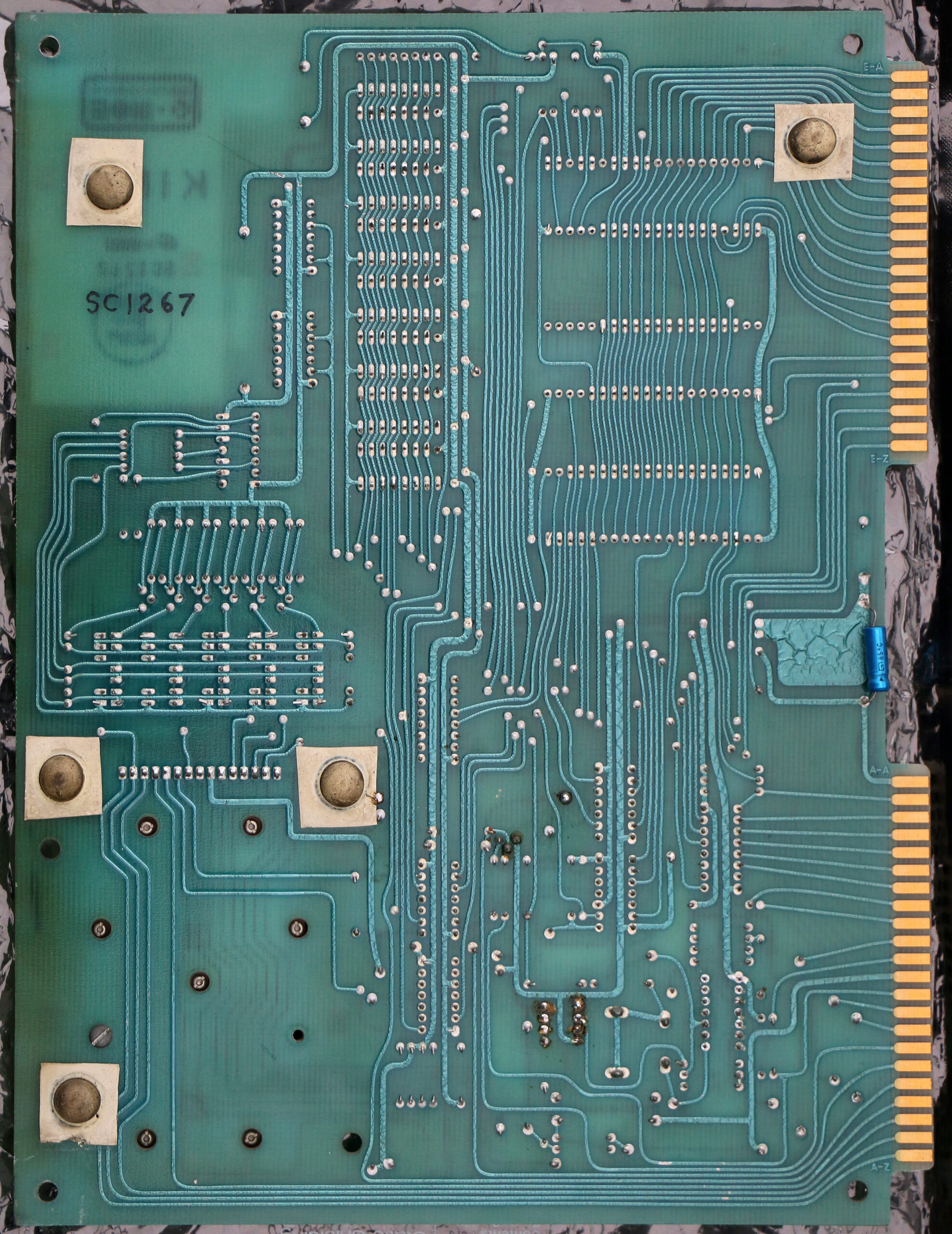

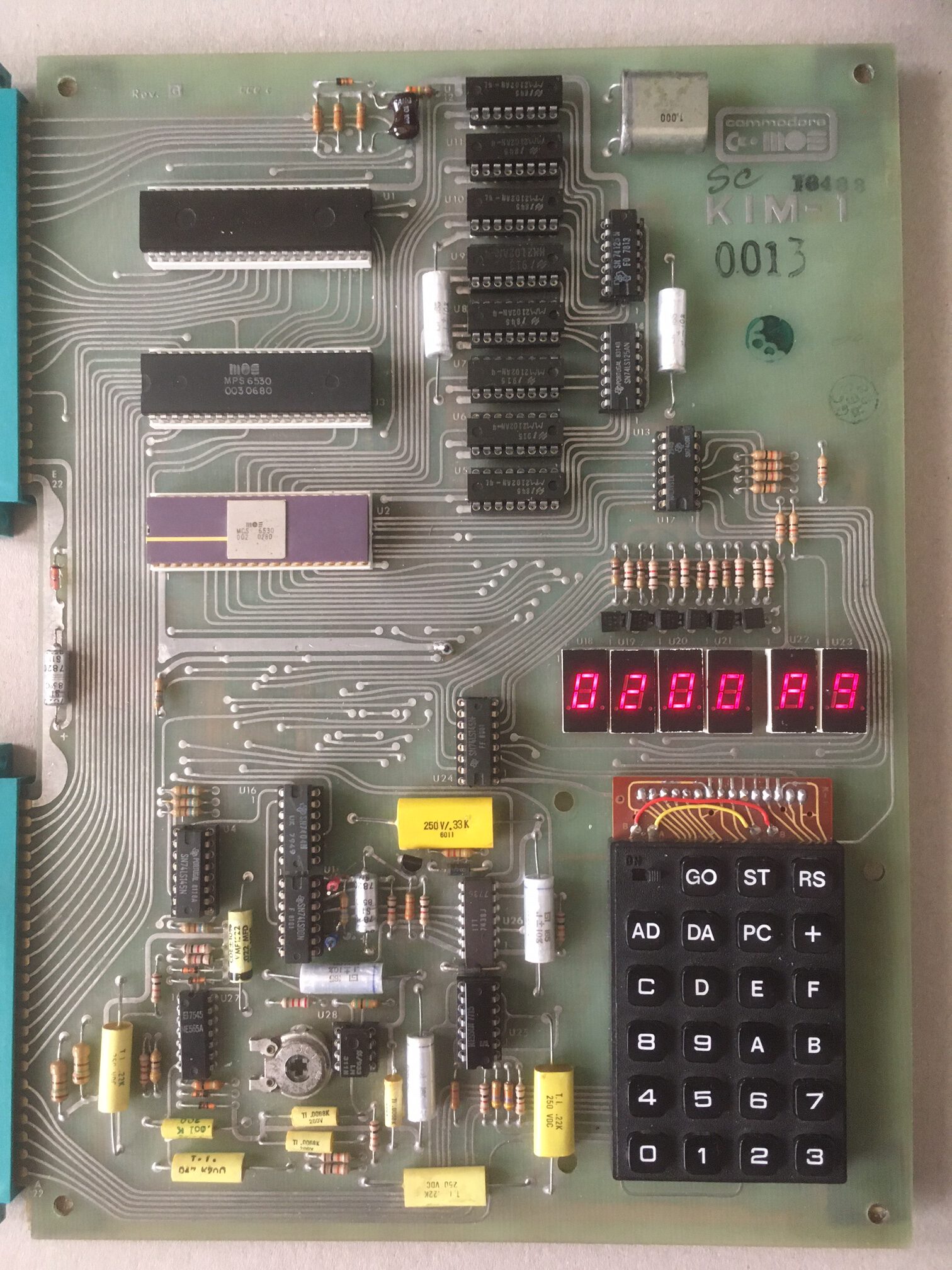

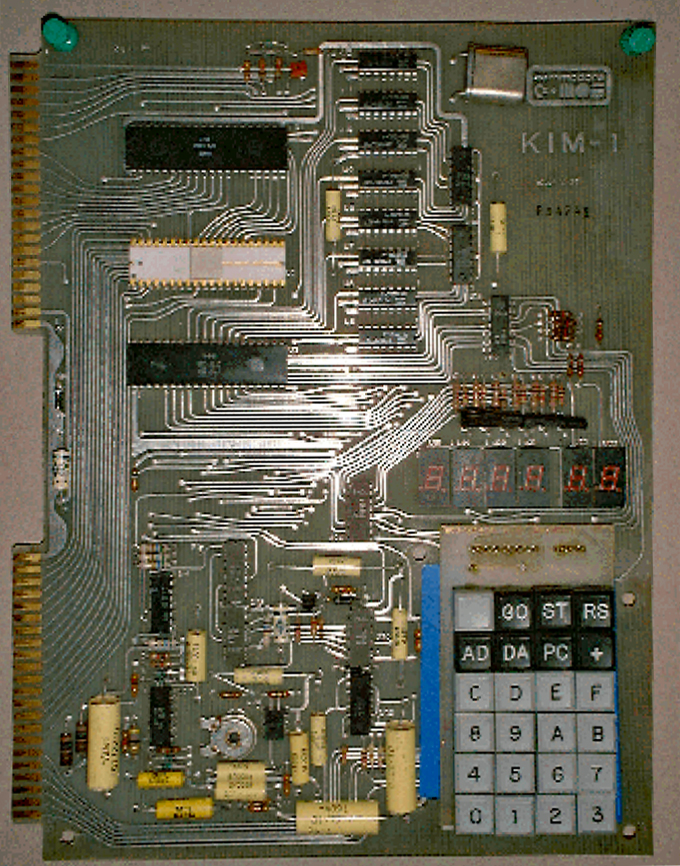

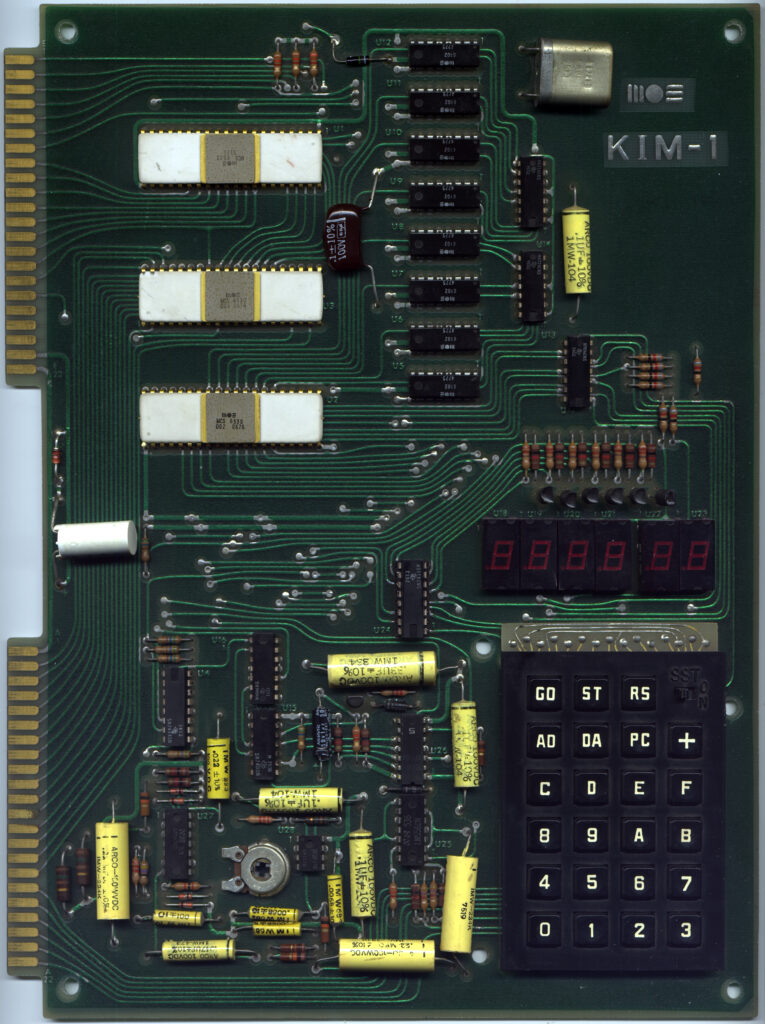

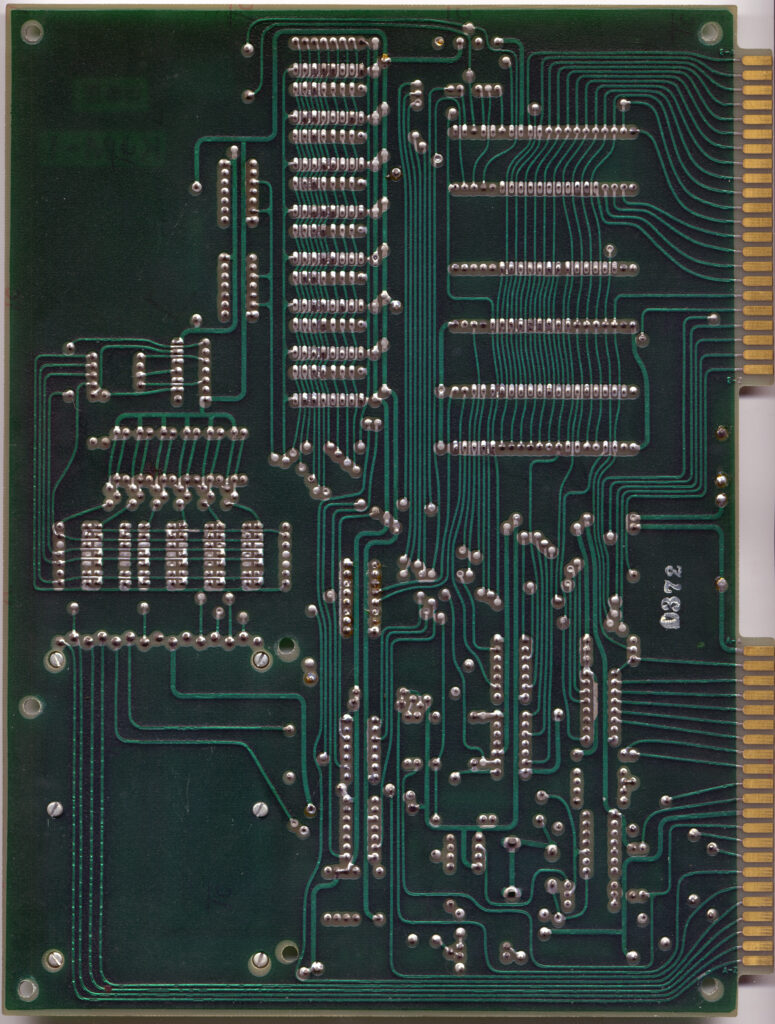

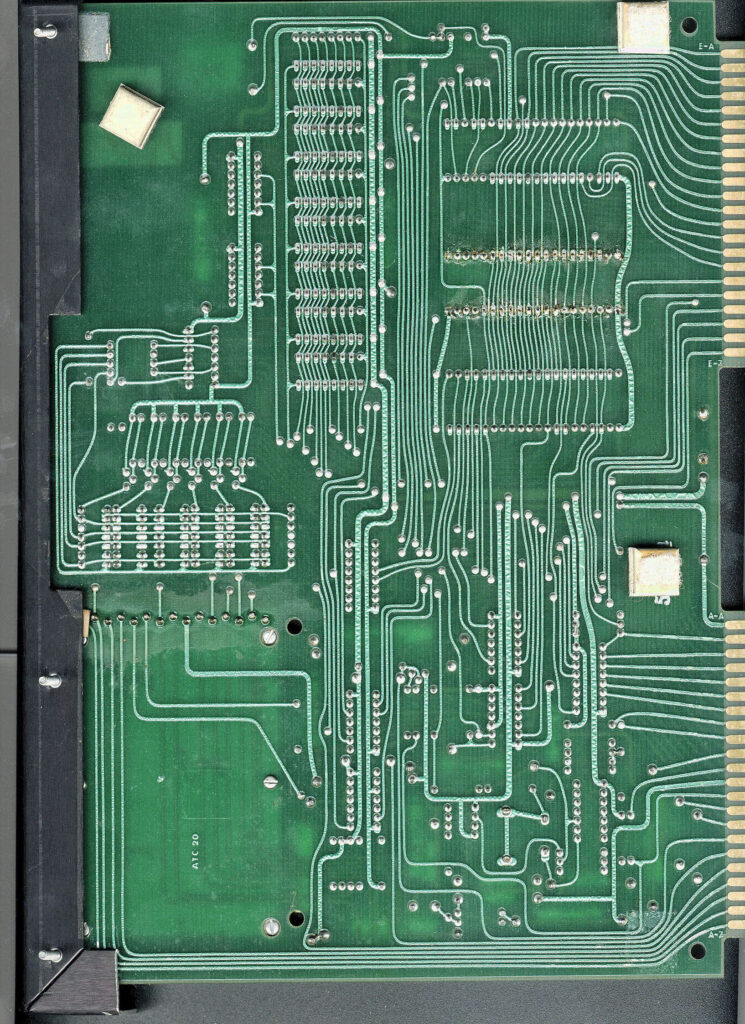

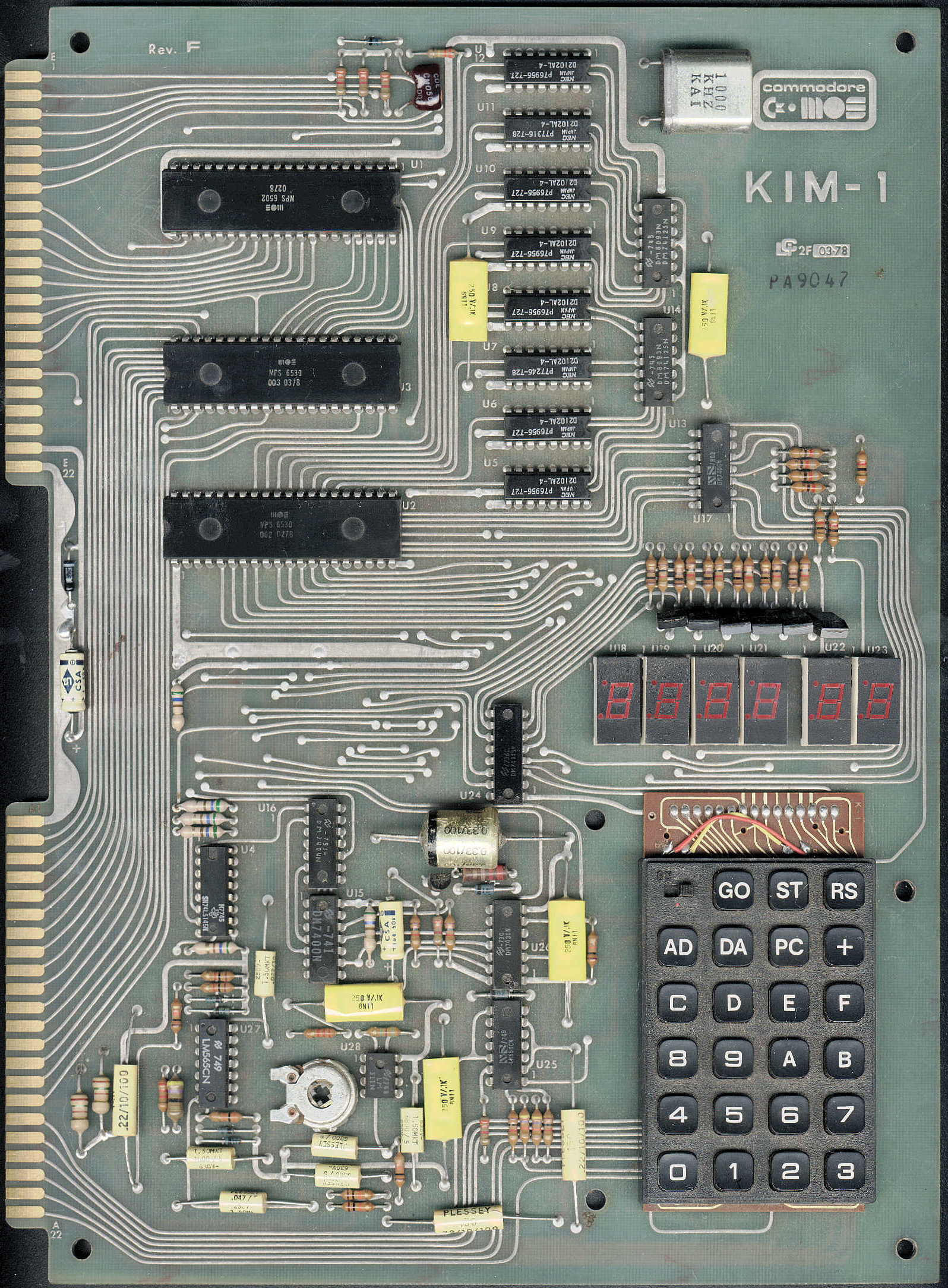

My original KIM-1

My original KIM-1

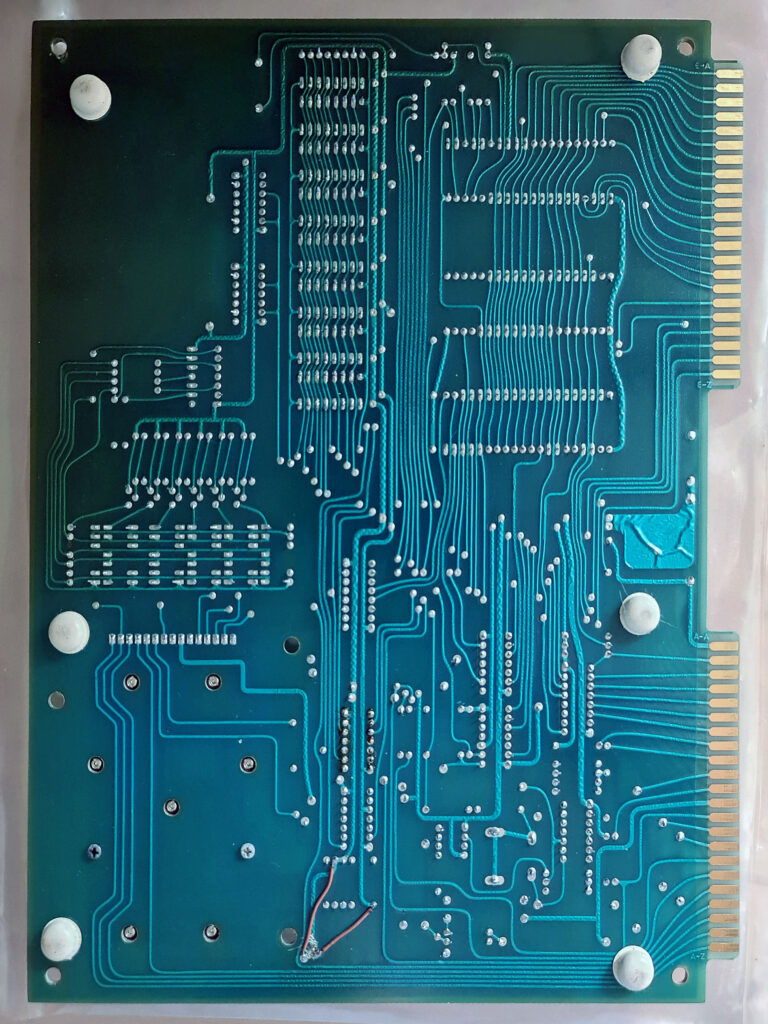

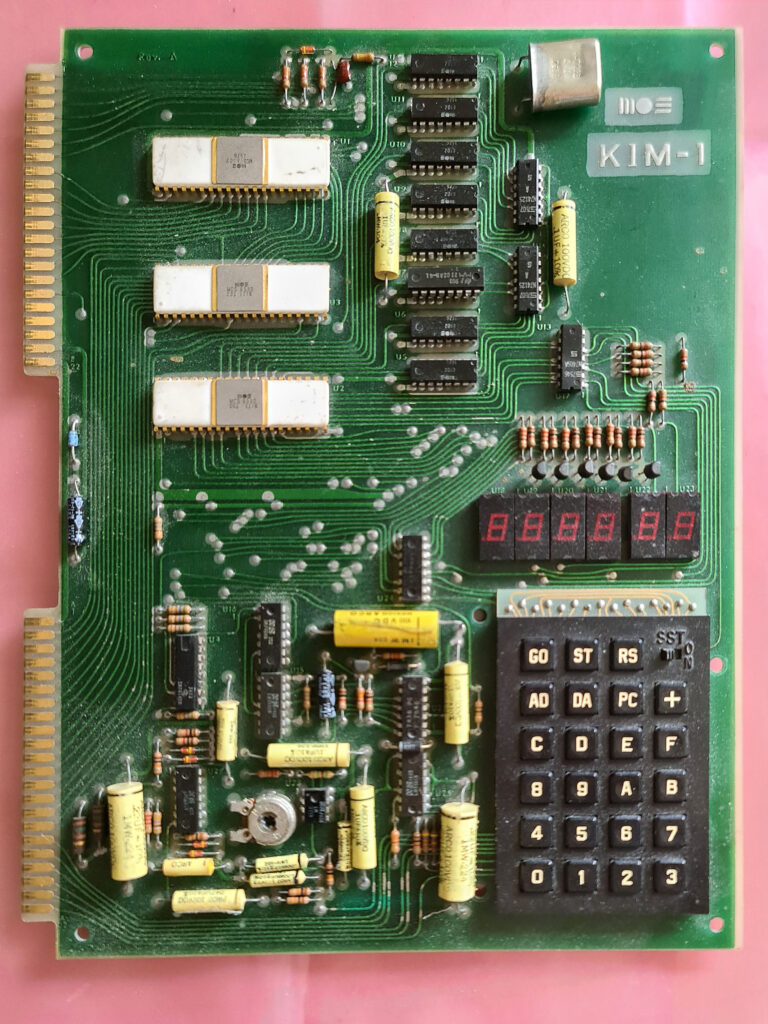

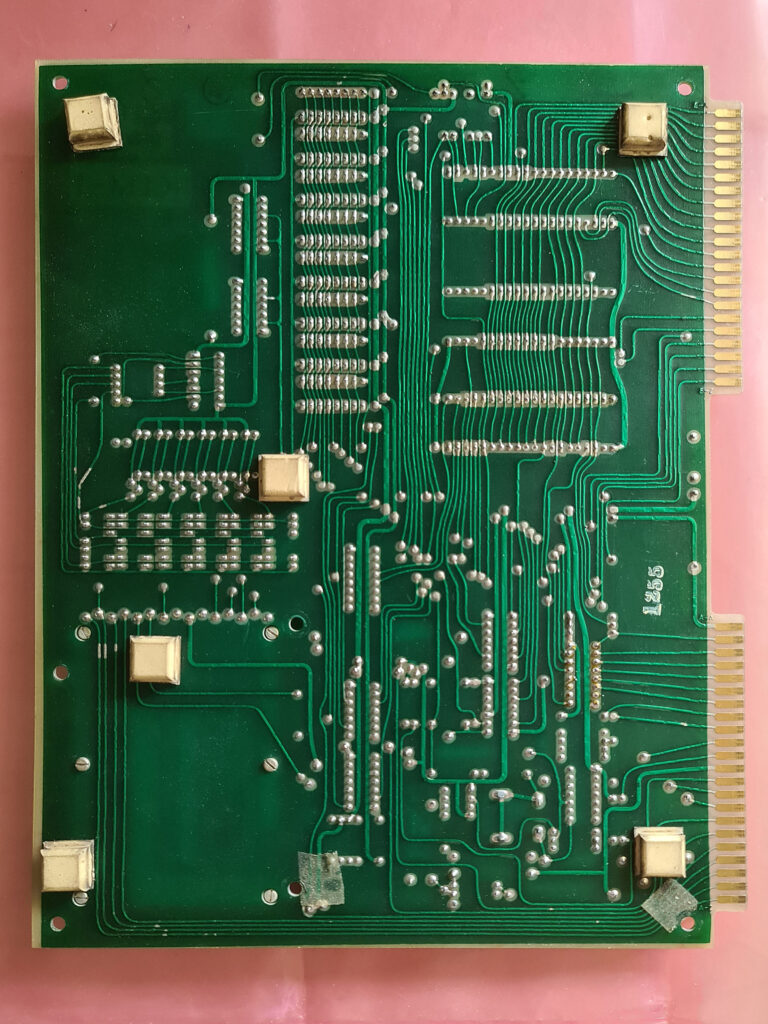

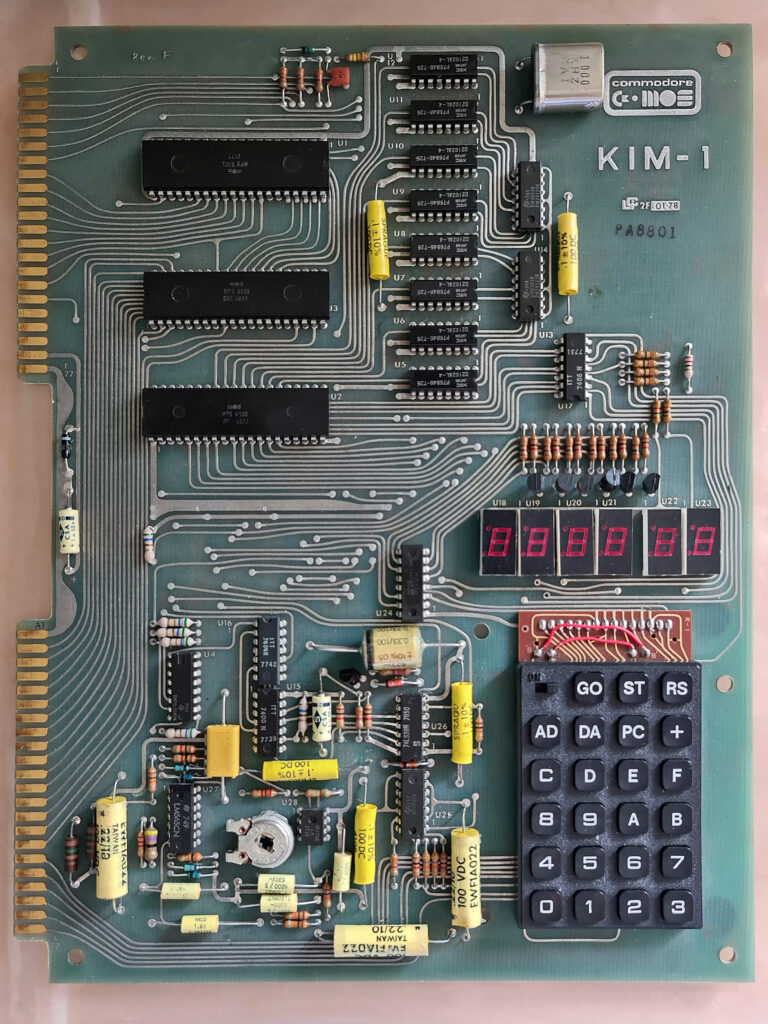

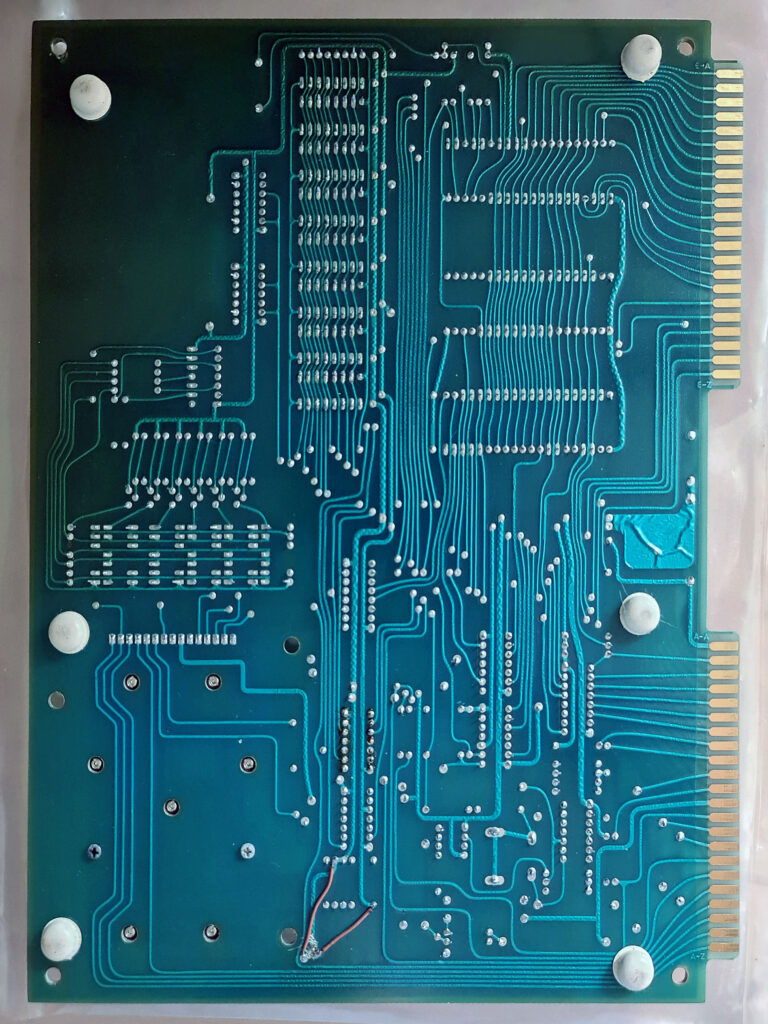

My second Rev F

My second Rev F

KIM-1 enthousiast

KIM-1 enthousiast

From HomeComputerMuseum.nl

From HomeComputerMuseum.nl

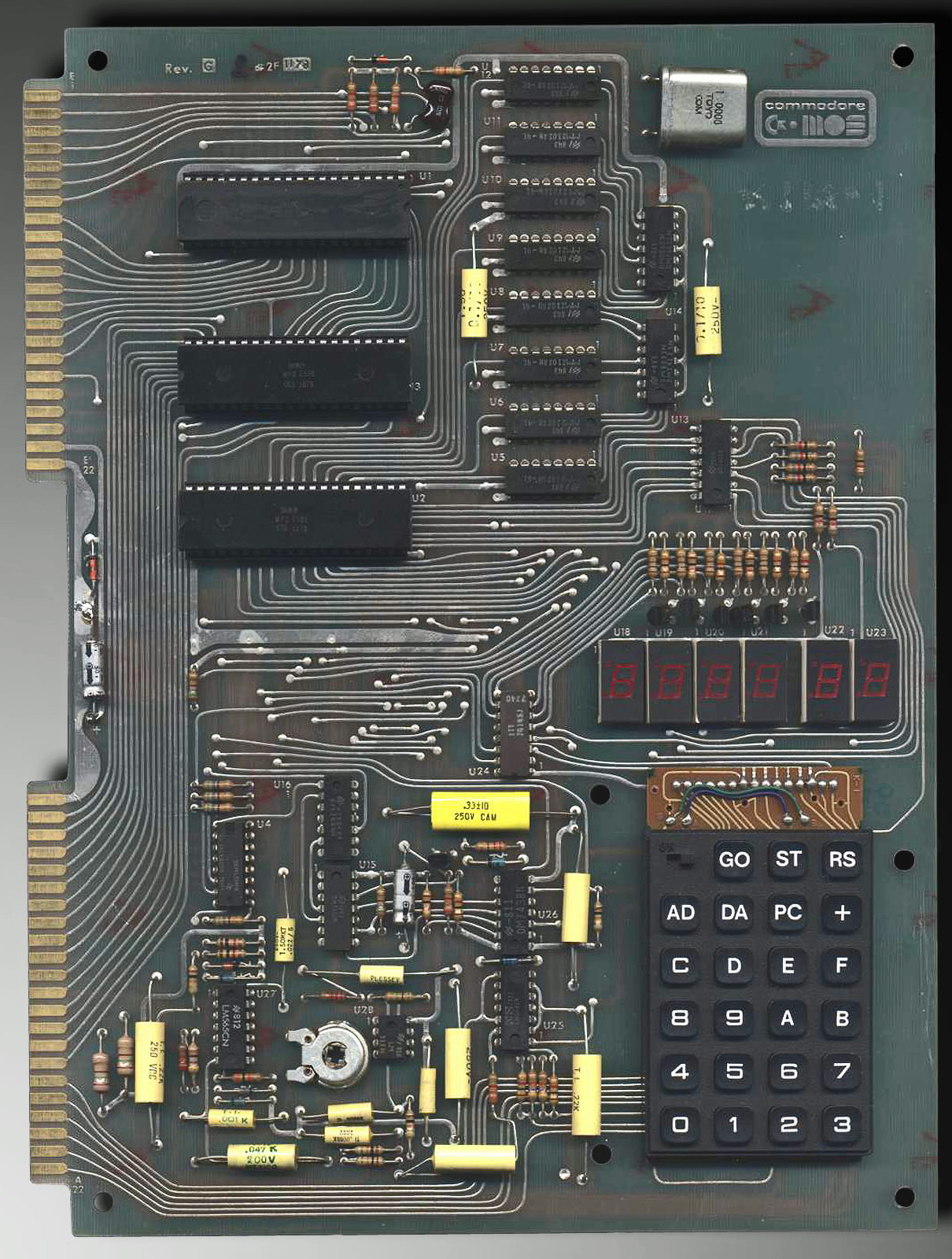

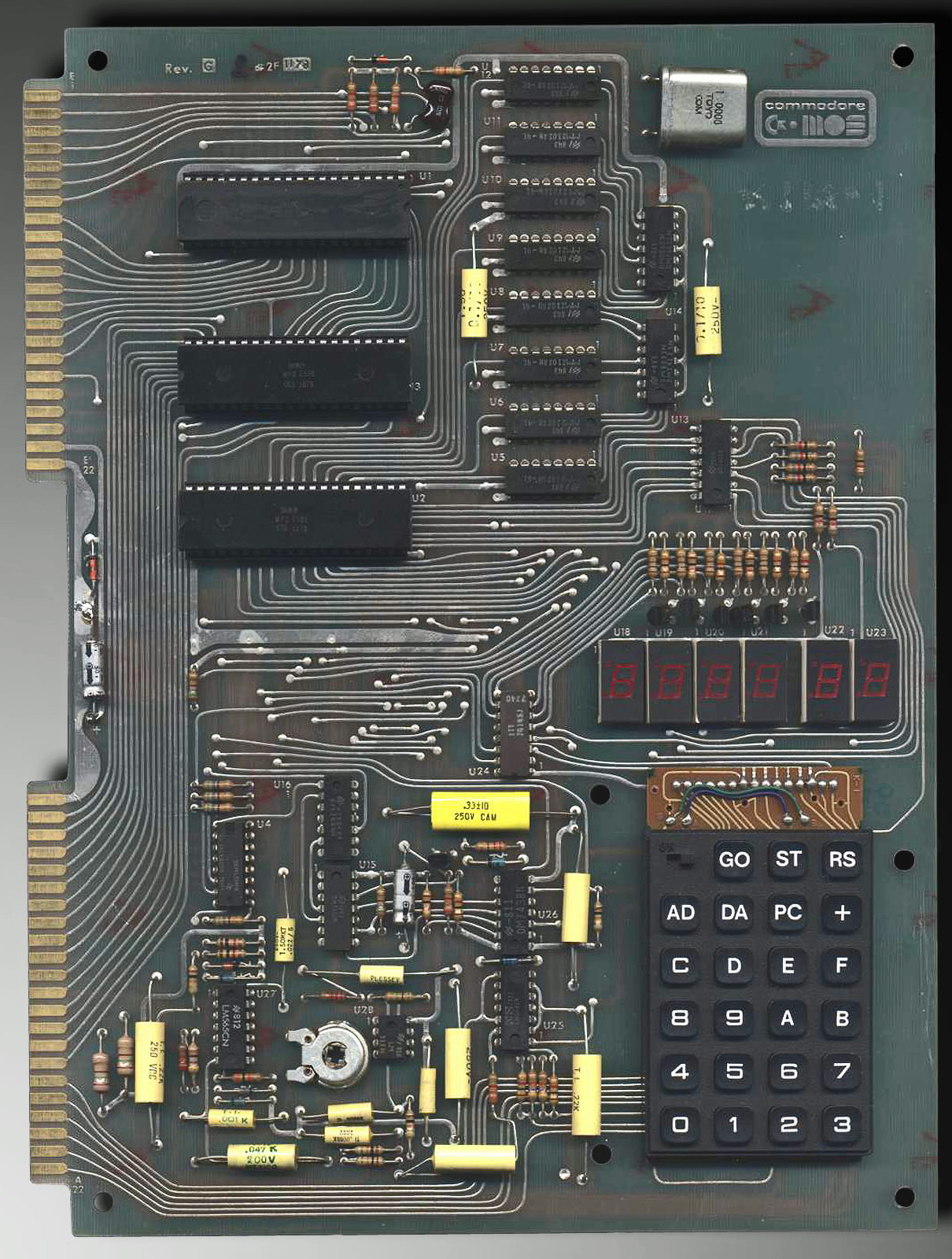

Rev G

Stephan Slabihoud

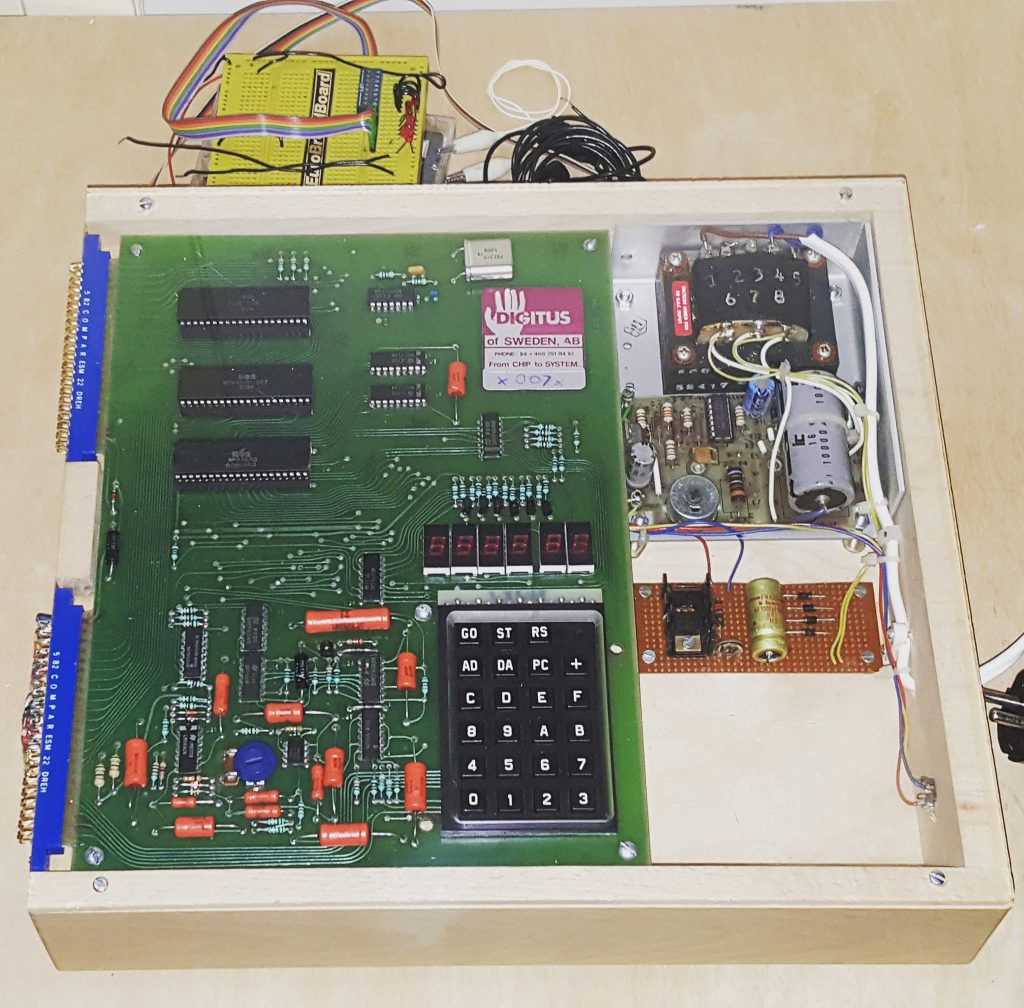

Dick Dral